Postpartum Ischemic Stroke

Monisha1, Gayathri2

1PG Diploma in Anesthesiology, Kauvery Hospital Hosur

2Senior Consultant – Anaesthesia, Kauvery Hospital Hosur

Abstract

Stroke is a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. The incidence of stroke in women during pregnancy and the postpartum period is approximately triple the incidence of stroke in non-pregnant women of similar age.1

The majority of maternal strokes occur postpartum, often after discharge home following delivery, the median time to readmission for stroke after delivery was 8 days 1, and up to half are hemorrhagic strokes.

Migraine and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, are important risk factors for maternal stroke. Physiological changes of pregnancy including venous stasis, hypercoagulability and immunomodulation contribute to increased maternal stroke risk. The postpartum state is associated with a substantially increased risk of thrombosis.

Here we are presenting a case of a 29-year-young postpartum female (post-LSCS day 12)with a known case of gestational diabetes and hypertension presented with a complaints of sudden onset of right sided weakness of both upper and lower limbs with decreased responsiveness. An imaging study showed left middle cerebral artery territory infarct.

Introduction

Maternal stroke, defined as an acute ischemic or hemorrhagic cerebrovascular event during pregnancy or the postpartum period, complicates approximately 30 per 100,000 pregnancies.

The rates of maternal stroke have been increasing in recent years. >90% of maternal mortality is seen in low-income countries.1Maternal stroke is a frequent cause of strokes among younger women (i.e., maternal stroke accounts for 18% of strokes in women 12–35 years of age in comparison with 1.4% of strokes in women 35–55 years of age)2. Strokes in older age groups are typically related to cardioembolic events, large artery atherosclerosis, or cerebral small vessel disease, whereas strokes in younger women may result from rarer mechanisms such as cervical artery dissection, venous infarction or hemorrhage attributable to cerebral venous thrombosis, primary hypercoagulable states, and reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome.

The risk of thromboembolic events in the 6 weeks postpartum has been estimated to be 15 to 35 times higher in the first week postpartum, in comparison with nonpregnant women, and the risk remains elevated up to 12 weeks postpartum.

There is a growing body of evidence that HDPs induce endothelial changes that have been linked to vascular pathology including cardiovascular, renal system and neurological system. Hemorrhagic strokes account for almost 60% of strokes in pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Case Presentation

A 28-year young postpartum female presented to the hospital with a history of sudden onset of right-sided limb weakness with deviation of mouth to left followed by decreased responsiveness. On arrival, her GCS was E4V1M5 with stable vitals and power in the right upper and lower limb was 0/5. She is a case of gestational diabetes mellitus and hypertension for the past 15 days.

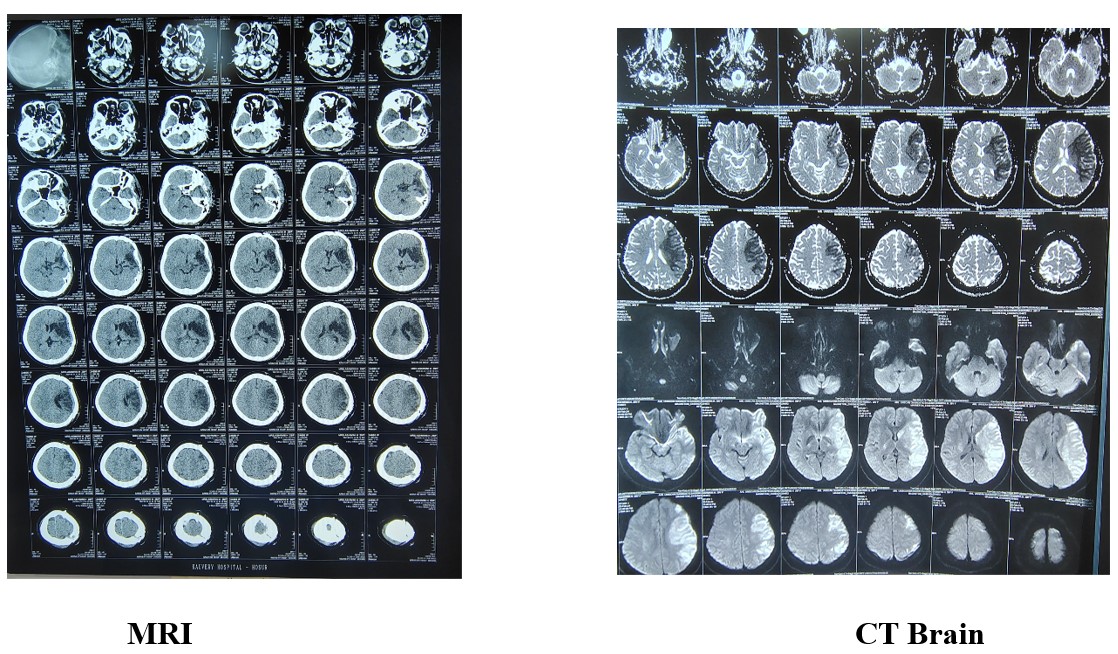

MRI Brain showed a large acute infarct at left MCA territory, signs of left ICA and MCA thrombosis. Thrombolysis has done with injection of Tenecteplase. The next day her GCS remained same with right side weakness of 0/5. Since CT BRAIN showed left MCA territory acute infarct with mass effect patient was taken up for decompressive craniectomy on 21/02/24.

Here are the MRI and CT BRAIN of this patient On POD 1 her GCS was E3VTM6, Pupils bilateral 3mm SRTL, started on anti-edema measures. Vitals stable. On POD 2, her general condition remained same and patient was extubated. Repeat CT BRAIN showed hypodense areas notes in left temporal, front parietal region, mass effect in left lateral ventricles.

Gradually her general condition improved, she was able to swallow and right side weakness improved from grade 0 to grade 3. She was discharged on postoperative day 11. As she was stable, she had cranioplasty (three months post craniotomy) on 21/05/24 and then discharged.

Discussion

Advancing maternal age at the time of birth and the increasing prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and other risk factors, such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, migraine, and infections, may contribute to increased rates of maternal stroke.

Risk factors for maternal stroke may be broadly classified as traditional cardiovascular or other risk factors. Traditional risk factors include older age, obesity, smoking, chronic hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and heart disease. Other risk factors include HDP, migraine, infections, and hypercoagulable states.

The risk of maternal stroke is higher in the peripartum and postpartum period (12 weeks after the delivery) than in the antepartum period. Hypertension remains the most prevalent modifiable risk factor for stroke among the general population and pregnant and postpartum women, as well. Preeclampsia and stroke are known to share common risk factors such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, heightened inflammatory responses, hypercoagulable states, and endothelial dysfunction. Infections are now recognized as a trigger for strokes in people of all ages,

Proposed pathophysiological pathways for the association between infections and maternal stroke include activation of the inflammatory cascade, causing a surge in inflammatory cytokines leading to platelet activation and aggregation; increased oxidative stress; and impaired endothelial function, all of which are linked with maternal stroke.

Factors associated with an increased risk of stroke during pregnancy and puerperium

| Ischemic stroke | Hemorrhagic stroke | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department | Physiological | Pathological | Physiological | Pathological |

| Cardiovascular | • Venous stasis/vasodilation • Venous congestion • Direct compression from the gravid uterus | • Chronic hypertension • Gestational hypertension • Preeclampsia/ eclampsia • Congenital heart disease • Rheumatic (valvular) heart disease • Peripartum cardiomyopathy • Patent foramen ovale. | • Hypervolemia • Increased cardiac output | • Chronic hypertension • Gestational hypertension • Preeclampsia/eclampsia |

| Hematologic | • Increase in factors VII, IX, X, XII, XIII; fibrinogen; von Willebrand factor • Reduced protein S activity • Acquired protein C resistance • Antifibrinolytics produced by placenta (PAI-1, PAI-2) | • 20210A mutation) • HELLP syndrome | ||

| Neurologic | • Migraine with aura • Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome | • Capillary proliferation • Arteriolar remodeling | • Brain arteriovenous malformations • Cerebral aneurysms • Moyamoya maculopathy • Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome • Migraine with aura |

|

| Obstetric | • Multifetal gestation • Multiparity • Endothelial damage due to delivery | • Cesarean section • Hyperemesis gravidarum • Amniotic fluid embolism • CVT due to low intracranial pressure from dural puncture | • Choriocarcinoma • Preeclampsia/eclampsia |

|

| Infectious/inflammatory | • Increased activation of the innate immune system • Shift from Th1 to Th2 • Heightened inflammatory response in third trimester | • Systemic lupus erythematosus • Connective tissue disorders • Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome • Puerperal infections • HIV infection Sepsis | • Sepsis | |

| Endocrine | • Increased estrogen • Increased progesterone | • Gestational diabetes • Diabetes mellitus • Obesity | ||

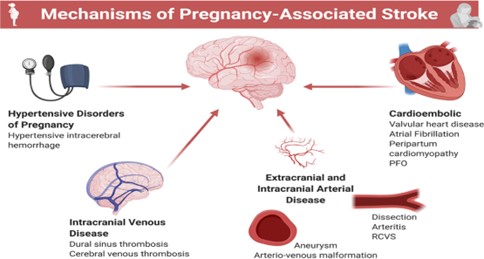

Pathophysiology

Multiple physiologic factors inherent to pregnancy likely contribute to the increased risk of stroke during pregnancy and puerperium. High levels of progesterone result in increased venous compliance and stasis, reaching a peak effect towards the end of pregnancy, coinciding with maximum direct compression of the fetus on the pelvic veins. Increased levels of estrogen result in higher production of procoagulant coagulation factors, including factors VII and X and prothrombin. Protein S levels decrease and there is an increase in activated protein C resistance in pregnancy. The placenta also produces plasminogen activator inhibitors, leading to a decrease in endogenous tissue plasminogen activator activity

Ischemia stroke

Arterial infarcts are more common during pregnancy and venous infarcts are more common during postpartum period. About 25% of infarcts are associated with pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Common arterial ischemic stroke mechanisms during pregnancy include cardioembolism, cervical artery dissection, and arterial vasospasm due to reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome can lead to severe disability or death if complicated by ischemic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage.50 % of cases have diverse etiology including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coagulopathy, APLA Syndrome, Lupus and sickle cell anemia. Pregnancy-specific etiology includes postpartum cardiomyopathy, postpartum cerebral angiopathy and choriocarcinoma. Amniotic Fluid embolism should be suspected in all stroke cases during labor or shortly after vaginal delivery.

Hemorrhagic stroke

It includes non traumatic ICH and SAH which have distinct causes.

Hemorrhagic infarction may also occur due to hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic strokes.

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia account for 40 to 50% of cases. 25 to 35% of cases are from vascular malformations such as brain arteriovenous malformation (AVM), cerebral aneurysm, cerebral cavernous malformation or fragile moyamoya collateral vessels. 30% of cases are idiopathic. The cerebral vasculature may be more susceptible to ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke during pregnancy and postpartum. Studies have shown pregnancy-related physiological changes, including arteriolar dilatation and remodeling, decreased cerebrovascular resistance, and increased blood-brain barrier permeability. Immunomodulatory and vascular changes in pregnancy may contribute to the mechanisms of both ischemic and hemorrhagic maternal strokes. Pregnancy is associated with changes in both innate immunity and T-cell-mediated immunity.

Independent of immunomodulatory mechanisms, the altered cerebral autoregulation associated with HDP may elevate cerebral wall tension in the fragile vessel walls and increase vulnerability to maternal stroke. Endothelial dysfunction, both systemic and cerebral, is a pivotal mechanism that results in the disruption of vascular tone, increased vessel reactivity, and, in some cases, vasogenic edema. In addition, preeclampsia has been linked with enhanced platelet aggregation

Most fatal maternal strokes could be prevented by earlier recognition of warning signs, such as severe hypertension and headache, and more aggressive blood pressure management

Women with preeclampsia, showed that prothrombotic states including systemic lupus erythematosus and sickle cell disease were associated with a higher risk of maternal stroke . Pregnancy with antiphospholipid syndrome increases the risk of recurrent ischemic stroke, preeclampsia, and preterm delivery

Cerebral venous thrombosis is another cause of maternal stroke, usually occurring in the postpartum period. During pregnancy and the postpartum period, hormonally mediated changes in the coagulation system shift the balance to a hypercoagulable state. Hypercoagulability, together with other mechanisms such as hypervolemic circulatory dynamics, venous stasis, and vascular endothelial injury in the setting of delivery increase the risk of thrombogenicity and may potentiate ischemic stroke risk,in particular, in the postpartum period. In addition, increased venous capacitance and venous pooling with resultant stasis, and reduced mobility, as well, may play a role in the increased risk of thrombotic events during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Imaging

As soon as acute focal neurologic deficits are identified in a pregnant or postpartum patient, stroke assessment should be performed rapidly by current guidelines.

Brain imaging is critical to decision making regarding acute stroke interventions. In most cases, CT is the fastest and most accessible imaging modality and thus is preferred when hyperacute treatment decisions are needed. The dose of ionizing radiation to the fetus from a non contrast head CT is 0.001 mGy to 0.01 mGy, far below the 50 mGy threshold above which adverse fetal effects become a concern. CT angiography should be obtained when large vessel occlusion or rupture of a vascular lesion is suspected, since these conditions are life threatening, similarly, mechanical thrombectomy should not be withheld because of fears of contrast toxicity to the fetus. If immediately available, MRI is reasonable but in most cases would result in unacceptable treatment delays

Management of Acute Stroke in pregnancy and postpartum

In general, pregnant women with acute stroke are best managed in tertiary stroke centers whenever feasible. A multidisciplinary team approach including obstetricians, obstetric anesthesiologists, and neurologists is recommended.

Symptoms include unilateral or weakness of the face, arm or legs, dysphasia, hemianopia and cerebellar features such as dysarthria and ataxia. Nonlocal symptoms such as generalized weakness or sensory disturbance, brief loss of unconsciousness, urinary or fecal incontinence, confusion and tinnitus. The FAST CAMPAIGN was created to promote public awareness of the symptoms and signs of stroke and to encourage rapid response.

- F – Face drooping

- A – Arm weakness

- S – Speech difficulty

T – Time to call Initial stroke management of pregnant women does not differ from that of the non-pregnant patient, with care focused on adequate oxygenation, maintaining circulatory integrity and euglycemia. In young patients presenting with ischemic stroke typically those of less than 45 years of age, antiphospholipid antibody testing is recommended as well as an echocardiogram to exclude a paradoxical embolism or other cardiac cause.

Current guidelines for acute ischemic stroke do not consider pregnancy to be a contraindication to IV thrombolysis if the deficits are disabling and the bleeding risks are acceptable. Among pregnant women with acute ischemic stroke and no other contraindications to systemic thrombolysis, systemic intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase is recommended if they present within 4–5 hr of symptom onset when the benefit outweighs the risk.6. Because alteplase is a large molecule, it does not cross the placental barrier.

Endovascular mechanical thrombectomy with stent retrievers has revolutionized the management of acute ischemic stroke among select patients with proximal large vessel intracranial arterial occlusions.

When a ruptured aneurysm is identified, interventional treatment should not be delayed because of pregnancy. Tranexamic acid may be safely used as an antifibrinolytic during pregnancy and postpartum.

First-line agents for blood pressure control in pregnancy are labetalol, methyldopa, and long-acting nifedipine. If necessary, nimodipine and nicardipine can also be used in pregnancy and during lactation. Lowering of blood pressure to below a threshold of 140/90 mm Hg is reasonable in pregnancy; fetal monitoring should be used to monitor for signs of placental hypoperfusion.

In addition to control of the bleeding source through neurosurgical or endovascular interventions,(emergent procedures such as aneurysm clipping/coiling, arteriovenous malformation embolization, and surgical resection) the treatment of hemorrhagic stroke typically includes blood pressure management, reversal of coagulopathy, and avoidance of complications such as vasospasm, intracranial hypertension, hydrocephalus, and seizures. Among patients with maternal stroke attributable to cerebral venous thrombosis, therapeutic anticoagulation with low molecular weight or unfractionated heparin remains the mainstay therapy.

The process of decision-making regarding the mode of delivery should be determined on an individualized basis. Maternal safety and outcomes should be prioritized.

Pregnancy presents unique recovery challenges after a stroke. Post-stroke recovery is often complicated by depression, which the pregnant or postpartum state may exacerbate and early involvement in psychiatry is recommended Primary Prevention of Maternal Stroke

Despite having higher overall mortality and higher cardiovascular morbidity, the majority of the maternal stroke survivors recovered well. Optimal management of the traditional risk factors plays a pivotal step in the prevention of maternal stroke.

Women with a history of chronic hypertension should be identified, monitored closely for superimposed preeclampsia, and treated to a targeted blood pressure goal

Concerning obesity, they will probably benefit most from lifestyle intervention strategies and counseling, including regular exercise, a healthy diet, achieving a desirable body weight, and discontinuing smoking before conceiving. An increase in physical activity during and before pregnancy not only reduces blood pressure but might also reduce the incidence of preeclampsia.

Prophylactic use of aspirin, before 16 weeks of gestation, in patients with 1 high or ≥2 moderate risk factors for preeclampsia has been found to reduce the risk of preeclampsia.

Secondary Prevention of Maternal Stroke

Women with a history of stroke are at risk for recurrent strokes. Women who develop maternal stroke secondary to cerebral venous thrombosis might benefit from low-molecular-weight heparin thromboprophylaxis during subsequent pregnancies.

For women with a history of ischemic stroke, contraceptive counseling is important. Systemic estrogen-containing contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy can increase the risk of thromboembolic events, and therefore alternative methods of contraception should be considered.

Lifestyle modification is a pivotal component of the secondary prevention strategy for all stroke subtypes, with emphasis on a healthy diet, regular exercise, weight loss, smoking cessation, and blood pressure control.

Conclusion

Maternal stroke is an important cause of maternal morbidity and mortality and is potentially preventable. The stroke recurrence during subsequent pregnancy was overall low, around 2%. However, many gaps remain in our understanding of the factors that may precipitate maternal stroke. Implementation of multidisciplinary health care team education and maternal stroke toolkits to improve recognition of cardiovascular complications and standardization of maternal health care delivery will help.

References

- IslamY.Elgendy, Syed BukhariAmr F.Barakat et al Maternal Stroke: A Call for Action CIRCULATION Volume143,Number7;16 February 2021 Pages: 727 – 738

- Miller EC, Gatollari HJ, Too G, Boehme AK, Leffert L, Elkind MS, Willey JZ. Risk of pregnancy-associated stroke across age groups in New York State. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:1461–1467. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3774

- Kamel H, Navi BB, Sriram N, Hovsepian DA, Devereux RB, Elkind MS. Risk of a thrombotic event after the 6-week postpartum period. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1307–1315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311485

- Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke2019;50(12):e344–e418. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000211

- Miller EC, Wen T, Elkind MSV, Friedman AM, Boehme AK. Infection during delivery hospitalization and risk of readmission for postpartum stroke. Stroke. 2019;50:2685–2691. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025970

- Ladhani NNN, Swartz RH, Foley N, et al. Canadian Stroke Best Practice Consensus Statement: acute stroke management during pregnancy. Int J Stroke2018;13(7):743–758. doi: 10.1177/1747493018786617

- Puac P, Rodriguez A, Vallejo C, et al. Safety of contrast material use during pregnancy and lactation. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am2017; 25(4):787–797. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2017.06.010

- Elgendy IY, Kumbhani DJ, Mahmoud A, Bhatt DL, Bavry AA. Mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2498–2505. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.070

- Amy Y.X. Yu, MD, MSc, Kara A. Nerenberg, MD, MSc, Christina Diong, MSc ;Maternal Health Outcomes After Pregnancy-Associated Stroke: A Population-Based Study With 19 Years of Follow-Up;Stroke ,AHA/ASAJOURNALS,Volume 54, Number 2 ; Published 23 January 2023

- LiisaVerho,MD MinnaTikkanen,PhD;Long-Term Mortality, Recovery, and Vocational Status After a Maternal Stroke;Register-Based Observational Case-Control Study;NEUROLOGY Volume 103 | Number 2 | July 23 2024.