Abstract:

Necrotizing fasciitis is a necrotizing soft tissue infection that can result in fast tissue loss, necrosis, and potentially fatal acute sepsis. Diabetes, cancer, alcohol abuse, and chronic liver and renal disease are all risk factors for necrotizing fasciitis.

Clinical presentation:

A 70-year-old female was admitted with complaints of chronic right leg pain and swelling. She was a known diabetic, obese and non- ambulant. There was no prior history of trauma. Initially it was treated as cellulitis of the right calf but during admission, the swelling was seen ascending to the thigh with tenderness. Patient was subjected to duplex to rule out deep vein thrombosis, incidentally, multiple echogenic foci with dirty shadowing was noted in the subcutaneous plane in the thigh, obscuring the underlying structures. Patient was then subjected to CT and MRI.

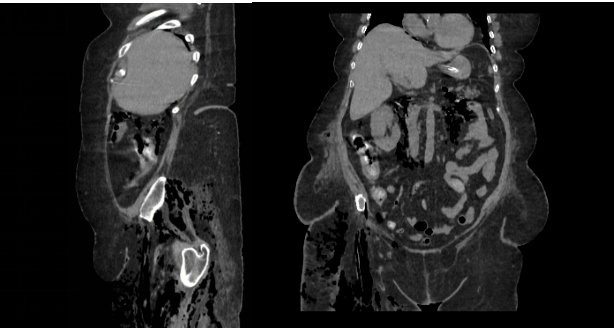

Imaging findings: CT abdomen sagittal and coronal views shows multiple air pockets in the subcutaneous as well as intramuscular plane in the right thigh and gluteal region. The air pockets are seen extending via the psoas and the paraspinal muscles to the other retroperitoneal spaces.

Imaging findings: Radiograph of right knee shows multiple radiolucenies seen in the subcutaneous and deep muscular plane. There is displaced fracture of the proximal shaft of tibia.

Imaging findings: Diffuse STIR hyper intensities with multiple hypointensities- suggestive of air pockets noted in the subcutaneous as well as intra/intermuscular plane in the gluteal region as well as thigh (predominantly anterior) extending upto the knee.

Discussion:

Necrotizing fasciitis is a fast-spreading and frequently fatal soft tissue infection that typically arises due to a polymicrobial infection. The infection starts in the superficial fascial planes and subsequently advances into the deep fascial layers, leading to necrosis through microvascular occlusion. The infectious agents responsible for this condition are typically a combination of aerobic and anaerobic organisms, including Clostridium species, Proteus species, Escherichia coli, Bacteroides species, Enterobactericeae species, and others. Necrotizing fasciitis is a medical emergency with a high mortality rate of 70-80%, with common causes of death being sepsis or respiratory, renal, or multisystem organ failure.

The Society of Infectious Disease categorizes necrotizing fasciitis into two types based on bacteriology profile: Type I and Type II. Type I is characterized by a mixed infection with both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, and is frequently observed in patients with underlying medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, alcoholism, malignancy (particularly leukaemia and lymphoma), immunocompromised, and post-surgical status (especially transplantations). Fournier gangrene, which refers to necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum, typically falls under Type I. On the other hand, Type II necrotizing fasciitis is caused by either group A Streptococcus (GAS, S. pyogenes) or Staphylococcus aureus, leading to gangrenous myofascitis with the potential complication of toxic shock syndrome, primarily due to the release of exotoxins A, B, and C. A crucial molecular virulent factor in GAS organisms is M-protein, which has antiphagocytic properties that enable the bacteria to evade the immune system’s defenses.

Clinical findings of necrotizing fasciitis include patchy skin discoloration, severe pain, and ill-defined swelling. Imaging, such as MRI, CT, and ultrasound, plays a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis and assessing the extent of the infection. Gas within the necrotized fasciae is a characteristic finding, but it may not always be present. Early diagnosis and aggressive surgical treatment are essential to reduce mortality, as the condition can be fatal if not promptly recognized and treated. Imaging findings, such as asymmetric thickening of fascia, soft tissue air, and blurring of fascial planes, help differentiate necrotizing fasciitis from other soft-tissue infections. The presence of soft-tissue gas, although specific, is not always present in all cases. Understanding the clinical and imaging features of necrotizing fasciitis is crucial for accurate and timely intervention to improve patient outcomes.

X- Ray is non- specific in early stages, but in latter stages shows multiple radiolucencies below the subcutaneous layer. Ultrasound appears to be more useful in children. Sonographic findings include distorted and thickened fascial planes with turbid fluid accumulation in the fascial layers and subcutaneous oedema. Soft tissue gas appears as a layer of echogenic foci with posterior dirty shadowing.

CT is the most commonly used imaging modality for evaluation of suspected necrotising fasciitis owing to its speed and sensitivity for gas in the soft tissues, which is present in <50% of cases. The sensitivity of CT is 80%, but the specificity is low given overlapping features with non-necrotising fasciitis. Gas within fluid collections tracking along fascial planes is the most specific finding. On contrast-enhanced CT, diffuse enhancement of fascia and/or underlying muscle can be seen but is present in both necrotising or non-necrotising fasciitis. On the other hand, absent enhancement of the thickened fascia suggests necrosis.

Liquefactive necrosis and inflammatory oedema both result in the accumulation of fluid in the fascial planes, which can be detected with MR imaging as increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images and variable intensity on T1-weighted images. This fluid accumulation is particularly noticeable in thickened deep fascial planes. Fat-suppressed T2-weighted imaging is generally better at displaying inflammatory changes than fat-suppressed gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted imaging. Gas bubbles, if present, appear as focal signal voids on both T1- and T2-weighted images. The subcutaneous tissues may show increased signal intensity, similar to cellulitis, but in contrast to cellulitis, the deep fascia is also involved in this condition.

References

- Donnelly L, Frush D, O’Hara S, Bissett G. Necrotizing fasciitis: an atypical cause of acute abdomen in an immunocompromised child. Pediatr Radiol 1998; 28:109–111.

- Becker M, Zbaren P, Hermans R, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis of the head and neck: role of CT in diagnosis and management. Radiology 1997; 202: 471–476.

- Callahan E, Adal K, Tomecki K. Cutaneous (non HIV) infections. Dermatol Clin 2000; 18:497– 508.

- Struk D, Munk P, Lee M, Ho S, Worsley D. Imaging of soft tissue infections. Radiol Clin North Am 2001; 39:277–301.

- Walshaw C, Deans H. CT findings in necrotizing fasciitis: a report of four cases. Clin Radiol 1996

Dr. Babu Peter Sathyanathan

Dr. Babu Peter Sathyanathan

Consultant Radiologist

Kauvery Hospital, Chennai

Dr. Rupini.S

Dr. Rupini.S

Senior Resident in Radiology

Kauvery Hospital, Chennai

Dr. Deepan

Dr. Deepan

Post Graduate Resident – Radiology

Kauvery Hospital, Chennai