Journal scan: A review of 10 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

From the desk of the Editor-in-chief

Chilblain Lupus Erythematosus

(1). Wei-Yao Wang etal,.Published July 24, 2024,N Engl J Med 2024;391 : e6, DOI: 10.1056/NEJicm2400724,VOL. 391 NO. 4

A 29-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus presented to the dermatology clinic with a 2-week history of an itchy, painful rash on her nose and hands. The rash had first appeared 1 day after the weather had turned cold. The patient reported no sun exposure. The physical examination was notable for erythematous macules and papules with punched-out ulcers on the nose (Panel A). Scattered papules were seen on the palms, and edematous erythrocyanosis of the fingertips (Panel B) with ulcerations on the lateral aspects (Panel C) was noted. Blood tests were positive for antinuclear antibodies, anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies, rheumatoid factor, anti-Ro antibodies, and antiphospholipid antibodies, and hypergammaglobulinemia was present. Cryoglobulin and cold agglutinin testing was negative. Histopathological examination of a biopsy specimen of the right nasal sidewall revealed vacuolar interface dermatitis and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. A diagnosis of chilblain lupus erythematosus was made. Chilblain lupus erythematosus is an uncommon form of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The inflammatory skin lesions are precipitated by exposure to cold and typically occur on the hands and feet; involvement of the nose is uncommon. Treatment with glucocorticoids, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, and nifedipine was initiated. Counseling regarding cold avoidance was also provided. At a 2-week follow-up visit, the skin lesions had abated.

Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis

(2). Atif S. Siddiqu I et al, Published July 27, 2024, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMicm2402620

A 60-year-old man with hypertension presented to the emergency department with a 4-month history of hemoptysis and painful lumps on his neck. On physical examination, palpable masses were noted on both sides of the lower neck with purulent drainage from the left side. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus was negative. The glycated hemoglobin level was 5.0%. Computed tomography (CT) of the neck showed enhancing fluid collections in the supraclavicular region on both sides (Panel A, arrows). CT of the chest showed a cavitary lesion in the left upper lobe and tree-in-bud opacities in both lungs (Panel B). The supraclavicular fluid collection on the right side was incised and drained. The results of a histopathological analysis of a tissue sample were consistent with an abscess. Scattered fungal spherules (Panel C, Grocott’s methenamine silver staining) containing endospores (Panel D, hematoxylin and eosin staining) were seen, a finding consistent with coccidioides infection.

Serum coccidioides immunodiffusion and complement-fixation antibody assays were positive. A polymerase-chain-reaction assay of a surgical tissue sample showed Coccidioidomycosis immitis. A diagnosis of disseminated coccidioidomycosis was made. How the patient had acquired the infection was unknown, since he had not left Houston, Texas, in 15 years. Treatment with a prolonged course of oral fluconazole was initiated. At a 2-month follow-up, his symptoms had abated.

Management of Patients with Chronic Coronary Disease

(3). German CA, Davis AM, Polonsky TS. Management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease. JAMA. 2024;332(7):585-586. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.9813

Guideline title 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients with Chronic Coronary DiseasDeveloper and Funder American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC). Release date August 2023

Target population Patients with chronic coronary disease (CCD)

Selected recommendations

- Physical activity and a diet of fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, whole grains, and lean protein are recommended for all patients with CCD to reduce risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events (class of recommendation [COR]: 1; moderate level of evidence [LOE]).

- High-intensity statins should be used for lipid lowering in patients with CCD (COR: 1; high LOE). Ezetimibe (COR: 2a; moderate LOE), proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors (COR: 2a; high LOE), bempedoic acid (COR: 2b; moderate LOE), or inclisiran (COR: 2b; moderate LOE) may be added for selected patients.

- Patients with CCD should participate in cardiac rehabilitation (COR: 1; high LOE for recent myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass graft surgery; moderate LOE for stable angina or after heart transplant).

- In patients with CCD and limiting angina despite guideline-directed management, coronary revascularization is recommended to reduce symptoms (COR: 1; high LOE).

- A sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor or a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP1-RA) is recommended for patients with CCD and diabetes to reduce risk of major adverse CVD events (MACE) (COR: 1; high LOE).

- β-Blocker therapy is not recommended in patients with CCD unless they have had a myocardial infarction in the past year, left ventricular ejection fraction of 50% or lower, or another primary indication for β-blocker therapy (COR: 3; moderate LOE).

(4). Nathaniel Klair et al,. Leukaemia presenting as spontaneous bilateral perinephric haematomas: a case of Wunderlich syndrome. The Lancet VOLUME 403, ISSUE 10428, P766-767, Feb 24, 2024. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00089-8

A 62-year-old woman presented to our hospital with a 2-h history of abrupt-onset of right flank pain and vomiting.

The patient had a history of vertigo and recent unintentional weight loss with migrating lymphadenopathy. She was prescribed meclizine and loratadine. She reported no history of trauma.

View related content for this article

On examination the patient was distressed and pale; pulse was 75 beats per min, blood pressure 96/53 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation was 95%; her temperature was 36·6oC. She had tenderness in the right periumbilical region of her abdomen, with no rebound or guarding. Urine analysis showed 1+ protein, positive leukocyte esterase; microscopic examination showed 12 white blood cells, and 8 red blood cells.

Laboratory investigations found the patient to be anaemic with a haemoglobin concentration of 6·8 g/dL (reference range 11·7–15·7); she was given an emergency transfusion of packed red blood cells. Further tests showed a white blood cell count of 49 × 103 per μL (reference range 4·0–11·0), platelets 380 × 103 per μL (reference range 150–450), and serum creatinine concentration of 0·9 mg/dL (reference range 0·51–0·95).

A CT scan of the patient’s abdomen showed a large right perinephric haematoma. A renal angiogram showed no signs of active bleeding.

The patient was stabilised with further medical management involving intravenous crystalloid fluid and an additional transfusion of packed red blood cells. Given the profound leukocytosis and absence of signs of infection, oncology colleagues were consulted, and an outpatient bone marrow biopsy was planned.

However, 2 days later, the patient presented to our hospital again with acute onset pain in the flank, but this time on the left side; her haemoglobin concentration was 6·0 g/dL and she was thrombocytopenic—nadir of the platelet count was 7 × 103 per μL. She received a transfusion of platelets and further packed red blood cells.

An abdominal CT scan showed a new left perinephric haematoma; the right sided haematoma appeared stable (figure 1). A renal angiogram showed active bleeding from a left upper pole segmental arterial branch and a right upper pole peripheral arterial branch; these were then both successfully embolised. The patient then became oliguric and showed signs of acute kidney injury—peak serum creatinine concentration was 3·6 mg/dL.

Figure thumbnail gr1

Figure 1Leukaemia presenting as spontaneous bilateral perinephric hematomas: CT images in a case of Wunderlich syndrome

An MRI showed splenomegaly with numerous T2 hyperintense, hypo-enhancing lesions—indicating possible leukaemic infiltrates—as well as the perinephric haematoma (figure 2).

The patient required intermittent haemodialysis while her renal function recovered over the next 2 weeks. During this time, analysis of a sample obtained by bone marrow biopsy (figure 3) showed monocytosis—including atypical monocytes and slight dysgranulopoiesis—indicative of chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CMML); G-banded chromosomal analysis showed a 46, XX karyotype and genetic sequencing for common myeloid neoplasm-associated gene mutations showed CBL R420*, CBL C382S, IDH2 R140Q, and SRSF2 P95R mutations. Treatment with hydroxyurea was initiated and the patient was allowed home with oncology follow-up.

Over the next few weeks, the leukocytosis, anaemia, and thrombocytopenia essentially resolved; treatment with hydroxyurea continued and correlated with improvement in her energy and strength. Repeat renal imaging—both ultrasound and MRI—showed resolution of both perinephric haematomas and no obvious underlying renal masses. Renal function subsequently improved and creatinine returned to typical range.

The patient stayed on 500 mg of hydroxyurea daily for 10 months after her initial hospitalisation with no major complications from the CMML. She had a mild anaemia, a normal creatinine, and returned to her previous functional status—including returning to work.

Spontaneous renal or perinephric haemorrhage—known as Wunderlich syndrome—without any trauma—is rare. Causes include renal neoplasm, vascular disease, coagulation abnormalities, and infections. While CMML can result in acute kidney injury through a variety of mechanisms—including tumour lysis syndrome, renal thrombosis, extramedullary haematopoiesis, lysozyme induced nephropathy, and rarely renal infiltration—to our knowledge, no cases have been reported of an association with Wunderlich syndrome. Notably, in this case, contrast nephropathy, ischaemia following the embolisation and acute blood loss, compression of the kidneys, and possibly leukaemic infiltration, may have contributed to the patient’s acute kidney injury. Finally, we suspect leukaemic infiltration of both kidneys predisposed to the development of the spontaneous bilateral perinephric haematomas

Lemierre’s Syndrome Complicated by Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis

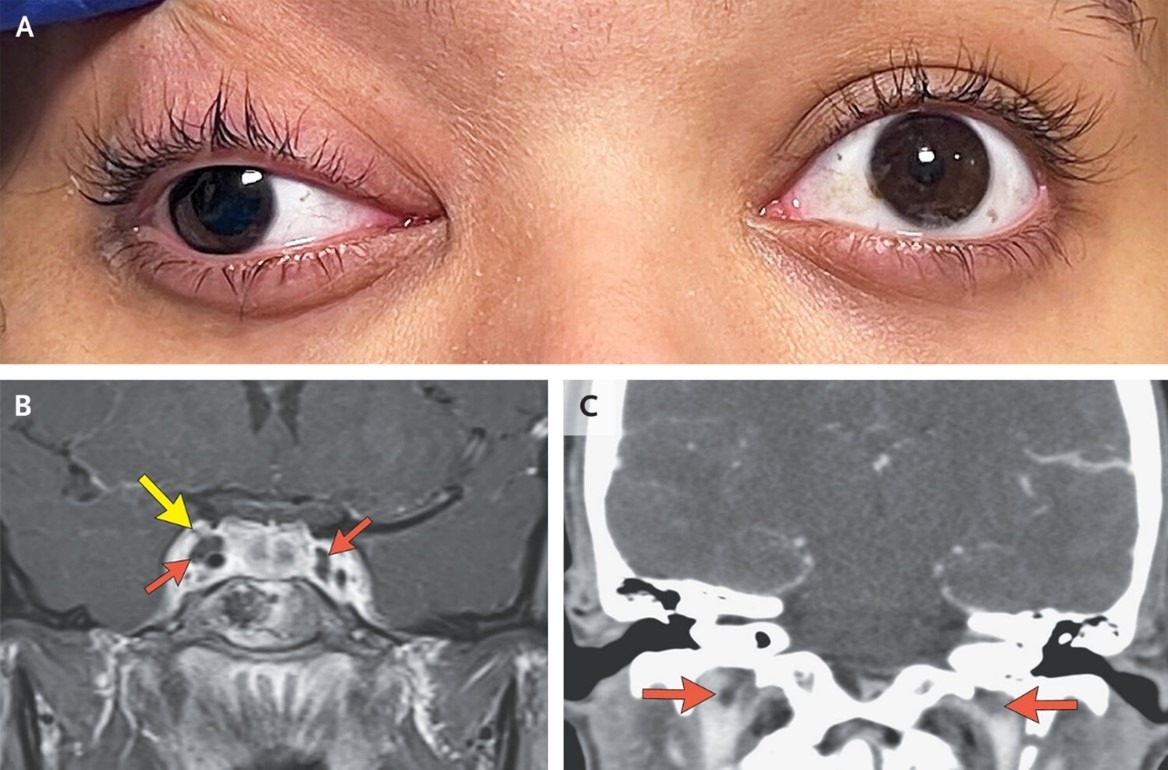

(5). Matthew J. Heron etal, Published August 3, 2024,DOI: 10.1056/NEJMicm2401083

Abstract

A 20-year-old woman presented with headache, double vision, and drooping of the right eyelid. Workup was notable for oculomotor nerve palsy and thromboses of the cavernous sinuses and internal jugular veins.

AL Amyloidosis

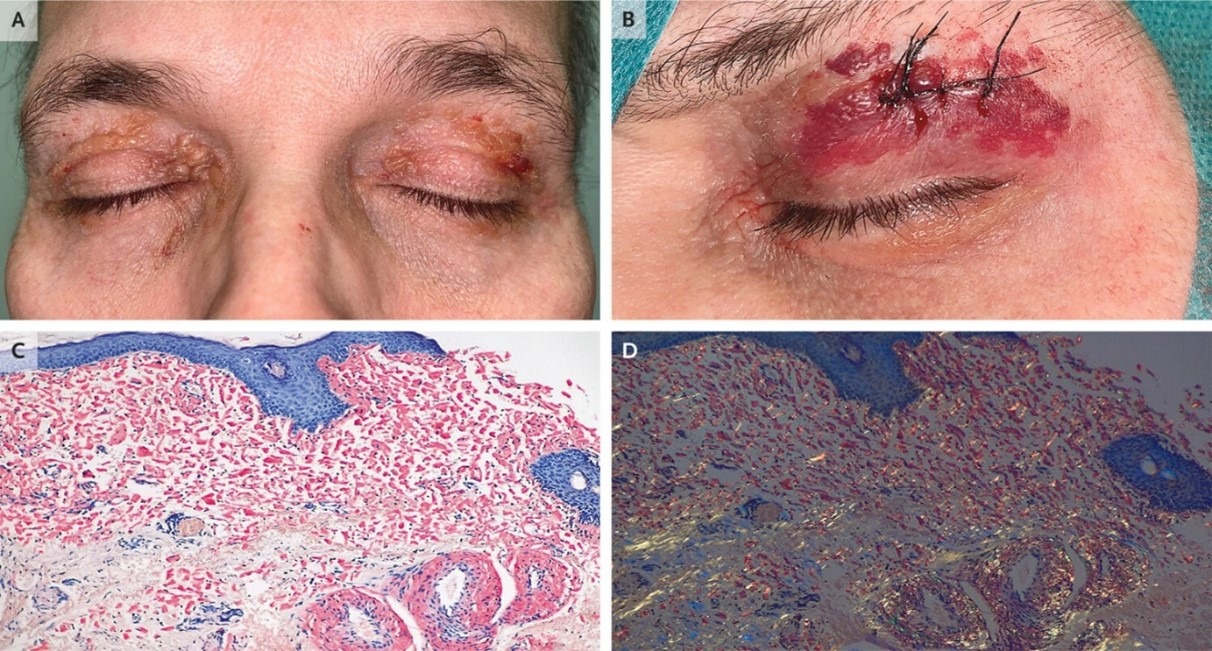

(7). Miguel Mansilla Polo et al, Published August 14, 2024,N Engl J Med 2024;391:640, DOI: 10.1056/NEJMicm2403455, VOL. 391 NO. 7

A 58-year-old man presented with a 2-year history of eyelid lesions and several months of weight loss and fatigue. Scattered periorbital petechiae and purpura were noted, as well as coalescing, waxy papules on the eyelids.

A 45-Year-Old With Multiple Skin Lesions on Sun-Protected Areas of the Body

(7). Sheng-Wen Liu, et al, JAMA. Published online August 22, 2024. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.15175

A45-year-old man without significant medical history was evaluated for multiple asymptomatic skin lesions on non–sun-exposed areas of the body, which first appeared in the bilateral axillae 8 years prior to presentation.

On physical examination, he had multiple erythematous macules and patches on the trunk; hyperpigmented patches on the intergluteal cleft and subgluteal fold; and atrophic, mottled, hypopigmented and hyperpigmented skin with telangiectasias (poikiloderma) in the axillae (Figure). There were no palpable lymph nodes.

Laboratory analysis revealed a normal complete blood cell count, normal liver function test results, and normal levels of lactate dehydrogenase, creatinine, and fasting plasma glucose. Results of antinuclear antibody testing were negative.

Physical findings at patient presentation. Left, Erythematous macules and patches on the trunk. Top right, Poikiloderma in the axillae. Bottom right, Hyperpigmented patches on the intergluteal cleft and subgluteal fold.

Diagnosis

Mycosis fungoides

What Would You Do Next?

- Arrange for T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangement testing

- Check for anti-Scl-70 and anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies

- Measure glycated hemoglobin level

- Perform a skin biopsy with immunophenotyping of lymphocyte markers

The key to the correct diagnosis is recognizing that persistent hyperpigmented patches and poikiloderma located on non–sun-exposed body areas are characteristic of mycosis fungoides, which is diagnosed with a skin biopsy. TCR gene rearrangement testing (choice A) is performed only when mycosis fungoides is suspected and initial skin biopsy is inconclusive. Checking for anti-Scl-70 and anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies (choice B) is not recommended because the patient’s skin findings are not characteristic of systemic sclerosis. Screening for diabetes (choice C) is not indicated because the lesions are not consistent with acanthosis nigricans.

Discussion

Mycosis fungoides is the most common primary cutaneous lymphoma, constituting nearly 50% of all cases.1 The incidence in Europe and the US is estimated at 5.42 per million per year, and the incidence has increased annually by 1.34% over the past 2 decades.2 The median age of diagnosis is 55 to 60 years, with a male to female ratio of 2:1.3

The World Health Organization and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classify mycosis fungoides into classic mycosis fungoides (88.6% of cases) and 3 variants.4 Classic mycosis fungoides is a slowly progressive disease that occurs primarily on non–sun-exposed areas of skin and appears first as cutaneous patches, then cutaneous plaques, and later as exophytic or ulcerated tumors.3,4 Findings of poikiloderma are suggestive of early mycosis fungoides, and pruritus is present in 80% of patients with mycosis fungoides.4 Extracutaneous mycosis fungoides may occur rarely and can involve the lymph nodes, spleen, liver, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract.

The pathogenesis of mycosis fungoides is not fully understood but involves clonal proliferation and malignant transformation of skin-homing CD4+ memory T cells. No clear evidence supports any infectious, pharmacological, environmental, or occupational exposures as risk factors or causes of mycosis fungoides.3

The differential diagnosis of mycosis fungoides includes eczema, psoriasis, drug reactions, contact dermatitis, and other cutaneous B-cell and T-cell lymphomas.

Diagnosis of mycosis fungoides is made with skin biopsy of patches or plaques, which typically reveals a bandlike lymphoid infiltrate in the superficial dermis, with atypical lymphocytes extending into the epidermis (epidermotropism). In tumor lesions, the neoplastic lymphoid infiltrate extends into the dermis. In 80% of cases, a CD4+/CD8– immunophenotype predominates in the lymphoid infiltrate.5 The diagnosis is further supported by absence of antigens characteristic of normal T cells such as CD2, CD3, CD5, and CD7.

Staging of mycosis fungoides is based on evaluation of the skin (T), lymph nodes (N), metastases (M), and blood (B) and requires estimation of skin involvement; evaluation of lymph nodes (with biopsy of lymph nodes that are larger than 1.5 cm, firm, or fixed); assessment for other organ involvement with physical examination and basic laboratory assessment; and testing peripheral blood for atypical lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei (Sézary cells).4,6 Individuals with extensive cutaneous mycosis fungoides findings or possible extracutaneous involvement should undergo computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis or a positron emission tomography (PET)–CT scan to accurately stage mycosis fungoides.

First-line therapy for early-stage mycosis fungoides, defined as stages IA to IIA, includes topical steroids and phototherapy, administered either as narrowband UV-B or psoralen plus UV-A (PUVA), which penetrates deeper into the dermis. Advanced-stage mycosis fungoides, defined as stages IIB to IV, requires systemic treatment and may include retinoids, interferon alfa, chemotherapy, targeted immunotherapy, and extracorporeal photochemotherapy6 (extracorporeal exposure of white blood cells to the photosensitizing agent psoralen, followed by UV-A irradiation and reinfusion of the treated cells).

Early-stage mycosis fungoides with limited skin and lymph node involvement (stages IA to IIA) has a 10-year survival rate of 70% to 90%. Patients with mycosis fungoides and tumor lesions are classified as having at least stage IIB disease, which is associated with a 10-year survival rate of 40%.7 Patients with stage IVB (visceral involvement) disease have a median survival of 1.4 years and a disease-specific survival of 18% at 5 years.8

Patient Outcome

A left axillary skin biopsy demonstrated a bandlike lymphoid infiltrate in the superficial dermis and epidermotropism, both characteristic of mycosis fungoides. Immunohistochemical staining of the biopsy specimen revealed CD4+/CD8– T cells and absence of normal CD7 T-cell antigens. The patient was diagnosed with stage IB mycosis fungoides, based on a whole-body PET scan that showed no enlarged lymph nodes and absence of Sézary cells in the peripheral blood. He underwent PUVA therapy 2 to 3 times weekly for 15 months, and his skin lesions gradually resolved. Repeat left axillary skin biopsy performed 15 months after initial presentation showed minimal lymphocytic infiltrate without evidence of epidermotropism or atypia. The patient has continued PUVA once weekly, and at his most recent clinic visit, 52 months after initial presentation, he had no cutaneous manifestations of mycosis fungoides.

Vestibular drop attacks diagnosed with valuable insights from CCTV

(8). Lucia Joffily et al , Published:August 24, 2024DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01589-, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(24)01589-7/fulltext

A 53-year-old man with a 2-year history of at least six episodes—three had been captured on CCTV (video)—when he suddenly collapsed without any warning signs and without losing consciousness, was referred to our neurotology service. The patient also reported that during one of the episodes he had fractured his right ankle. Additionally, for 3 years he had been having vertigo lasting more than 30 min, with tinnitus and some hearing loss in his left ear.

The patient reported that when the episodes occurred, he felt like he was being “pushed or pulled”.

The first episode happened in the newsagent, where he worked, whilst standing and serving a customer; the second in a cash and carry store as he searched for an item (figure 1); and the third in a mosque, as he was leaving. All attacks occurred without any precipitating factors; those captured on CCTV happened whilst standing, but he reported some episodes while seated and lying down. Witnesses reported that the patient had no change of colour, no abnormal movements, confusion, or other neurological signals prior to, or after the events. The patient had no other medical problems and was not prescribed any medication.

Previously, the patient’s general practitioner had done routine tests—full blood count, renal, liver, and thyroid function, glucose, and an electrocardiogram—which were within normal range. A neurologist had a telephone appointment with the patient because of the COVID-19 pandemic; an ear, nose, and throat surgeon did an audiogram which found a low frequency sensorineural hearing loss on the left, and conductive loss on the right, due to otosclerosis. CT head and MRI of the internal auditory meati, with contrast, prior to us seeing him, showed bilateral otosclerosis with no central pathology.

On examination, the patient was generally well; neurologically we found he had low-frequency sensorineural hearing loss on the left and, on the right, he had mixed loss, predominantly affecting the mid-range; he had left vestibular canal paresis on bithermal caloric test, and a normal video head impulse test.

A 4 h delayed-enhanced contrast MRI of the internal auditory meatuses showed confluent enlargement of the scala media, saccule and utricle (figure 2) on the left side—indicative of vestibular endolymphatic hydrops.

Considering the history, examination, and the imaging together, we made a diagnosis of Ménière’s disease—or Ménière’s syndrome—with vestibular drop attacks, or Tumarkin attacks. The patient was treated with intratympanic steroid injection on the left side and has, in 2 years of follow-up, had no further episodes.

Sudden attacks of loss of consciousness, altered levels of consciousness, dizziness and vertigo are common; episodes described as drop attacks include both falls and transient losses of consciousness. The most common causes are cardiovascular usually causing syncope or feeling lightheaded. Vertigo—a false or distorted sensation of motion, often felt even when the eyes are closed—is mostly seen in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, vestibular migraine, vestibular neuritis, and less frequently Ménière’s disease. In elderly patients both vestibular dysfunction and cardiac disorders may be present and contribute to such attacks. Epilepsy and functional neurological disorder need to be considered along with rarer causes of collapse—including cataplexy.

Ménière’s syndrome is characterised by recurrent vertigo, variable hearing loss, and tinnitus; Tumarkin attacks are seen in 6–7% of patients. The pathophysiology has yet to be elucidated but may be related to sudden changes in the otolith function of the utriculus and sacculus due to alterations in the pressure gradients within the inner ear. Patients may be unable to accurately describe the event, duration, level of consciousness, and muscle atonia of their attacks. Valuable insights into the onset, duration, and character of such events may be gleaned from CCTV—as in our case.

JAMA Cardiology Clinical Challenge: Tombstone Pattern Electrocardiogram in a Young Woman

(9). Yun Chen et al, JAMA Cardiol. Published online August 21, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2024.2537

Case report

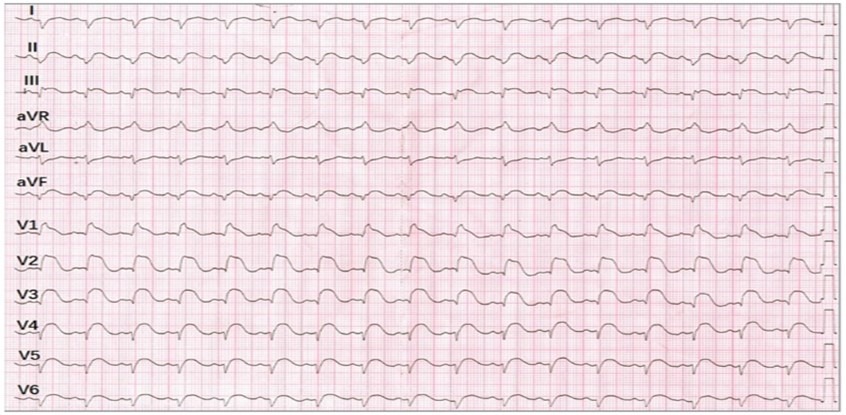

A woman in her mid-20s with no relevant medical history presented to the emergency department with a 2-day history of fever, chest pain, and exertional dyspnea. An initial electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus tachycardia, QRS widening (130 milliseconds), low-voltage complexes in the limb leads, and tomb stone like convex ST-segment elevation (STE) in most leads, particularly V1 through V6 (Figure 1). Transient second-degree atrioventricular block was observed on ambulatory ECG monitoring. Her blood pressure was 81/50 mm Hg. The N-terminal pro–brain-type natriuretic peptide was 10 099 pg/mL (to convert to ng/L, multiply by 1; reference value, <150) and the troponin I level was 22 ng/mL (to convert to µg/L, multiply by 1; reference value, <0.016). No obstructive stenosis was seen on coronary computed tomography angiography. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed symmetric left ventricular (LV) wall thickening (septal thickness, 16 mm) and reduced LV systolic function with an ejection fraction of 35%.Tombstone Pattern Electrocardiogram in a Young Woman.

Initial electrocardiogram demonstrating sinus tachycardia with ST-segment elevations of 1.0 mm in lead I; 2.0 mm in leads II, III, and the augmented vector foot (aVF); and 2.0 to 5.0 mm in the precordial leads. Widened QRS complexes and low-voltage complexes in the limb leads were observed. aVR indicates augmented vector right.

What Would You Do Next?

Emergent coronary angiography

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

Myocardial positron emission tomography

Endomyocardial biopsy

Diagnosis

Fulminant myocarditis

Discussion

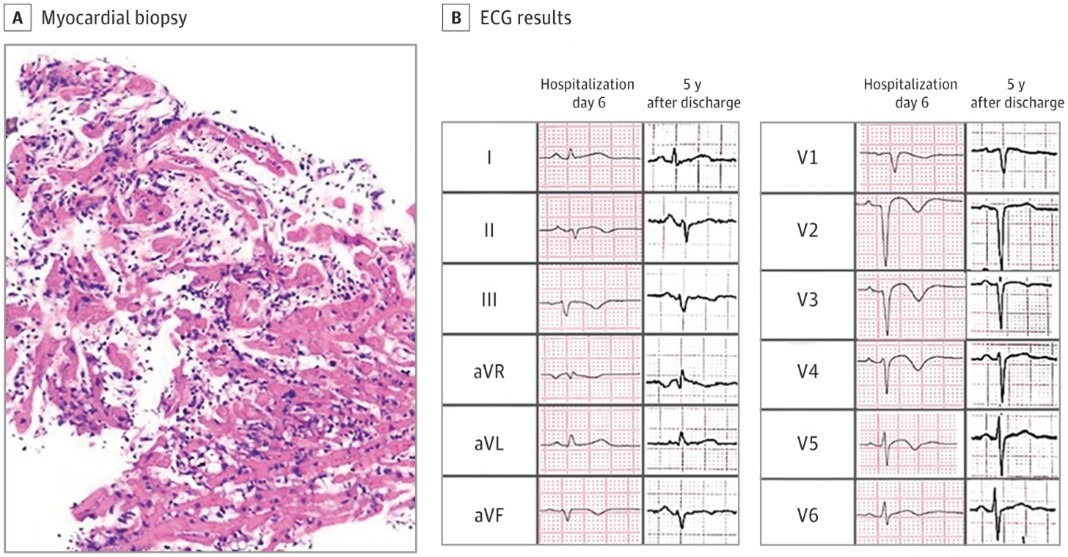

The diagnosis of fulminant myocarditis (FM) was confirmed subsequently by endomyocardial biopsy, which demonstrated extensive and diffuse lymphocytic infiltration, severe interstitial edema, and slightly myocyte necrosis (Figure 2A). Due to cardiogenic shock, an intra-aortic balloon pump was implemented soon after admission, combined with glucocorticoids and intravenous immunoglobulins. On the sixth day after admission, the intra-aortic balloon pump was removed, and a repeat ECG showed that the STE had decreased nearly to baseline, with diffuse T-wave inversion and Q waves in V1 to V3 (Figure 2B). Concomitantly, repeat ECG revealed that both LV wall thickness and LV ejection fraction were restored to the normal range. Subsequent cardiac magnetic imaging showed no late-gadolinium enhancement.

Myocardial biopsy and electrocardiogram (ECG) results. A, The pathologic findings included extensive and diffuse lymphocytic infiltration, severe interstitial edema, and mild myocyte necrosis. B, On day 6 following admission, ST-segment elevation had decreased nearly to baseline, with T-wave inversion in most leads and Q waves in V1 to V3. The 5-year follow-up ECG showed sinus rhythm with left anterior fascicular block; flat T waves in leads II, III, and augmented vector foot (AVF); and poor R-wave progression in leads V1 to V3. aVL indicates augmented vector left; aVR, augmented vector right.

FM represents the most acute and life-threatening manifestation of myocarditis, characterized by sudden onset and rapid clinical deterioration, with left and/or right ventricular dysfunction, refractory ventricular arrhythmias, and the need for pharmacological and/or mechanical circulatory support.1 In this patient, tombstonelike STE in extensive leads was indicative of severe myocardial injury. This is more commonly seen in ST-elevation myocardial infarction, but a diagnostic hallmark in FM is that there is no ST-segment depression in the reciprocal leads as would be seen in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Additionally, ST segments are elevated in lead augmented vector right in FM, while they are usually depressed in acute pericarditis.2 Lead augmented vector right has also been characterized in pericarditis or myocarditis by elevation of the PR interval. However, this change is often subtle in FM.2

The increased LV wall thickness in FM is due to the intense inflammatory response seen on endomyocardial biopsy. Interstitial edema contributes not only to the wall thickening, but also to the decreased ventricular contractility in this disorder.3 Therefore, the low-voltage complexes, QRS widening, and transient second-degree atrioventricular block in this patient were considered related to myocardial edema and inflammation, in line with the myocardial pathology. A QRS interval greater than 120 milliseconds on ECG emerged as an adverse prognostic factor associated with the long-term outcome of patients with FM.4 The patient was confirmed on endomyocardial biopsy to have lymphocytic myocarditis, which ruled out giant cell myocarditis and eosinophilic myocarditis and helped to guide an appropriately immunosuppressive treatment regimen. After effective immunotherapy, the myocardial thickness recovered, the relevant ECG indicators improved, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging also suggested resolution of the myocardial edema.

Patient Outcome

At 5-year follow-up after discharge, the patient felt well, and echocardiography revealed normal LV size, wall thickness, and ejection fraction. The ECG demonstrated sinus rhythm with left anterior fascicular blocks; flat T waves in leads II, III, and augmented vector foot, and poor R-wave progression in leads V1 to V3 (Figure 2B).

Postexercise Cardiac Asystole

(10). Yun-Tao Zhao et al, JAMA Intern Med. Published online August 26, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.1769

Case Presentation

Apatient in their 40s who received a diagnosis of hypertension but had no previous episodes of syncope or chest discomfort underwent an exercise treadmill test as part of a routine health assessment. The patient’s familial medical history, physical examination, baseline electrocardiogram (ECG), chest radiography, and biochemical analysis results were all within normal limits. The treadmill stress test, conducted using the standard Bruce protocol, saw the patient exercise for 12 minutes, reaching a peak heart rate of 158 beats per minute and a maximum systolic blood pressure of 176 mm Hg, which was indicative of a commendable functional capacity. The test concluded without any symptomatic manifestations, arrhythmias, or ST alterations (ST elevation >1.0 mm or ST depression >2 mm of horizontal or downsloping ST-segment depression).1

However, 6 minutes into the recovery phase, while the patient was seated and leaning forward, they exhibited presyncopal symptoms. The ECG changes captured by continuous ECG monitoring are shown in the Figure.

The 12-lead electrocardiogram illustrates the shift from a normal rhythm to sinus bradycardia, with a possible sinoatrial exit block along with junctional escapes and rhythm during the early postexercise recovery phase. The precordial leads (V1 through V6) capture the sinus bradycardia, with possible sinoatrial exit block and subsequent junctional escape rhythm during this recovery phase. Overall, this suggests sinus bradycardia with atrioventricular dissociation (short PR).

Questions: Based on the results of these ECGs, what is the diagnosis and the mechanism of arrhythmias?

Interpretation and Clinical Course

Immediate repositioning of the patient to a supine stance facilitated his swift recovery (3 minutes), with his heart rate stabilizing to its baseline value. A 12-lead ECG showed a sinus rhythm with a normal PR interval (160 ms) and narrow QRS complex (84 ms) with a normal corrected QT interval (438 ms). In the recovery phase, the patient became presyncopal. Continuous ECG monitoring captured a transition from sinus bradycardia, along with junctional escapes and rhythm (Figure). Overall, this suggested sinus bradycardia with atrioventricular dissociation (short PR). The patient was placed in a supine position and a few moments later recovered uneventfully. The patient’s heart rate returned to baseline. Subsequent echocardiographic analysis and coronary computed tomography angiography showed normal coronary arteries and normal left ventricular function, ruling out any structural cardiac anomalies or coronary artery issues. The final diagnosis was exercise-induced vasovagal sinus bradycardia, along with junctional escapes and rhythm.2 The patient was advised to avoid vigorous physical activity and, during a 6-month follow-up, remained symptom free without the need for medications or a pacemaker.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis for exercise-induced syncope is broad, encompassing structural heart disease (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, critical aortic stenosis), coronary artery disease (myocardial infarction), arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation, supraventricular tachycardias and ventricular tachycardias, including idiopathic and conditions predisposing to these rhythms, such as Brugada syndrome, long QT syndrome, and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia), and vasovagal syncope. The underlying pathophysiology of exercise-induced vasovagal syncope still remains unclear and requires further investigation, but it seems that the autonomic system plays a critical role. To keep up with oxygen consumption demands during exercise, heart rate and stroke volume rise, causing an increase in cardiac output. Muscular activity maintains this output because muscle contractions increase venous return (preload). In turn, cardiac contractility is increased because the greater volume of blood returned to the heart forces myocytes to expand farther, leading to a stronger ventricular contraction. For someone in an upright posture, the progressive reduction in venous return is accompanied by ventricular contractions against a diminishing ventricular volume, and ventricular mechanoreceptors are stimulated. Afferent vagal fibers transmit signals from the ventricular mechanoreceptors to the medulla, and reduced sympathetic tone induces hypotension, while increased parasympathetic overdrive produces sinus bradycardia, asystole, and possibly even atrioventricular block.2,3 Thus, excessive activation of parasympathetic tone may be a possible mechanism of asystole after exercise in this case. Such episodes typically manifest as near-fainting spells or actual unconsciousness, predominantly during the postexercise recuperation period.4

The optimal treatment strategy for patients with postexercise cardiac asystole is unknown. The treatment approach for these patients includes avoidance of strenuous exercise, pharmacological therapy, and permanent pacing. Owing to the few reported cases, the management has been empirical. Relatively asymptomatic patients experiencing syncope after strenuous exercise can be simply advised to avoid maximal exercise.2

Take-Home Points

- Vasovagal syncope is a common condition that is likely to be mediated by multiple mechanisms.

- Exercise-induced syncope requires systematic investigation to exclude structural heart disease, conduction system abnormalities, and noncardiac causes of syncope.

- Exercise-induced vasovagal syncope is rare but potentially dangerous.