Multiple Sclerosis: An overview

Bhuvaneswari Rajendran

Consultant Neurologist and Neuroelectrophysiologist, Kauvery Hospital, Chennai, India

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory condition that causes demyelination and axonal loss in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord).

The primary brain insult- Sclerosis, and its clinical sequelae are ‘disseminated in space’, affecting different anatomical sites, and ‘disseminated in time’, appearing episodically over time.

It could have an auto-immune basis but real aetiology is not clear. Environmental factors and genetics do play a role but there is still a lot of ambiguity on the interplay of these factors. Vitamin D deficiency seems to have an influence on the severity of the disease process and thus correction and supplementation is recommended for MS patients.

Prevalence

Multiple sclerosis has a predilection for young females, with a ratio of 3:1. It is usually seen between 20-40 years of age.

However late or early presentations can be encountered and almost 10% of cases have onset before 18 years.

MS in general demonstrates a prevalence based on latitude, with increased prevalence in northern latitudes of Europe and North America.

Various studies have noted that populations that migrate to areas of greater MS prevalence during childhood also acquire a higher risk of acquiring MS. Other studies have called this observation into question.

In India, visuo-spinal variant was more commonly reported initially and MS was considered rare. But we are now seeing more patients with various other manifestations including brain stem and cerebral involvement.

MS exists in India, although its prevalence is lower than among European and American populations. The phenotypic presentation of MS in India seems quite similar to the West, and it has also been observed that some of the genes in Indian patients are similar to those seen in the Western patient population. Large epidemiological studies are needed to study MS incidence and prevalence in India.

ICMR has recently launched a registry for MS patients in the country and hopefully this shall help us understand the Indian pattern better.

Types

The sub-division of MS as relapsing and remitting type (RRMS), secondary progressive MS (SPMS) and primary progressive MS (PPMS) is based more on clinical characteristics and not specific biologic pathophysiology. Nonetheless, they provide an organized framework for diagnosis and long-term management.

Relapsing and remitting type is the most common and represents clearly the spatial and temporal framework of MS presentation in general. Our available disease-modifying drugs are most effective against this type and helps prevent new lesion formation.

There are a few rare types of MS described such as:

(1) Marburg type: This type has a fulminant monophasic course in most cases, with poor response to treatment.

(2) Balo type: By definition shows a peculiar pattern of pathology in cerebral hemispheric white matter consisting of a concentric, mosaic, or floral configuration of alternating bands of white matter whose basis is relatively preserved myelination alternating with regions of demyelination.

(3) Schilder’s disease: This is an acute MS that occurs in childhood with widespread white matter involvement. The clinical course is diverse.

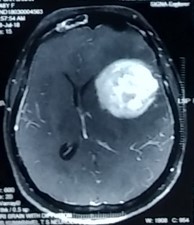

(4) Tumefactive MS (TMS): Rarely the plaque size can be >= 2 cm with mass effect, edema, or ring enhancement on magnetic resonance, features pointing to a tumour-like space-occupying lesion.

Clinical Presentation

The presentation of MS depends on the locations of the multifocal lesions in the CNS. The severity of symptoms is reflective of lesion burden, location, and degree of tissue injury. The common manifestations include

- Vision symptom: includes vision loss (either monocular or homonymous), double vision, symptoms relating to optic neuritis or other cranial neuropathies

- Vestibular symptoms: vertigo, gait imbalance

- Bulbar dysfunction: dysarthria, dysphagia

- Motor: weakness, tremor, spasticity, fatigue

- Sensory: loss of sensation, paresthesias, dysesthesias

If spinal cord is involved then symptoms include

- Mobility problems, imbalance,

- Urinary and bowel symptoms: incontinence, retention, urgency, constipation, diarrhoea, reflux

The RR course of MS is observed in a majority of patients and is characterized by exacerbation and relapses of neurological symptoms, with stability between episodes. The following features generally characterize the RR course of MS:

- New or recurrent neurological symptoms

- Symptoms developing over days and weeks

- Symptoms lasting 24 to 48 h

Symptoms from relapses frequently resolve. However, over time, residual symptoms relating to episodes of exacerbation occur.

The secondary-progressive (SP) course is often noted in patients with RR after a few years of onset and is characterized by a more gradual worsening of symptoms with continued progression with or without superimposed relapses in some patients.

A small proportion of patients demonstrate gradual worsening of disability from onset of disease, described as the primary progressive (PP) course of MS. Myelopathy, cognitive symptoms, and visual symptoms are most frequently the clinical manifestations in this clinical course.

Evaluation

No single pathognomonic test exists for the diagnosis of MS. There are no definitive bio-markers too.

Diagnosis is made by weighing the history and physical examination. In addition, laboratory tests are used such as

- MRI brain and spine with contrast

- Evoked potentials especially visual evoked potentials

- CSF studies mainly looking for Oligo-clonal bands.

- Bloods, to exclude other causes of the patient’s symptoms.

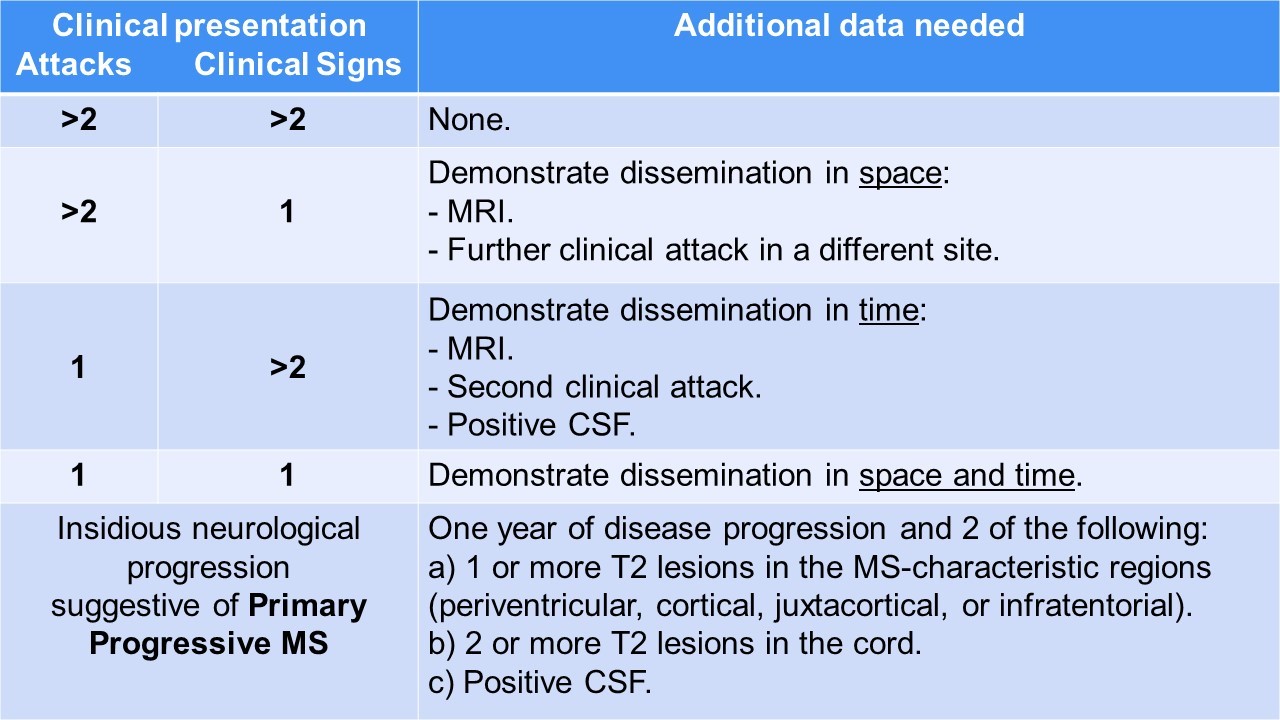

Clinically a diagnosis can be made with evidence of two or more relapses: this is possible through objective clinical evidence of two or more lesions or objective clinical evidence of one lesion with reliable historical evidence of a prior relapse. Dissemination in space (DIS) and dissemination in time (DIT) are two hallmarks of the accurate diagnosis of MS. DIS is assessed using information from the history and physical and understanding in determining the location of CNS involvement.

The 2010 McDonald’s criteria, later revised in 2017, combines these factors and are used world-wide for the diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis.

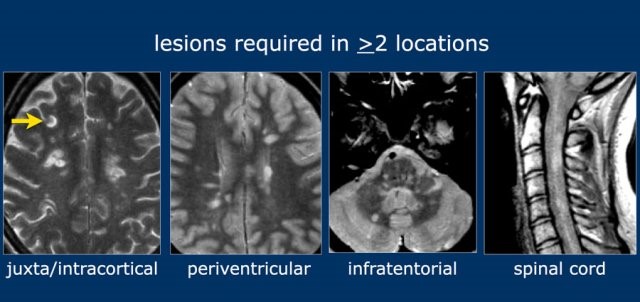

The chief characteristics of MS lesions on MRI can be summarized as the following:

- Lesions are T2 hyperintense, T1 isointense/hypointense.

- Lesions are classically oval or can be patchy.

- A high predilection for periventricular white matter

- Lesions are perpendicular to the ependymal surface (Dawson’s fingers)

- Gadolinium enhancement with active lesions noted as classically diffuse or rim enhancement.

- Thinning of the corpus callosum and parenchymal atrophy

- Cord lesions classically involve the cervical or thoracic cord

The classic abnormal CSF findings in MS are as follows:

- Elevated protein and elevated myelin basic protein

- Leukocytes (occasionally seen, and typically mononuclear cells)

- Increased total IgG, increased free kappa light chains, oligoclonal bands

Specific blood studies to include CBC, TSH, vitamin B12, sedimentation rate, and ANA should also be obtained in all patients.

Blood Aquaporin (NMO) antibodies and Anti MOG ( myelin ) antibodies are also checked to rule out NMSOD as this inflammatory condition is slightly more common in the Indian population.

Fig. 1. Multiple typical demyelination lesions in brain and spine.

Fig. 1. Multiple typical demyelination lesions in brain and spine.

Fig. 2. Showing evidence for Tumefactive MS.

Fig. 2. Showing evidence for Tumefactive MS.

Table 1. 2017 Mc Donald ‘s criteria for Dissemination of time and Space

Treatment/Management

Acute attacks are always treated with high dose steroids, initially given intravenously and then changed to oral route, and tapered over time. This is common to treatment of the NMSOD group too.

For prevention of new lesions, disease-modifying therapies are the mainstay of treatment of relapsing-remitting MS. Early treatment should commence upon establishing a diagnosis of MS. Short term goal includes a reduction in MRI lesion activity. Long term goals include prevention of secondary progressive MS. The primary issues after initiating therapy include patient compliance, costs of treatment and monitoring for drug toxicity.

In India, considering the cost of treatment, compliance is a challenge and as physicians, we need to reiterate the importance of continuation of long-term treatment.

Oral drugs although taken every day are slightly cheaper in terms of monthly expense. Following are the commonly used medications.

The commonly used IV medications include:

- Glatiramer acetate: This medication may help block the immune system’s attack on myelin and must be injected beneath the skin. Side effects may include skin irritation at the injection site.

- Interferon-beta preparations have various mechanisms of possible action. Interferon-beta modulates T, and B-cell function, and possibly alters cytokine expression, plays a role in blood-brain barrier recovery, and potentially decreases matrix metalloproteinase expression. Administration is either subcutaneous or intramuscular, depending on the preparation. Side effects include flu-like symptoms.

- Natalizumab is an intravenously administered humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks leukocyte adhesion with vascular endothelial cells. This drug inhibits leukocyte migration into the central nervous system. Natalizumab is usually well tolerated. Mild headaches and flushing often occur during intravenous administration.

- Alemtuzumab, already approved for the treatment of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, is a monoclonal antibody directed against the CD52 antigen, leading to a profound depletion of circulating lymphocytes. Phase II28 and phase III trials29,30 showed a consistent efficacy of this compound in reducing anti-inflammatory activity, shown by both clinical and MRI outcomes in both MS patients naive to treatments and those who had not responded to glatiramer acetate or interferon-β.

- Ocrelizumab is used to treat active relapsing MS or early primary progressive MS. t is a humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody.[4] It targets CD20 marker on B lymphocytes and hence is an immunosuppressive drug

In India, Beta interferon therapies and Natalizumab are easily available and most commonly used.

Oral treatments include:

- Fingolimod. This once-daily oral medication reduces relapse rate. Side effects include Cardiac arrythmias, blood pressure variations, infections, headaches and blurred vision.

- Dimethyl fumarate. This twice-daily oral medication can reduce relapses. Side effects may include flushing, diarrhea, nausea and lowered white blood cell count. This drug requires blood test monitoring on a regular basis.

- Teriflunomide. This once-daily oral medication can reduce relapse rate. Teriflunomide can cause liver damage, hair loss and other side effects. This drug is associated with birth defects when taken by both men and women. Therefore, use contraception when taking this medication and for up to two years afterward. Couples who wish to become pregnant should talk to their doctor about ways to speed elimination of the drug from the body. This drug requires blood test monitoring in a regular basis.

- Cladribine. This medication is generally prescribed as second line treatment for those with relapsing-remitting MS. It was also approved for secondary-progressive MS. It is given in two treatment courses, spread over a two-week period, over the course of two years. Side effects include upper respiratory infections, headaches, tumours, serious infections and reduced levels of white blood cells.

In India, Dimethyl Fumarate and Teriflunomide are mostly commonly used. In fact, oral drugs preferred by patients as they are most cost effective on long-term basis.

Rituximab (RTX)

An increasing body of evidence supports the high efficacy and the low drug discontinuation rate of B-cell-depleting anti-CD20-antibody RTX for the treatment of MS.

Long-term observation of RTX therapy in RA and in NMOSD suggests that RTX is highly effective, safe and well tolerated. There is also some evidence for the use RTX in primary progressive type of MS.

There are many more drugs available outside this list but this paper includes only those most commonly used in India and with maximum evidence for efficacy.

Patients with either secondary progressive MS or primary progressive MS appear to represent primarily neurodegenerative processes. Disease-modifying therapies are, therefore, less effective, and treatment with these therapies has ranged from possible benefit to little effect on disease progression.

In March 2017, ocrelizumab was approved in the United States for the treatment of primary progressive multiple sclerosis in adults and active secondary progressive disease in adults.

Differential Diagnosis

Other demyelinating or inflammatory CNS syndromes: Examples include optic neuritis, Marburg disease, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, Devic neuromyelitis optica, and partial transverse myelitis.

- General inflammatory and autoimmune syndromes. Examples include systemic lupus erythematosus, Wegener granulomatosis, sarcoidosis, and Sjogren syndrome.

- Infectious aetiologies such as Lyme disease, syphilis, HIV, and herpes viruses

- Vascular aetiologies such as migraine headaches, small vessel ischemia, vascular malformations and emboli

- Metabolic causes that include vitamin deficiencies including B12 and thyroid disease

- Uncommon genetic aetiologies that include mitochondrial cytopathy, Fabry disease, Alexander disease, hereditary spastic paraplegia

- Neoplastic causes that include primary CNS malignancies or metastasis

Prognosis

The prognosis and severity of the disease vary between patients. The condition is often mild early on in the disease and worsens as time progresses.

Factors that suggest a worse prognosis include:

- Male gender

- Progressive course

- Primarily pyramidal or cerebellar symptoms

- More frequent relapses

- Minimal recovery between relapses

- Multifocal onset

- High early relapse rate

- Large lesion load and brain atrophy on MRI

Complications

The long-term disability of MS reflects an accumulation of symptoms from each successive incomplete recovery from relapse.

- Impaired mobility occurs in a majority of patients with long term MS.

- Chronic dysphagia from bulbar dysfunction can be a source of chronic aspiration.

- Urinary tract infections from bladder dysfunction

- Constipation is the most frequent gastrointestinal complication

- Erectile dysfunction

- Cognitive impairment, mood disorders, and generalized fatigue are known long term sources of morbidity.

Multi-disciplinary approach

MS is a complex neurologic disorder that results in both neurologic and non-neurologic symptoms, disability, and complaints. Other specialities are also involved in the care.

- Neuro-ophthalmology

- Psychiatry/ cognitive psychology

- Pain management

- Nursing/physician assistants

- Speech therapy

- Occupational therapy

- Social work

- Physical medicine and rehabilitation

- Urology (in the setting of genitourinary complications)

- Gastroenterology (in the setting of gastrointestinal complications)

Conclusion

A diagnosis of MS can be difficult for a patient, and the doctor plays a supportive role in counselling the patient about the diagnosis. Predicting disease course is difficult, and a provider should educate the patient on the wide range of possibilities in disease progression. Clinicians should emphasize that patients often do well and explain the role of effective medications on disease treatment. Patients should know to contact their provider if they experience new neurologic symptoms. There should be a lot of emphasis on lifestyle, exercise, habits, Vitamin D supplementation, a balanced diet. Patients should also be counselled on the importance of compliance with disease-modifying therapy, considering the side-effect profile of these medications. In India, as the cost of treatment is so high, when the patient is well for considerable duration, there is a general tendency to stop medication and follow up. As doctors, we need to keep counselling and checking on these patients to make sure that they do not end with severe complications or secondary progression on sudden with-drawl of treatment.

References

[1]. McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:121-127.

[2]. Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:162-173.

[3]. Filippi M, Rocca MA, Ciccarelli O, et al. On behalf of the MAGNIMS study group. MRI criteria for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: MAGNIMS concensus guidelines. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:292-303.

[4]. Valk J, van der Knaap MS (1995) Multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica, concentric sclerosis, and Schilder’s diffuse sclerosis. In: Magnetic resonance of myelin, myelination,and myelin disorders. Springer-Verlag, Berlin-Heidelberg-New York, 1995;179-205.

[5]. Simon JH, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Variants of multiple sclerosis, Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2008;18(4):703-716.

[6]. Milligan NM, Newcombe R, Compston DA. A double-blind controlled trial of high dose methylprednisolone in patients with multiple sclerosis: 1. Clinical effects. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1987;50:511-516.

[7]. Noyes K, Weinstock-Guttman B. Impact of diagnosis and early treatment on the course of multiple sclerosis. Am J Manag Care. 2013 Nov;19(17 Suppl):s321-31.

[8]. University of California, San Francisco MS-EPIC Team: Cree BA, Gourraud PA, Oksenberg JR, Bevan C, Crabtree-Hartman E, Gelfand JM, Goodin DS, Graves J, Green AJ, Mowry E, Okuda DT, Pelletier D, von Büdingen HC, Zamvil SS, Agrawal A, Caillier S, Ciocca C, Gomez R, Kanner R, Lincoln R, Lizee A, Qualley P, Santaniello A, Suleiman L, Bucci M, Panara V, Papinutto N, Stern WA, Zhu AH, Cutter GR, Baranzini S, Henry RG, Hauser SL. Long-term evolution of multiple sclerosis disability in the treatment era. Ann Neurol. 2016 Oct;80(4):499-510.

[9]. Ntranos A, Lublin F. Diagnostic Criteria, Classification and Treatment Goals in Multiple Sclerosis: The Chronicles of Time and Space. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016 Oct;16(10):90.

[10]. Tsunoda I, Fujinami RS. Inside-Out versus Outside-In models for virus induced demyelination: axonal damage triggering demyelination. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2002;24(2):105-25.

[11]. Simpson S, Blizzard L, Otahal P, Van der Mei I, Taylor B. Latitude is significantly associated with the prevalence of multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011 Oct;82(10):1132-41.

[12]. Sintzel MB, Rametta M, Reder AT. Vitamin D and Multiple Sclerosis: A Comprehensive Review. Neurol Ther. 2018 Jun;7(1):59-85.

[13]. Guan Y, Jakimovski D, Ramanathan M, Weinstock-Guttman B, Zivadinov R. The role of Epstein-Barr virus in multiple sclerosis: from molecular pathophysiology to in vivo imaging. Neural Regen Res. 2019 Mar;14(3):373-386.

[14]. Zipp F, Oh J, Fragoso YD, Waubant E. Implementing the 2017 McDonald criteria for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019 Aug;15(8):441-445.

[15]. Lalive PH, Neuhaus O, Benkhoucha M, Burger D, Hohlfeld R, Zamvil SS, Weber MS. Glatiramer acetate in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: emerging concepts regarding its mechanism of action. CNS Drugs. 2011 May;25(5):401-14.

[16]. Wehner NG, Gasper C, Shopp G, Nelson J, Draper K, Parker S, Clarke J. Immunotoxicity profile of natalizumab. J Immunotoxicol. 2009 Jun;6(2):115-29.

[17]. Bergamaschi R. Prognostic factors in multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;79:423-47.

[18]. Singh B, Isaiah P, Chandy J. Multiple sclerosis (studies on sixteen cases) Neurology. 1954;1:49-59.

[19]. Bharucha EP, Umarji RM. Disseminated sclerosis in India. Int J Neurol. 1961;2:182-8.

[20]. Singhal BS. Multiple sclerosis – Indian experience. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1985;14:32-6.

[21]. Multiple Sclerosis international Federation, Atlas of MS. 2013. [Last accessed on 2015 Jul 4]. www.msif.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Atlas-of-MS.pdf .

[22]. Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, Cutter GR, Sí¸rensen PS, Thompson AJ, Wolinsky JS, Balcer LJ, Banwell B, Barkhof F, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83:278-286.

[23]. Carrithers MD. Update on disease-modifying treatments for multiple sclerosis. Clin Ther. 2014;36:1938-1945.

[24]. Wingerchuk DM, Carter JL. Multiple sclerosis: current and emerging disease-modifying therapies and treatment strategies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:225-240.

[25]. Weinstock-Guttman B. An update on new and emerging therapies for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19:s343-s354.

[26]. Sormani MP, Li DK, Bruzzi P, Stubinski B, Cornelisse P, Rocak S, De Stefano N. Combined MRI lesions and relapses as a surrogate for disability in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2011;77:1684-1690.

[27]. Pecori C, Giannini M, Portaccio E, Ghezzi A, Hakiki B, Pastí² L, Razzolini L, Sturchio A, De Giglio L, Pozzilli C, Paolicelli D, Trojano M, Marrosu MG, Patti F, Mancardi GL, Solaro C, Totaro R, Tola MR, De Luca G, Lugaresi A, Moiola L, Martinelli V, Comi G, Amato MP. Paternal therapy with disease modifying drugs in multiple sclerosis and pregnancy outcomes: a prospective observational multicentric study. BMC Neurol 2014; 14: 114 [PMID: 24884599 DOI: 10.1186/1471-2377-14-114]

[28]. Hauser SL, Waubant E, Arnold DL, Vollmer T, Antel J, Fox RJ, Bar-Or A, Panzara M, Sarkar N, Agarwal S, Langer-Gould A, Smith CH, HERMES Trial Group (2008) B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 358(7):676-688. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0706383 32.

[29]. Hawker K, O’Connor P, Freedman MS, Calabresi PA, Antel J, Simon J, Hauser S, Waubant E, Vollmer T, Panitch H, Zhang J, Chin P, Smith CH, OLYMPUS trial group (2009) Rituximab in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis: results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Ann Neurol 66(4):460-471. https://doi.org/10.1002/ ana.21867 38.