Case description:

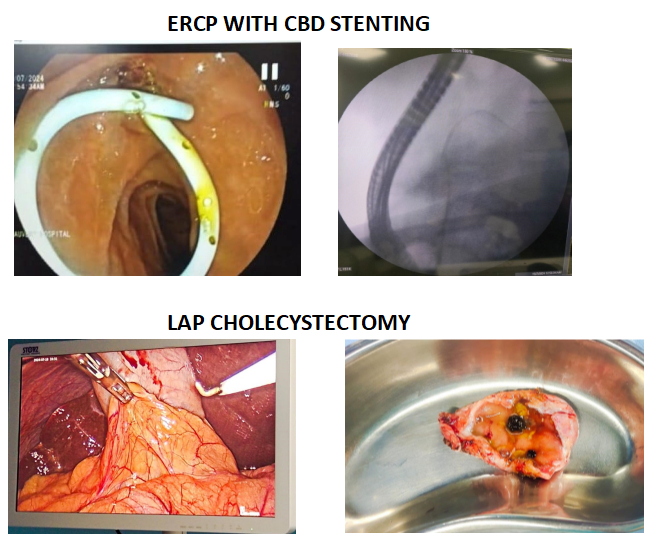

Mr D, a 55-year-old male, was admitted to our hospital with complaints of sudden onset upper abdominal pain. The patient had a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, CAD (S/P PTCA), and hypothyroidism. He also had chronic kidney disease, and was on haemodialysis. He was recently managed for Gallstone pancreatitis, for which ERCP with plastic stenting of the bile duct and laparoscopic cholecystectomy were performed 8 days prior to current admission.

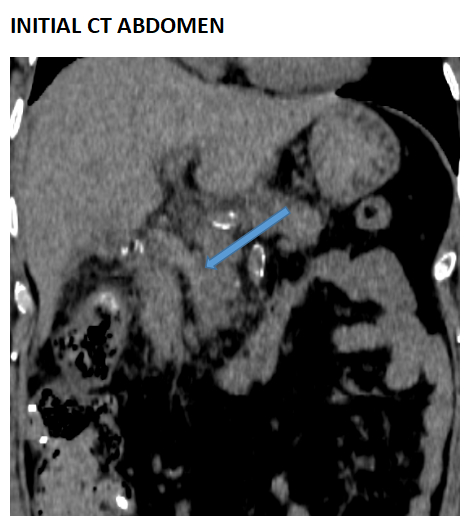

A systemic examination performed upon admission showed a soft abdomen with epigastric tenderness. He was advised abdominal CT scan and liver function test. His vitals were stable at admission.

The abdominal CT showed hyperdense material in the common bile duct? sludge and The stent previously placed in the common bile duct had been displaced out into GI Lumen. The patient’s hemoglobin showed a mild drop, indicating possible bleed. However there was no clinically appreciable bleeding from anysite. The LFT revealed mild transaminitis.

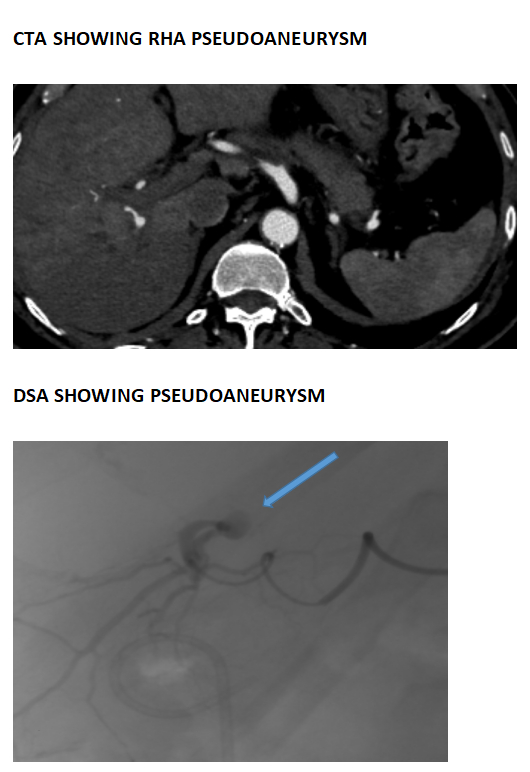

The following day there was one episode of fresh bleeding per rectum followed by two episodes of melena. CT Abdominal Angiogram was recommended with suspicion of hemobilia. It showed a pseudoaneurysm formed in the segment 6 artery, which – branches off the right hepatic artery.

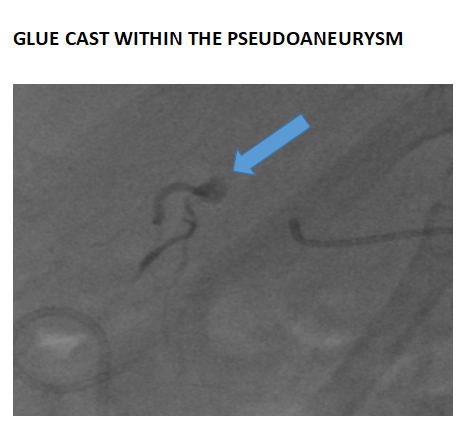

Promptly, a glue embolization was done to block the artery.

A CT abdomen was performed as a follow up to the previous day’s embolization procedure. The CT showed fluid collection in the gall bladder fossa, and an enlarged pancreas with surrounding inflammatory changes, indicating resolving mild pancreatitis. The displaced common bile duct stent was found in the distal ileum/caecum region.

Our patient would remain in the ward for few days before being discharged in stable condition with no recurrence of GI Bleed.

DISCUSSION:

Historical perspective of Hemobilia

Hemobilia was first recorded in 1654 by British physician Francis Glisson. He described the clinical presentation of a nobleman who suffered a fatal blow from a sword to the right upper quadrant, leading to upper GI bleeding and death. Post-mortem, the source of bleeding was found to be a liver laceration, which in turn led to the landmark description of hemobilia. The first case of hemobilia identified pre-mortem was in 1777, by Antonie Portal. A century later, Quincke identified the three classical symptoms of haemobilia Quincke’s triad.

The term ‘hemobilia’ itself was coined only in 1948.

Clinical Presentation:

The classical presentation of hemobilia is Quincke’s triad– jaundice, epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, and upper GI bleeding. However, all three occur together only in 22-35% of cases- in the aforementioned case jaundice was not observed, but LFT derangement was present.

Causes:

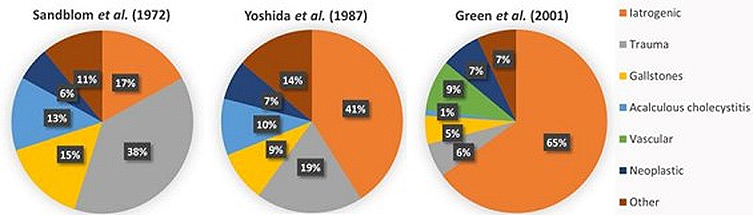

Hemobilia can have iatrogenic, trauma ,neoplastic, , infectious and vascular etiologies. Though trauma has been the main cause

historically, iatrogenic causes have superseded others in recent years due to an increased number of complex procedures being done in the liver, pancreas and biliary tree.

- Iatrogenic causes:

- Percutaneous interventions

- Endoscopic interventions

- Surgical interventions

- Malignancy

- Portal biliopathy

- Tropical haemobilia (Biliary worm infestation)

HEMOBILIA -CAUSES OVER THE YEARS

Diagnosis:

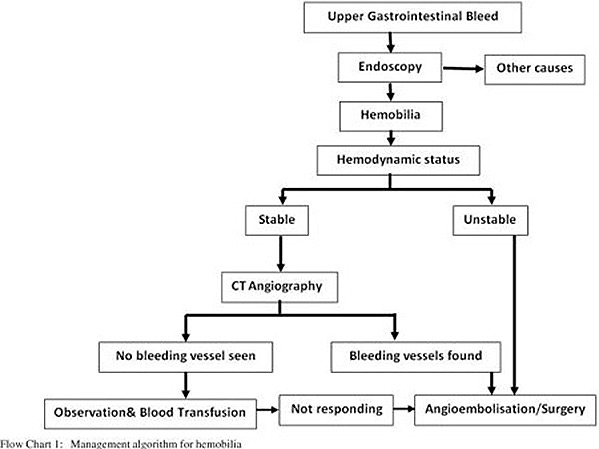

Hemobilia should be suspected in any patient with an unclear source of GI bleed, recent trauma to the upper abdomen or any biliary instrumentation or manipulation. The following imaging techniques are helpful in making a diagnosis of hemobilia:

- CT abdomen/MRCP

- Upper GI endoscopy

- Angiography

Management:

Minor hemobilia can be treated conservatively, with little more than IV fluids and correction of coagulopathy being required. Major hemobilia, involving significant decrease in haemoglobin and/or persistent upper GI bleeding, requires endoscopic, radiologic (embolization), or (rarely) surgical intervention. Patients with haemodynamic instability should immediately be considered for angiography and embolization which has a 90% success rate in management. If signs of infection are detected, they must be promptly administered broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics.

Conclusion:

Hemobilia is a rare but important cause of upper GI bleeding. Iatrogenic causes are the main causes of hemobilia. It classically manifests as Quincke’s triad. Prompt recognition decides good

outcomes. Treatment is mainly by angioembolization of involved vessel if bleed is significant, and with backup interventional endoscopic or surgical options.

Bibliography:

- Berry, R., Han, J., Kardashian, A.A., LaRusso, N.F. and Tabibian, J.H. (2018). Hemobilia: Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Liver Research, [online] 2(4), pp.200–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livres.2018.09.007.

- Green M, Duell R, Johnson C, Jamieson N (2001). “Haemobilia”. The British Journal of Surgery. 88 (6): 773–86. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01756.x. PMID 11412246. S2CID 221527400.

- John Hopkins Medicine (2019). Endovascular Coiling. [online] John Hopkins Medicine. Available at: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/endovascular-coiling.

- Prasad, T. (2015). Minimally invasive image-guided interventional management of Haemobilia. Tropical Gastroenterology, [online] 36(3), pp.179–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.7869/tg.280.

- Quincke H (1871), Ein fall von aneurysma der leberarterie. Berl Klin Wochenschr; 30: 349–352.

Authors

Dr. M. A. Arvind

Dr. M. A. Arvind

Senior Consultant Medical Gastroenterologist

Kauvery Hospital, Chennai

Dr. Sathya Narayanan R

Dr. Sathya Narayanan R

Consultant Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology

Kauvery Hospital, Chennai

Dr. Muralidharan Parthasarathy

Dr. Muralidharan Parthasarathy

Consultant – General, GI, Laparoscopic & Bariatric Surgeon

Kauvery Hospital, Chennai

Ms. Nishithaa V

Ms. Nishithaa V 2nd Year Medical Student

2nd Year Medical Student