Dr Sivasankar Jayakumar graduated in 1999, and has more than 15 years of work experience in the UK. He did his basic surgical training in Birmingham, UK and has completed Paediatric surgery fellowships at Great Ormond street hospital and Kings College London, UK. He was also a clinical teacher in surgery, at the University of Birmingham and is also accredited with a PG certificate in medical education. He is a keen academician and has more than 50 international presentations and publications.His interests include Paediatric Urology, Laparoscopy, Thoracoscopy, Endoscopic procedures, Neonatal surgery and Paediatric surgical oncology including vascular access.

He has completed MRCS from the Royal College of surgeons UK. He obtained European diplomat in Paediatric surgery and is a fellow of the European board of paediatric surgeons. He is also a member of the: Royal College of surgeons and physicians Glasgow, UK, British association of paediatric surgeons, UK, and Indian association of paediatric surgeons, Society of Paediatric Urologists, India.

Vesico-ureteric Reflux [VUR] in Children

Vesico-ureteric reflux [VUR] is abnormal reverse flow of urine from the bladder back to the kidneys. VUR is the most common urological problem associated with urinary tract infection (UTI) in children. Most of the VUR are congenital (Primary) however they can occur following conditions causing bladder outlet obstruction (Secondary).

- How common is VUR?

It is seen in almost one third of children presenting with urinary infection (UTI) symptoms and also in 1- 2% in the general population. In infants the incidence is much higher among boys while in older children the incidence is reported to be higher among girls.

- Why does VUR occur in some children?

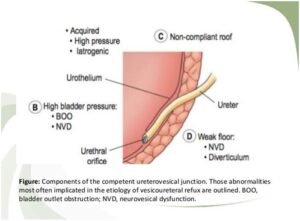

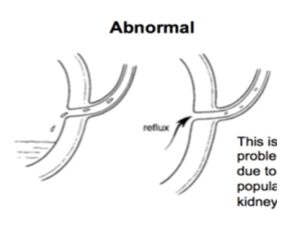

During voiding or micturition the urinary bladder contracts, while the bladder outlet is closed raising the pressure within the bladder. The oblique insertion of ureters into the urinary bladder creates a submucosal tunnel that closes with the raised bladder pressures during voiding and thereby prevents the urine flowing back into the ureters. This structural anatomy is altered in children with VUR and therefore urine refluxes into either one or both the ureters (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Illustration of the normal ureteric oblique insertion and the abnormal wide and straight ureteric insertion are seen

- What causes VUR?

It is still unclear what exactly causes VUR. The basis for VUR is thought to be genetic. 30-50% of first-degree relatives of VUR patients are diagnosed to have VUR. The risk is highest among the siblings of VUR patients diagnosed before 3 years of age. Studies from Dublin, Ireland where VUR has been studied in detail, recommend screening all siblings of patients with high grades (III to V) of VUR.

Most of the VUR are primary with a congenital pathology. However, VUR can be secondary due to raised or dysfunctional bladder pressures as seen in urological conditions like posterior urethral valves, bladder diverticulum, neuropathic bladder and voiding dysfunction syndromes. Ectopic ureters are usually associated with ureterocele and duplex system, which can also lead to significant VUR.

- What are the symptoms and signs of VUR?

VUR by itself does not produce any clinical signs and symptoms and therefore most children and infants with VUR are asymptomatic. However urine infections (UTI) occur commonly in VUR patients and may present with urinary symptoms such as painful voiding or burning sensation on voiding, blood stained urine, cloudy urine, frequent voiding, urgency to pass urine and dribbling urine. Patients can also have fever, vomiting and loin pain.

VUR should be suspected in all infants and younger children presenting with febrile urine infection (UTI) or recurrent urine infections.

- What tests are done for VUR?

The NICE guidelines from UK recommends that all children presenting with urine infection (UTI) under the age of 6 months should undergo an Ultrasound scan (USS) and micturating cysto-urethrogram (MCUG) and a DMSA scan.

Ultrasound scan (USS) is a valuable non-invasive test that can reveal dilatation of kidney and urine collecting system. Urinary bladder volumes before and after voiding can be calculated and these help in diagnosing bladder dysfunction, which could be the underlying cause for VUR. Impaired kidney growth and scarred kidneys can also be picked up on ultrasound scan (USS).

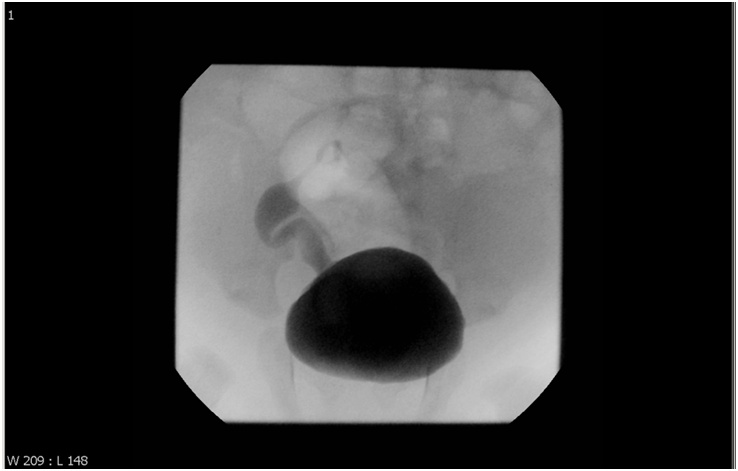

VUR is diagnosed on MCUG (Micturating cysto-urethrogram) scan and it is the gold standard diagnostic test [Figure 2]. Compliance is an issue in children; but infants tolerate the procedure well. MCUG not only diagnosis VUR but also grades the VUR and also provides valuable information on bladder neck and urethra, thus identifies any obstruction or secondary causes of VUR.

Figure 2: MCUG showing VUR on the right sided (Grade III)

Nuclear renal imaging involves injection of radio-isotope material and obtaining images at various intervals. DMSA scan (Figure 3)is most commonly done in these patients and this test provides information on the kidney function and shows kidney scarring. Timing of these scans is particularly important and should not be carried out within the first 3 months immediately after a urine infection (UTI). If done earlier results may be inaccurate.

Figure 3: DMSA scan of a patient, showing a reduced uptake in one of the kidney

- How is VUR Diagnosed?

The MCUG (micturatingcystourethrogram) scan is the standard diagnostic test for VUR worldwide. The scan involves putting a tube a catheter into the urethra (urine pipe) and injecting dye (contrast) to fill the urinary bladder and taking x-ray images whilst the patient voids. As per the MCUG scan VUR is graded into 5 grades (Figure: 2).

- Grading or Severity of VUR

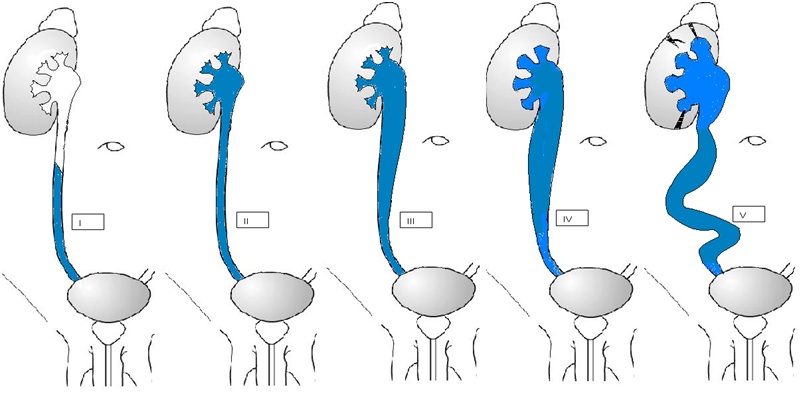

The international reflux grading system classifies VUR into 5 grades – I to V. The classification is based on the x-ray (radiological) findings on MCUG scan (Figure 4). In Grades 1 and 2 VUR, the reflux of urine is limited to lower ureter. These VUR are described as mild VUR and can be managed with oral antibiotics and conservative measures. However, if urine refluxes back into the kidney the grade of VUR is considered 3 and above. Higher grades (3 to 5) of VUR are considered significant and surgical interventions are usually necessary.

Figure 4: Classification of grades of vesicoureteral reflux by International Reflux Study Committee

Grade I: reflux into ureter only. Renal function is affected.

Grade II: reflux into ureter, pelvis, and calyces. There is no dilation, and calyceal fornices are normal. Renal function is usually not affected.

Grade III: mild or moderate dilation, and/or tortuosity of the ureter and moderate dilation of the renal pelvis but little or no blunting of the fornices. Renal function may be affected.

Grade IV: moderate dilation and/or tortuosity of the ureter and moderate dilation of the renal pelvis and calyces. Renal function is affected.

Grade V: gross dilation and tortuosity of the ureter and gross dilation of the renal pelvis and calyces. There is complete obliteration of the sharp angle of the fornices. Renal function is affected.

- Management of VUR

Preservation of kidney function and bladder function forms the mainstay of management in children with VUR. The damage from VUR alone is far less and preventing urine infections (UTI) is the key to preserve existing renal function. Almost in a third of the children diagnosed with VUR, the reflux resolves spontaneously but in a third it remains static and in the remaining it progresses to cause severe renal damage.

- What are the Complications of VUR?

The most worrying outcome of VUR is reflux nephropathy [RN]. Patients with VUR may develop scarred kidneys and impaired growth of kidneys, which collectively is called as reflux nephropathy [RN]. Reflux nephropathy leads to loss of kidney function and high blood pressure (hypertension). A combination of urine infection (UTI) with high grade VUR is known to cause RN.

- Do all patients with VUR need treatment?

In infants and younger children the submucosal tunnel of ureter is short and more straight, but as the children grow the length of the tunnel increases and so the bladder pressures. This change possibly explains the spontaneous resolution of VUR in some children. Low grades of VUR (grade 1 and 2) are most likely to resolve and will only need observation. The grade of reflux is the strongest predictor of VUR resolution, with high-grade VUR being much less likely to resolve on its own.

- Role of antibiotics and medical management

Traditionally continuous use of prophylactic antibiotics like Trimethoprim, Cephalexin and Nitrofurantoin has been used to try to reduce the incidence of urine infections (UTI) in VUR and thereby preventing subsequent renal damage. However the use of prophylactic antibiotics has been recently questioned and it’s debatable if it will benefit the children with VUR. Literature review reveals conflicting results. Currently, it is an acceptable practice to recommend prophylactic antibiotics in children with high grade VUR (III – V).

- Role of surgery

Indications for surgical intervention include high grade VUR with a drop in kidney function, failed conservative management, recurrent breakthrough urine infections (UTI) and persistent reflux after the age of 5 years. Options for surgical interventions are open surgery (Ureteric Reimplantation) for correction of VUR and Endoscopic correction (STING / HIT procedure) of VUR. The main principles behind surgery are to increase the submucosal l tunnel and thereby preventing reflux of urine. Various open surgical techniques for correcting VUR are described but Cohen and Lich – Gregoire remain popular. Circumcision is also offered in boys, to reduce the risk of future urine infections. It is beneficial in particular to high grade VUR patients and has shown to reduce the risk by at least 30%.

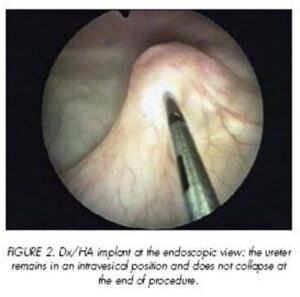

Endoscopic correction of VUR (STING / HIT procedure) is a relatively new surgical approach where an inert material is injected submucosally below the ureteric office opening in the bladder (Figure 6). The first data on Endoscopic Subureteric Teflon injection (STING) in piglets was published in 1984. Since then this technique has popularised and widely being used for correction of VUR. In the subsequent years TEFLON injection has been replaced by DEFLUX, which was first introduced in 1998.

Figure 6: Photograph taken whilst a STING procedure where DEFLUX injection has been injected and a mound created at the ureteric orifice opening

The reported success rates of endoscopic DEFLUX correction of VUR vary significantly from 60 – 85% with one injection but improves up to 93% with second DEFLUX injections. Although the endoscopic correction is a simple, a less invasive technique, the recurrence rate of reflux is slightly higher than open surgical techniques which have a success rate of 95%.

Dr. Sivasankar Jayakumar

Dr. Sivasankar Jayakumar

MBBS, MRCS, PGCME, FEBPS (UK)

Consultant Paediatric surgeon and Paediatric Urologist

Kauvery Hospital Chennai

![Vesico-ureteric Reflux [VUR] in Children](https://www.kauveryhospital.com/ima-journal/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/bg-ima-july-23-1200x545_c.jpg)