CASE HISTORY

Mrs. X, a 63-year-old female, presented to the emergency department with high-colored urine for five days, yellowish discoloration of the skin and eyes for two days, and shortness of breath for one day. She reported a history of fever two weeks prior, lasting two days without localizing signs, which resolved spontaneously. She denied symptoms of fever, hematuria, dysuria, increased urinary frequency, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, visual disturbances, headache, cough, chest pain, palpitations, weight loss, loss of appetite, evening fever, or oral ulcers. She gives history of Menopause by age 47 with no history of abnormal uterine bleeding. She had no previous similar episodes or other comorbidities, apart from a total knee replacement one year ago. Her diet was mixed, with normal bowel and bladder habits and adequate sleep. She performed her activities of daily living independently. There was no family history of similar complaints or recent drug intake. Mrs. X belongs to an upper- middle-class family.

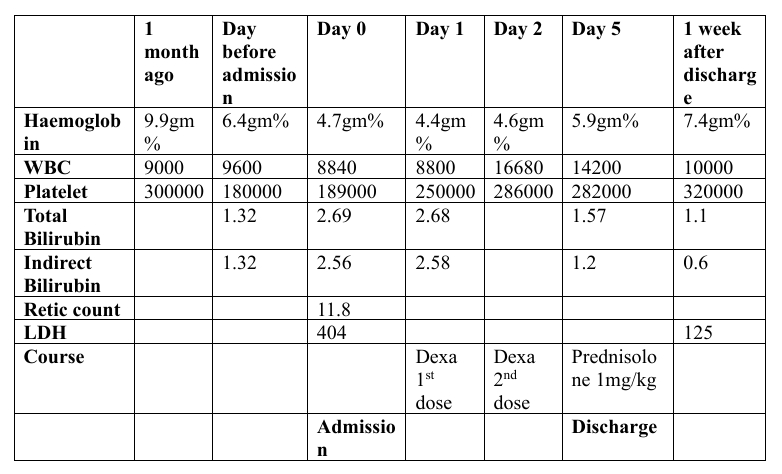

Initial investigations ordered by her first consulting doctor revealed hemoglobin of 6.1 g/dL, MCV of 60.2 fL, MCH of 18.4 pg, WBC count of 9,600/μL, LDH of 375 U/L, total bilirubin of 2.92 mg/dL, and indirect bilirubin of 1.32 mg/dL. A normal abdominal ultrasound was also reported. She was referred for further management.

ON EXAMINATION

On examination, Mrs. X was moderately built and nourished, conscious, oriented, and afebrile, with significant pallor and icterus but no clubbing, lymphadenopathy, or pedal edema. Her systemic examination was normal. Echocardiography showed an ejection fraction of 60%, mild tricuspid regurgitation, and Grade 1 mitral regurgitation.

INVESTIGATIONS

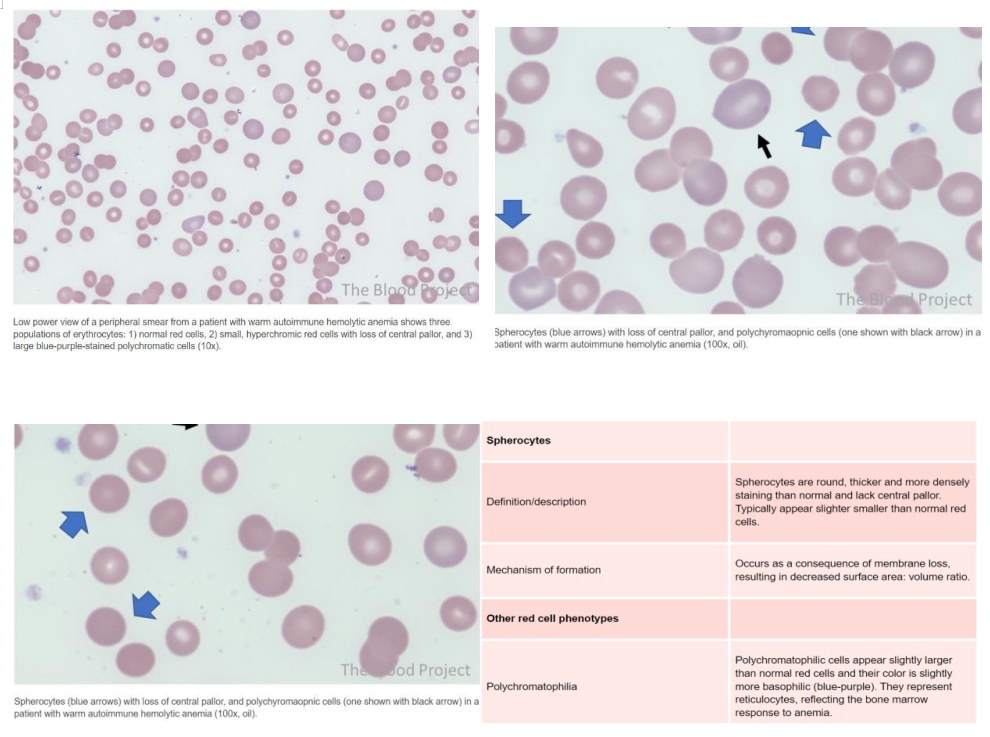

Upon admission, initial blood investigations showed hemoglobin of 4.7 g/dL, WBC count of 8,840/μL, platelet count of 180,000 /μL, LDH of 404 U/L, and total bilirubin of 2.64 mg/dL with predominance of indirect bilirubin. Peripheral smear indicated anemia with anisocytosis, numerous teardrop cells, stomatocytes, occasional fragmented cells, and polychromatophilic cells. Serum iron was 153 μg/dL, TIBC 277 μg/dL, ferritin 193 ng/mL, and vitamin B12 1,877 pg/mL. Reticulocyte count was elevated at 11.8%, suggesting hyperproliferative anemia indicative of hemolysis.

Further testing, including direct and indirect Coombs tests, returned positive. A bone marrow biopsy revealed hypercellular marrow with erythroid hyperplasia and no abnormal infiltrates. Additional investigations to determine the cause of hemolytic anemia included a normal CT chest, CT abdomen showing hepatosplenomegaly, negative ANA, normal C3 and C4 levels, negative urine Bence Jones protein, and normal serum hemoglobin electrophoresis.

TREATMENT AND PROCEEDINGS

She was started on intravenous dexamethasone 40 mg once daily for four days, with consultation with Hematologist.

After four days of dexamethasone, her hemoglobin improved to 5.9 g/dL. She was then transitioned to oral prednisolone at 1 mg/kg/day, supplemented with folic acid, and discharged. At her one-week follow-up, her hemoglobin had further improved to 7.4 g/dL, and her prednisolone dose was tapered with recommendations for continued follow-up.

CASE DISCUSSION

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is a condition where the immune system produces antibodies that attack and destroy red blood cells (RBCs), leading to hemolysis. AIHA is classified into warm AIHA and cold AIHA, based on the temperature at which antibodies react with RBCs. Warm AIHA involves autoantibodies (predominantly polyclonal IgG) that bind to RBCs at body temperatures of 37°C or higher, causing RBC destruction in the spleen and liver. This form of AIHA has an incidence of approximately 1–3 cases per 100,000 individuals per year and can occur at any age, though it is more common in adults.

Pathophysiologically, IgG autoantibodies bind to RBC antigens and Fc receptors on phagocytes, leading to increased extravascular hemolysis as macrophages in the spleen and liver phagocytose and destroy the RBCs. The condition is mostly idiopathic but can also be secondary to malignancies (e.g., lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia), autoimmune diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus), and certain drugs (e.g., rifampin, phenytoin, penicillins, α-methyldopa). Clinically, patients exhibit symptoms of anemia such as pallor, fatigue, and weakness, and mild splenomegaly, with a gradual onset of symptoms.

Diagnosis involves initial investigations including complete blood count (CBC), reticulocyte count, hemolysis workup (e.g., lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), haptoglobin, bilirubin levels), Direct Antiglobulin Test (DAT), and peripheral blood smear (PBS). A positive DAT for IgG ± C3d and the presence of spherocytes on PBS indicate warm AIHA. Additional tests may be necessary to rule out secondary causes.

Management of warm AIHA involves acute and long-term therapies. In cases of severe anemia (hemoglobin < 6–7 g/dL), hemodynamic and respiratory support are provided, and the blood bank is alerted for potential transfusion needs. Early treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids (e.g., methylprednisolone) is critical, and rescue therapy with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or plasma exchange may be considered. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis is necessary for patients with acute hemolysis, and type- specific uncrossmatched blood may be used if needed, in consultation with the blood bank. Long-term therapy aims to reduce autoantibody production, starting with high-dose glucocorticoids as the first-line treatment. Rituximab is used as a second-line treatment, and steroid-sparing immunosuppressants or splenectomy are considered for refractory cases. The overall goal of AIHA management is to control hemolysis and address underlying causes, with acute interventions focused on stabilizing the patient and long-term therapies aimed at preventing relapses.

REFERENCES

- https://www.thebloodproject.com/ autoimmune-hemolytic-anemia/

- Robbinsand Cotran- Pathophysiologic basis of disease

- Harrison’s Textbook of Internal Medicine – https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/ content.aspx?boo kId=3095§ionId=264134083

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ diagnosis-of-hemolytic-anemia-in-adults

- https://www.uptodate.com/ contents/warm-autoimmune-hemolytic-anemia-aiha-in-adults

Dr Vignesh A S

Dr Vignesh A S Dr Sivaram Kannan MD (General Medicine), FRCP

Dr Sivaram Kannan MD (General Medicine), FRCP Dr Arshad Raja M.B.B.S, M.D. (Transfusion Medicine),

Dr Arshad Raja M.B.B.S, M.D. (Transfusion Medicine),