Journal scan: A review of 10 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

From the desk of the Editor-in-chief

(1). Kristine T. Gapuz et al. Vitamin C–Induced Oxalate Nephropathy: An Underappreciated Consequence of Dietary Supplements. Annals of Internal Medicine: Clinical Cases. 2024;3(9).

Abstract

Oxalate nephropathy is an uncommon and often-missed cause of acute kidney injury. A careful history of medications, and especially dietary supplements, including vitamin C and turmeric, both of which can lead to renal deposition of oxalate, is essential to diagnosing this rare but potentially increasing cause of acute kidney injury. Here, we report a case of vitamin C–induced oxalate nephropathy leading to acute kidney injury requiring hemodialysis.

Oxalate nephropathy is an uncommon and often-missed cause of acute kidney injury (AKI) (1). Ingestion of oxalate-rich foods or dietary supplements converted to oxalate, such as vitamin C and turmeric, can lead to increased renal deposition of oxalate, resulting in nephrolithiasis, nephrocalcinosis, and oxalate nephropathy (1, 2). Here, we report a case of vitamin C–induced oxalate nephropathy leading to AKI that required hemodialysis.

Case Report

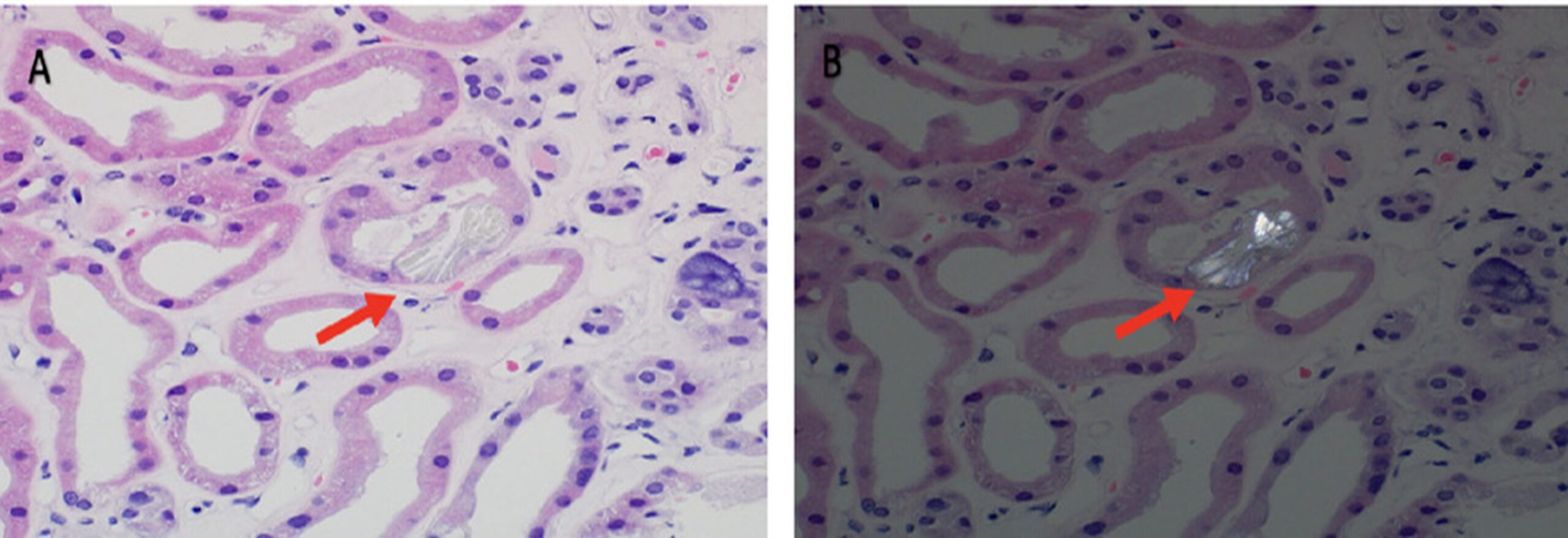

A 74-year-old man presented with a 2-week history of fluid overload and uremia, preceded by a viral-like illness. He was hypertensive, with decreased breath sounds, bilateral lower-extremity edema, asterixis, and severe cognitive impairment. Medical history was notable for well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus of 40 years’ duration, complicated by retinopathy and neuropathy. Laboratory study results revealed a creatinine level of 1432.4 mmol/L and a blood urea nitrogen level of 53.2 mmol/L. His baseline creatinine level 1 year previously was 1 mg/dL in the setting of subnephrotic diabetic glomerular disease. Hemoglobin A1c was 6.6%. Urinalysis showed proteinuria (>600 mg/dL), microscopic hematuria (26–50 erythrocytes/hpf), and pyuria (11–25 leukocytes/hpf). Spot urine yielded protein and albumin-to-creatinine ratios of 2605 mg/g and 1793 mg/g, respectively. Other than low-titer antinuclear antibody and antidouble-stranded DNA, serologic work-up was negative. An ultrasound scan of the retroperitoneum was unremarkable. Given uremia and anuric AKI, hemodialysis was initiated. A biopsy of the kidney was performed because of the rapidity of his AKI. Findings included diabetic nodular glomerulosclerosis in some glomeruli, with increased mesangial matrix and thickened glomerular basement membranes, approximately 50% interstitial fibrosis and tubular dropout, arterio- and arteriolosclerosis, and acute tubular injury with calcium oxalate deposits (Figure 1, A and B). Upon inquiry, the patient reported taking vitamin C, 2 g/day, for more than 30 years. Vitamin C and oxalate levels were not checked, as the biopsy results were not obtained until more than 1 week after admission. After a month, he demonstrated renal recovery, hemodialysis was stopped, and his creatinine level reached a plateau of 254.65 mmol/L.

Fig. (1). Left renal biopsy (hematoxylin–eosin stain; original magnification, × 400) showing calcium oxalate crystals (arrows) in the tubular lumen (A) and under polarized light (B).

A careful history of medications, and especially dietary supplements, including vitamin C and turmeric, both of which can lead to renal deposition of oxalate, is essential to diagnosing this rare but potentially increasing cause of AKI, given the recent trend toward dietary supplementation with vitamins and other health products. Measurement of levels of oxalate and vitamin C may help to increase suspicion for this entity.

(2). Ayumi Sugiura, et al. Spur-Cell Hemolytic Anemia. Annals of Internal Medicine: Clinical 2024;3(9).

Abstract

A woman was referred to our hospital for jaundice, subcutaneous bleeding, and anemia. Biopsy findings confirmed liver failure due to alcoholic cirrhosis. A peripheral-blood smear showed red blood cells with irregularly spaced spur-like projections, which indicated spur-cell hemolytic anemia. Spur-cell anemia is an acquired hemolytic anemia associated with liver cirrhosis. The condition is characterized by the increased presence of large red blood cells covered with spike-like projections that vary in width, length, and distribution. Despite the poor prognosis of spur-cell anemia, supportive measures have been effective for 9 months in this case in anticipation of a liver transplantation.

Case Report

A 52-year-old woman with an alcohol misuse disorder presented with subcutaneous bleeding in her lower leg, decreased coagulation factor activity (prothrombin time, 23%), and jaundice (total bilirubin, 222.3 µmol/L; direct bilirubin, 149.32 µmol/L). Blood tests revealed a total cholesterol level of 1.37 mmol/L, a high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level of 0.4138 mmol/L, a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level of 0.7500 mmol/L, a triglyceride level of 0.44 mmol/L, a total bile acid level of 456 μmol/L, an aspartate aminotransferase level of 0.75 µkat/L, an alanine aminotransferase level of 0.61 µkat/L, a lactate dehydrogenase level of 5.48 µkat/L, an alkaline phosphatase level of 8.85 µkat/L, and a gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase level of 0.38 µkat/L. A liver biopsy confirmed liver failure due to alcoholic cirrhosis (Figure 1, A), indicated by low serum albumin levels (23 g/L) and elevated Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer levels (15.2 COI). She had severe anemia (hemoglobin level, 67 g/L; reticulocyte count, 34 × 109/L) and an undetectable haptoglobin level (<50 mg/L), with a negative Coombs test. A peripheral blood smear showed red blood cells with spur-like projections (33.6%), indicating spur-cell hemolytic anemia (Figure 1, B). Her Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was 17 and Child-Pugh score was 13. She received symptomatic treatment, including blood transfusions and hepatoprotective therapy (tolvaptan, spironolactone, and furosemide for ascites; ursodeoxycholic acid and phenobarbital for jaundice and cholestasis; and branched-chain amino acid preparations and lactulose for hypoalbuminemia and hyperammonemia), over 9 months while awaiting a liver transplantation. Despite treatment, the number of spur cells did not significantly change.

Fig: A. Liver biopsy shows bridging fibrosis and the presence of regenerative nodules consisting of micronodular and macronodular mixed cirrhosis, which are compatible with alcoholic liver cirrhosis (Azan-Mallory staining). B. Peripheral blood smear shows red cells lacking central pallor with irregularly distributed surface projections (arrowheads), indicating the presence of spur cells. Spur cells accounted for 33.6% of all cells.

Discussion

Spur-cell hemolytic anemia cases often result in poor prognosis within weeks or months of hospitalization (1–3). While some cases with low spur cell counts still have a poor prognosis (4), the present patient has been receiving outpatient symptomatic treatment with complete abstinence from alcohol for 9 months, showing that prognosis cannot be based on spur cell count alone. Spur-cell hemolytic anemia can occur in both final and early end-stage cirrhosis patients and may respond to supportive measures until liver transplantation is possible.

(3). Jian Yang et al. Angioedema of the Intestines. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:941

A 53-year-old woman presented with a recurrent episode of severe, diffuse abdominal pain.

CT of the abdomen revealed segmental thickening of the walls of the colon and rectum and mesenteric edema.

(4). Flail Chest. A Zhi Hu et al, Published September 14, 2024

Abstract

A 59-year-old man was brought to the emergency department after a motor vehicle collision. Paradoxical movement of a segment of his chest wall during respiration was noted on examination

(5). Julia Hermann, et al. A Painless Right Anterior Neck Mass. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024;150(2):181-182. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2023.3953

Case Presentation

A 58-year-old woman presented with a several-week history of a painless right-sided swelling on her anterior neck. She denied trauma, recent illnesses, respiratory symptoms, dysphagia, oral lesions, hemoptysis, fever, fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats. She had an unremarkable medical history without history of hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, cancer, chemotherapy, radiation, or tuberculosis. She denied alcohol, tobacco, or current medication use. Her family history included a sibling with sarcoma in their 50s. On examination, a 4.0-cm mobile, nontender right lower anterior neck mass was palpated in a suprasternal location. No lymphadenopathy was noted. Laboratory results showed normal serum calcium levels and leukocyte counts.

Initial ultrasonography showed a 4.2-cm solid nodule adjacent to the lower pole of the right thyroid. Computed tomography results of the neck showed a 3.4-cm circumscribed, heterogenous, hypodense, enhancing mass that was abutting the inferior right thyroid and at the right lateral margin of the trachea. The mass was just medial to the right common carotid, causing left lateral displacement of the trachea

Fine-needle aspiration demonstrated many small round lymphocytes and a few groups of short bland spindle cells on hematoxylin-eosin staining. Immunohistochemical staining showed AE1/AE3–positive spindle cells and CD1a-, CD3-, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)–positive lymphocytes. The excised mass was a 4.8 × 4.0 × 3.2 cm yellow-tan, lobulated nodule with a smooth, firm cut surface, thin fibrous strands, and no hemorrhage, degeneration, or transcapsular invasion.

What Is Your Diagnosis?

- T lymphoblastic lymphoma

- Medullary thyroid cancer

- Parathyroid carcinoma

- Thymoma

Diagnosis

Thymoma

Discussion

Thymomas originate from thymic epithelial cells; therefore, most occur in the anterior mediastinum. However, 4% of all thymoma cases occur ectopically outside of the mediastinum. This extramediastinal location is explained by the embryological descent of the thymus, which arises in the neck during fetal development and descends along the cervical pathway to the mediastinum.1 Remnant thymic tissue along this path, commonly adjacent to the thyroid gland, has the potential for epithelial hyperplasia and development of thymoma. Middle-aged individuals are most affected by thymomas; however, ectopic thymomas are more common in prepubertal populations due to thymic involution.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography is a frequent first diagnostic study of choice. It provides insight into thymoma location, size, shape, and potential invasion into surrounding structures. For lesions abutting other mediastinal structures or irregular appearing lesions, magnetic resonance imaging can help to assist with preoperative planning. Diagnosis of a thymoma requires tissue confirmation either from definitive resection specimens or core needle biopsy. The World Health Organization histologic classification system aids in determining the potential behavior pattern of the tumor based on the degree of epithelial cellular atypia, as well as lymphocyte infiltration. The lymphocytic component consists of immature T cells, which are derived predominantly from the thymic cortex and can be targeted by CD3, CD1a, CD99, and TdT antibodies. However, these markers can also be present in T lymphoblastic lymphoma.5 Therefore, pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3), which stains the interconnected network of thymic epithelial cells but not T cells, is used to help distinguish thymomas from lymphoblastic lymphoma (Figure 2). The presence of B symptoms, which often accompany lymphoma, can also help distinguish thymoma, which usually has compressive symptoms alone.

The grading of thymomas is disputed; however, historically, the Masaoka-Koga and more recently the TNM staging systems are used The stages differ slightly between systems, but because metastatic spread to lymph nodes and other tissues is rare, both systems focus on the local invasive component of thymomas rather than tumor size or nodal involvement.6 In early-stage disease, the thymoma is well encapsulated, without invasion into the gland itself, while advancing stages demonstrate greater degrees of invasion beyond the capsule, up to and including direct invasion of adjacent mediastinal structures (aorta, superior vena cava, lung, pericardium). Additionally, all patients should be screened for the presence of myasthenia gravis, which is associated with approximately a third of thymoma cases. Although not directly a prognostic factor for survival, the presence of myasthenia gravis can potentially alter the conduct of the planned surgical intervention. Preoperative assessment includes review by anesthesia clinicians with respect to possible perioperative respiratory failure and the selective use of neuromuscular blockade.

Although thymomas may have an indolent course, they have malignant potential due to local invasion and the ability to metastasize.2 Thus, treatment for thymomas, regardless of size or invasion, should include surgical resection. Resection of the entire thymus and surrounding tissue is typically done to achieve the best prognostic outcome. This can include en-bloc resection and reconstruction of large surrounding vessels and the sacrifice of nerves, such as the phrenic nerve.7 In more advanced stages, multimodal approaches to therapy, including induction chemotherapy, adjuvant chemotherapy, and/or postoperative radiotherapy, may be required.3

Following treatment, the slow growth pattern necessitates extended imaging surveillance. The World Health Organization thymoma type is also an independent prognostic marker of recurrence-free survival but not overall survival.9 Current guidelines recommend a computed tomography scan every 6 months for the first 2 years followed by annual imaging for 10 years.4,10 The biannual screening timeline may be extended to 3 years in cases of advanced thymomas or if complete resection was not achieved.10

(6). Akash M. Bhat. Tracheal Chondrosarcoma—A Novel Presentation of Lynch Syndrome. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024;150(2):183-184. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2023.3908

Lynch syndrome is a hereditary cancer syndrome caused by germline variants in DNA mismatch repair genes, most commonly associated with colorectal and endometrial cancer Recent literature has also shown that Lynch syndrome may rarely manifest with sarcomas.1 To our knowledge, tracheal chondrosarcoma has never been reported as a manifestation of Lynch syndrome. Herein we demonstrate a unique case of a patient with regionally metastatic tracheal chondrosarcoma as a presentation of Lynch syndrome.

Case Presentation

A man in his 60s with no cancer history presented with 2 weeks of dysphagia, dysphonia, and a left neck mass. Family history included a parent with colon cancer and sister with uterine cancer. The patient had a prior normal colonoscopy findings. Imaging revealed a left tracheal mass involving the thyroid gland with bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy (Figure 1) and no distant metastases. Fine needle aspirate of the primary mass showed a low-grade chondroid neoplasm. The patient underwent hemithyroidectomy, resection of tracheal rings 2 to 5, and neck dissection, with pathologic analysis revealing a grade 2/3 chondrosarcoma involving 8 of 44 cervical lymph nodes. Intraoperative frozen specimen evaluation showed negative margins, but permanent specimen revealed a positive margin on the inferior tracheal ring. The patient was subsequently treated with adjuvant radiotherapy. Due to the rarity of the tumor, next-generation sequencing of the tumor with a 648 gene panel (Tempus Labs) was performed, which revealed a germline pathogenic MSH2 variant. The tumor was, however, microsatellite stable. Subsequent immunohistochemical staining of the tumor detected a loss of MSH2 and MSH6 proteins (Figure 2). Germline testing via an 88 gene panel (Tempus Labs) confirmed a heterozygous MSH2 c.1661 + 5G>C variant consistent with Lynch syndrome. The patient was subsequently referred for genetic counseling and colonoscopy

Histopathologic findings demonstrating loss of expression of MSH2 and MSH6, with intact MLH1 and PMS2 expression. Original magnification ×200 (all panels).

Coronal computed tomographic image with contrast of the tumor involving the tracheal wall (yellow line).

Discussion

Chondrosarcoma of the head and neck is a rare cancer, representing 0.1% of all head and neck malignant abnormalities. Tracheal chondrosarcomas are even rarer, with only 35 prior cases reported in the literature.2 The etiology of tracheal chondrosarcomas is theorized to be abnormal cartilage ossification and secondary chondroplasia from chronic inflammation. Metastasis is rare, with only 1 case having recurrent distant metastatic disease after initial surgical excision.

To our knowledge, this patient is the first documented case of a tracheal chondrosarcoma with a Lynch syndrome–associated variant. Osteosarcomas and soft tissue sarcomas have been observed in pathogenic MSH2 carriers, with incidence in patients with Lynch syndrome being more than 50 times and more than 1.8 times higher, respectively, than that of the regular population.1 One patient with chondrosarcoma and a germline MLH1 variant has been described, but the present patient is the first reported case with a germline MSH2 variant.

The consensus of current literature supports surgical excision with negative margins as optimal treatment. The role of adjuvant radiotherapy is unclear because chondrosarcomas are considered radioresistant owing to their slow growing nature. Adjuvant radiotherapy for tracheal chondrosarcoma has been reported in cases where surgical resection was incomplete or contraindicated. Although immune checkpoint inhibitors have not demonstrated efficacy in treating chondrosarcomas in general, pembrolizumab, a programmed cell death inhibitor, is approved for use in unresectable or metastatic mismatch repair deficient solid tumors. There is no data to support the use of adjuvant pembrolizumab after resection and radiation therapy, but this patient would be an appropriate candidate for pembrolizumab therapy for recurrent disease.

We present a unique case of regionally metastatic tracheal chondrosarcoma associated with Lynch syndrome. The incidental discovery of Lynch syndrome has significant clinical implications for the patient and his family. This case displays the increased risk for tumorigenesis of all types in patients with germline variants in DNA mismatch repair genes and highlights the importance of using advanced genetic testing (ie, next-generation sequencing) to identify important therapeutic options in patients with rare tumors.

(7). Aarti Bansal et al. Optimising inhaled therapy for patients with asthma. BMJ 2024; 386 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2024-080353.

What you need to know

Sub-optimally controlled asthma is common, in part because of normalisation of symptoms, underuse of preventer therapy, overuse of reliever therapy, and poor inhaler technique. Ensuring patients are using the right inhaled medicine and that this is getting to the right place in the airways is critical to improving asthma control

Right inhaled medicine: Adherence to inhaled corticosteroid preventer therapy can be encouraged by explaining the role of airway inflammation in causing asthma symptoms and considering the use of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)-formoterol combination inhaler regimens

Right place: Ensure patients have the most appropriate inhaler device type, based on their inhaler technique and preferences, which will maximise the likelihood that medication reaches their airways

Asthma is one of the most common non-communicable diseases and carries a substantial morbidity and mortality burden worldwide.1 A cross-sectional study from 17 countries carried out by the Global Asthma Network in 2022 found that about 7% of adults were affected by asthma symptoms that were not well controlled, resulting in a high burden of preventable symptoms, restrictions on activity, and an increased risk of asthma attacks

(8). Chang Kai-Chun et al. Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography. ST-Segment Elevation in a Woman with Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. JAMA Intern Med. Published online September 16, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.2886

Case Presentation

A woman in her mid 70s presented to the emergency department following a sudden loss of consciousness during a meal. When paramedics arrived, the patient had a palpable pulse, but an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) developed in the ambulance. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was initiated, achieving return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after 19 minutes without a shockable rhythm. The reported medical history included hypertension. The patient underwent an electrocardiogram (ECG) on arrival (Figure, A).

A, The ECG of the patient on arrival in the emergency department revealed atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rhythm at a rate around 140 to 150 beats per minute. The ST segment was remarkable for convex ST elevation across lateral leads (V4 through V6, I, aVL) with fusion of QRS complex. B, There are shark-fin sign over leads I and aVL and lambda wave over leads V4 through V6, showing merged R wave and elevated ST segment.

Questions: What are the ECG findings? How can these findings be interpreted in the given clinical context?

Interpretation

The ECG revealed irregular, narrow atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rhythm at a rate around 140 to 150 beats per minute. The ST segment was remarkable for convex ST elevation across lateral leads (V4 through V6, I, aVL) with fusion of QRS complex, which formed a triangular morphology known as the same configuration called shark-fin phenomenon and lambda-wave pattern (Figure, B). ST depression in leads II, III, and aVF was considered a reciprocal change of leads I and aVL. Precordial leads V1 through V2 also had marked ST depression, which may indicate posterior leads ST elevation.

Clinical Course

In the emergency department, follow-up ECG showed persistent shark-fin phenomenon. Echocardiography revealed preserved left ventricular ejection fraction without regional wall motion abnormalities. Laboratory analysis indicated mixed metabolic and respiratory acidosis (pH: 7.14, PaCO2: 68 mm Hg, HCO3: 22.4 mmol/L, base excess: −6.7 mEq/L [to convert to mmol/L, multiply by 1], lactic acid: 5.37 mmol/L) without hyperkalemia (potassium: 3.54 mEq/L [to convert to mmol/L, multiply by 1]). Cardiac biomarkers were nearly normal (troponin T: 15.91 ng/L [to convert to µg/L, multiply by 1], N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide: 100.5 pg/mL [to convert to ng/L, multiply by 1]). Due to unconsciousness, an emergent CT was arranged and revealed diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage without myocardial hypo-enhancement, pulmonary embolism, or pneumothorax. Subarachnoid hemorrhage–related ST-T changes were favored so coronary angiogram was not performed. The patient was admitted to the neurological intensive care unit. Due to poor prognosis, the family opted for palliative care. The patient passed away on the second day of admission.

Discussion

This case presented an ST-segment elevation with a unique presentation of the giant R waves (amplitude ≥1 mV) that merged with markedly elevated ST segments, which formed a triangular morphology, the so-called shark-fin sign, giant R wave, triangular QRS-ST-T waveform, or lambda-wave pattern. The shark-fin sign is associated with poor outcome in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). However, the patient experienced acute-onset consciousness loss without evidence of chest discomfort or shockable rhythm, and echocardiography revealed no evidence of regional wall motion abnormality. ST-segment elevation with cause other than myocardial infarction was suspected and was later confirmed to be subarachnoid hemorrhage related.

The ST-segment elevation raised concerns about acute coronary syndrome (ACS). ACS is the leading cause of OHCA, and guidelines recommend a primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) strategy for patients with ROSC and persistent ST-segment elevation.1 Nevertheless, other potential causes should be considered within the clinical context. The differential diagnosis for ST-segment elevation in a patient with cardiac arrest encompasses benign early repolarization, acute myopericarditis, stress cardiomyopathy, Brugada syndrome, pulmonary embolism, hyperkalemia, left bundle branch block, left ventricular aneurysm, or intracranial hemorrhage.

The shark-fin sign was first characterized by Ekmekci et al2 in 1961 and was later reported to be found in patients with STEMI, takotsubo cardiomyopathy, and type 2 myocardial infarction from coronary spasm and hemorrhagic shock. In patients with STEMI presenting with shark-fin sign, the sign was usually associated with a large area of myocardial ischemia from occluded left main or proximal left anterior descending arteries. Recent studies revealed shark-fin sign in STEMI as a predictor of high risk of cardiogenic shock, ventricular fibrillation, and in-hospital mortality and was reported to present in 1.9% of all patients with STEMI in a study group.3 The mechanism of R wave merging with the down-sloping ST segment remained unclear and was speculated to be associated with the significant slowing of transmural electrical conduction, due to biochemical and ion concentration changes during large areas of myocardial injury.4

To our knowledge, it was the first case of shark-fin sign with the cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage. The association between intracranial hemorrhage and ECG changes is well documented, with investigations suggesting sympathetic overstimulation as the possible underlying mechanism. ECG changes observed in intracranial hemorrhage include the presence of U waves, T wave abnormalities, QTc prolongation, high R wave, ST depression, and bradycardia.5

In cases where intracranial hemorrhage leads to OHCA with concurrent ST-segment elevation, opting for a PPCI strategy may exacerbate the hemorrhage and compromise the patient’s prognosis. This case underscores the significance of meticulous clinical assessment for ST-segment changes and the inclusion of intracranial pathology in the differential diagnosis. Clinical clues that suggest intracranial pathology in the context of ST-segment changes encompass the absence of chest pain before events, abrupt consciousness changes without recovery, the absence of a shockable rhythm during CPR, and incompatible LV regional wall motions of echocardiography results.

Take-Home Points

In patients presenting OHCA with ROSC and a persistent ST-segment elevation, differential diagnosis other than acute myocardial infarction should be kept in mind and measurements need to be excluded.

The shark-fin phenomenon is mostly associated with myocardial infarction or takotsubo cardiomyopathy but could be rarely found in intracranial hemorrhage. ECG changes in intracranial hemorrhage could mimic lots of ECG changes in ACS.

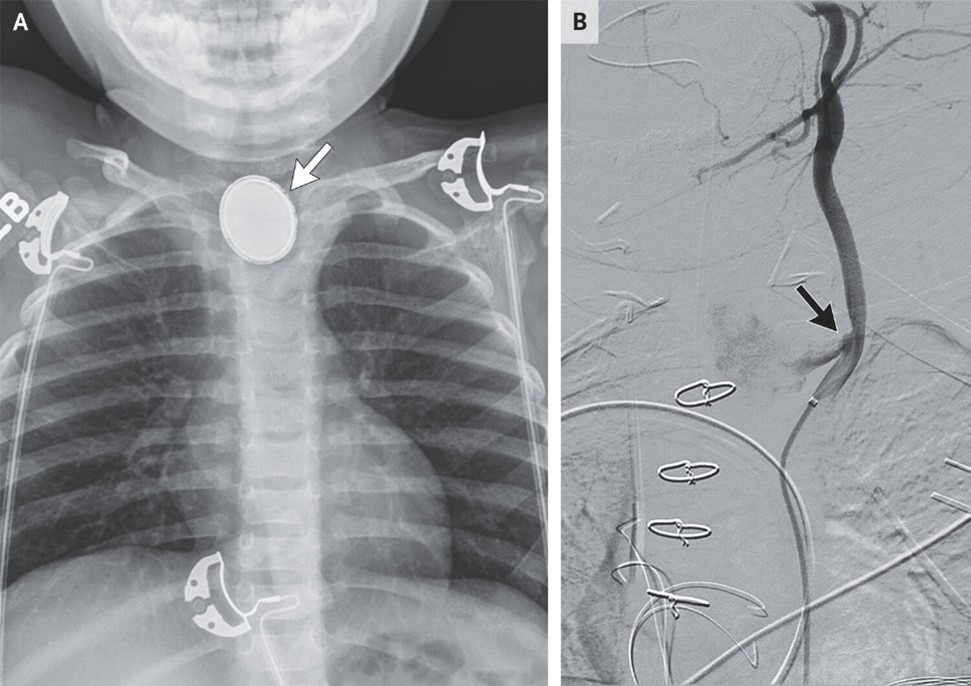

(8). Miriam R. Smetak, et al. Button-Battery Ingestion. N Engl J Med 2024;391:1139. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMicm2310606

Abstract

An 11-month-old girl presented with a 2-week history of progressive dysphagia and cough. A chest radiograph showed a foreign body with a “double-ring” sign. Torrential hematemesis subsequently developed.

(9). Dominic Franceschelli. Rerupture of an Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. 2024,DOI: 10.1056/NEJMicm2309209

Abstract

A woman was transferred to a specialty hospital for endovascular treatment of a ruptured intracranial aneurysm that led to a subarachnoid hemorrhage. During intraoperative angiography, the aneurysm reruptured.

(10). Jacqui Wise. A third of patients miss out on risk assessments before surgery. BMJ 2024; 386 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.q2035.

Almost one in three patients having major non-cardiac surgery still do not receive a documented individualised risk assessment, research by the Royal College of Anaesthetists has found.1 The proportion has remained unchanged since the college’s perioperative quality improvement programme (PQIP) began in 2016, which it says “represents a real opportunity for improvement.”

The latest cycle of PQIP included 8634 patients who had major surgery between March 2023 and March 2024, from 135 hospitals across the UK. Comparisons were also made with earlier cohorts, making a total of 53 478 patients at 173 hospitals

Individualised risk assessments help identify existing conditions that may cause surgical complications and enable doctors to plan care tailored to the patient. They also improve shared decision making between clinicians and patient.