Vascular access is required to assist in the management of patients requiring frequent venous or arterial cannulation. Its principal role is to provide circulatory access for haemodialysis, although such techniques are also used to provide chemotherapy, intravenous nutrition, and access for plasma exchange.

There are mainly two techniques used which are either implantable synthetic lines, which may have one or more lumen which may be temporary or tunnelled, or a surgically created fistula between the arterial and venous circulation. This latter approach may involve joining artery and vein together, the so-called autogenous arteriovenous fistula (AVF), or the insertion of a synthetic graft between artery and vein (Non-autogenous AV access).

Principles of Vascular Access

The main principles of access surgery is to use AVF in preference to synthetic grafts and these in turn are preferred to in-dwelling central venous catheters. Access should be placed as far distally in the chosen limb as possible. This helps conserve veins to permit proximal revision if the initial procedure fails. An exception is very old patients, who often have poor distal vessels. The non-dominant limb should be used wherever possible. In patients who may require vascular access, venepuncture, phlebotomy or the insertion of intravenous cannula in the main named veins of the upper limb, should be avoided. If central venous catheters are required, they should be sited in the jugular and not the subclavian veins since subclavian vein is more prone for thrombosis.

In India, unfortunately most patients still are started on dialysis with a temporary catheter before being referred to a vascular surgeon for AV access. Temporary and implanted access lines cannot be used for long and have many complications of their own the most common being infection and thrombosis leading to central vein stenosis.

International guidelines recommend that the majority of patients starting dialysis should do so using a native vessel AVF at the wrist. Grafts require six times as many interventions as AVF to achieve the same patency, and their use is discouraged. Central catheters have inferior patency and are discouraged for “permanent” access. Their principal role should be for emergency or temporary access.

Types of Access

The principal modes of vascular access are autogenous AVF, synthetic AV bridge grafts (Non-autogenous AV access), and in-dwelling synthetic central venous catheters. Consideration of patient demographics, anatomical suitability, and other factors are important in the preoperative planning for access. Previous access attempts/subclavian vein cannulations and possibility of central venous pathologies must be ruled out.

The patient should be optimized for operation (e.g., address cardiac, metabolic, volume status, nutritional, infectious issues) and should not be in fluid overload, pulmonary edema or coagulopathy.

Arteriovenous Fistula

This is the most durable form of vascular access. The preferential site is between the cephalic vein and the radial artery at the anatomical snuffbox, or the wrist, in the nondominant upper limb called the Brescia-Cimino fistula (Brescia et al., 1966). The end of the vein is joined to the side of the radial artery, usually under local anaesthesia. The success of this procedure is dependent on the quality of the vein and artery and the technical skill of the surgeon. Where good vessels are not clinically evident, duplex ultrasonography may help to identify the best sites for access formation. Widely varying success rates are quoted, but about 60% of wrist AVFs mature and become useful for dialysis in 6-8 weeks. Many factors may affect maturation, such as the size of artery and vein, change in flow, and the presence or absence of arterial disease (e.g., diabetes). For this reason, in those in whom the need for access can be anticipated, every effort should be made to avoid needling the cephalic vein, the antecubital veins, or the subclavian vein. The radial artery at the wrist is often insufficient in the elderly and particularly those with diabetes due to arteriosclerosis with calcification. Native AV fistula can also be created at elbow between brachial artery and cephalic vein.

The basilic vein is another option. The depth of the basilic vein within the arm complicates its use as a direct fistula. This vein, however, may be easily mobilized through a longitudinal incision in the medial arm. The basilic vein is then divided distally, tunnelled subcutaneously, and anastomosed to the brachial artery in the distal arm. Such transposed fistulas may give good service over many years.

Synthetic Access Grafts (Non-autogenous Arteriovenous Access)

Where veins are inadequate, AVF may be inappropriate. In such circumstances, access can be established using synthetic bridge grafts between suitable arteries and veins. Grafts tend to be placed more proximally in the limb than AVFs. They may be placed in either straight or curved/looped configurations in the forearm or upper arm depending on the availability of a good vein. Although easier to establish, PTFE grafts are known to have higher thrombotic and septic complication rates, and to need more frequent revision than native AVFs. For this reason, it is advised that AVFs are preferred.

Central Venous Catheters

Many patients may present with acute or acute on chronic renal failure. Those requiring emergency access (e.g., immediate need for dialysis) need the insertion of a dual-lumen central venous catheter. These should be left in place for as short a time as possible. Definitive access surgery should follow as a matter of urgency. Central catheters become infected easily, and often have to be removed or re-sited. In addition, they stimulate fibrosis in the veins and can cause stenosis. For this reason, subclavian lines are to be avoided, as the loss of the subclavian vein prejudices further access in the ipsilateral upper limb. Lines should be placed via the jugular route if at all possible. If access is needed only for a few days, then in the absence of suitable jugular veins the femoral veins may be used. Patients needing more permanent catheters (longer than 3 weeks) should have tunnelled catheters inserted. Placement considerations are the same as for temporary lines. Tunnelled catheters should be cuffed, as the cuffs reduce the risk of infection from the site of skin entry.

Complications of Vascular Access

Few important complications of various access options include:

Technical Failure- The most immediate complication of AV access is that the fistula occludes shortly after formation. This may be due to obvious problems such as inadequate vessels or to technical imperfections in the procedure

Failure to Mature -Failure to mature is the most common problem seen in AVFs. Fistulas demonstrate significant increase in flow within 48 hours and enlarge thereafter. Ideally, AVFs should be placed well in advance of the time that they are likely to be required Flow rates greater than 500 mL/min signify that the fistula is likely to develop successfully. Scanning can also be used for the early detection of technical deficiencies, stenoses, and other problems

Vascular Stenosis – Vein stenosis and aneurysmal dilatation are both seen following development of AVFs. The former may compromise both the quality of dialysis and the longevity of the fistula. Stenoses within 1 to 2 cm of the anastomosis are most easily dealt with by balloon angioplasty. This can be undertaken under local anaesthesia. Stenosis can also develop at the puncture site

Vascular Steal and High-Output Cardiac Failure- Proximal fistulas tend to have higher flow rates and may divert blood from the hand. Temporary finger occlusion of the AVF can assist in determining whether there is an inflow problem, or whether the arterial flow distal to the arterial anastomosis has been interrupted. High fistula flows can also cause high-output cardiac failure, which is seen more commonly in proximal AVFs. In these cases, fistula revision to reduce flows is required.

Infection- Infection is rare, but if associated with bacteraemia, abscess, or aneurysm formation, revision is usually required. The clinical features are of an area of inflammation in relation to the fistula, sometimes with rapid enlargement. Fever and rigors, particularly on dialysis, may be seen, but are not a universal feature. Sudden rapid bleeding can occur at infected needling sites. Immediate pressure and placement of a skin suture will achieve acute control, but should be followed by a definitive revision in most cases.

Thrombosis -Thrombosis is uncommon, but when it occurs it can often be retrieved by acute intervention, with salvage of the fistula and avoidance of temporary central lines. Dilatation of fistula or central vein stenosis may be required to restore normal function. The complications associated with transposed fistulas are the same as those seen with other native AVFs. They tend to have high flows, so cardiac failure and steal are more common in these fistulas.

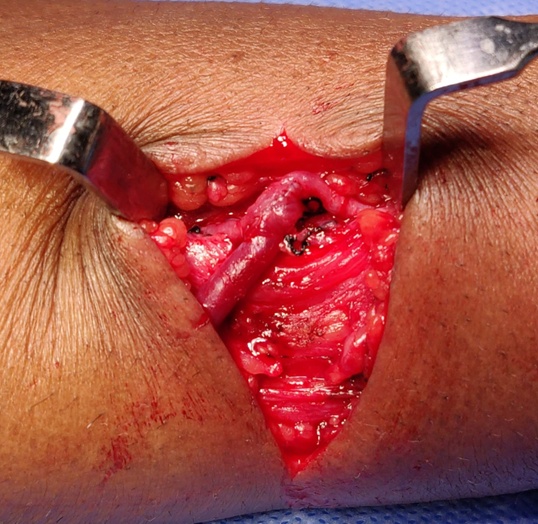

Fig 1: Intra-op picture showing Arterio-venous anastomosis and fistula creation

Fig 2: Ulnar-basilic AV Fistula

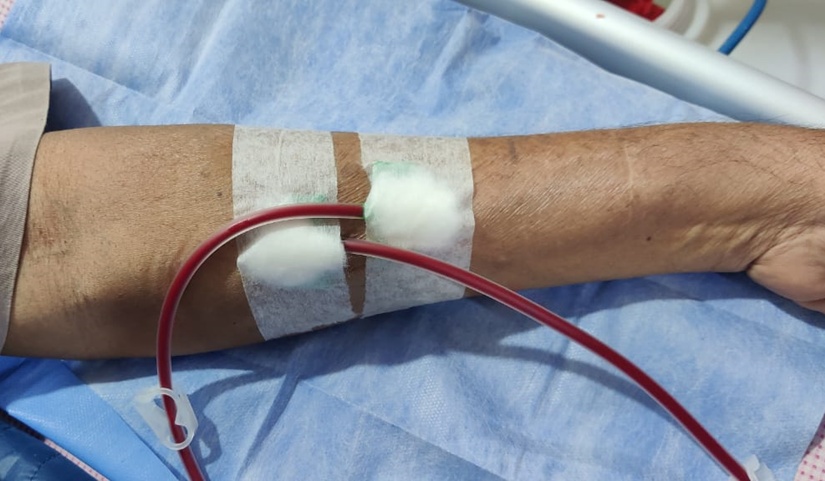

Fig 3. Showing cannulated AV Fistula for haemodialysis

Dr. Dhilipan Pradap R

Dr. Dhilipan Pradap R