Jenifer Theresal J

Senior Dietician, Kauvery Hospital, Tennur, Trichy, India

*Correspondence: +91 8148420506; dietary.ktn@kauvery.in

Abstract

In this article we shall discuss therapeutic nutrition among patients admitted to critical care units. The introduction states the importance nutritional therapies given during critical care. The nutritional assessment screening talks exclusively about Subjective Global Assessment (SGA). The protocol and the guidelines to follow SGA have been given. The normal recommendation of nutrients depends on the patient’s condition and composition of the body. There are six recommendations to be followed in nutritional therapy during critical care and they can achieve a 60% recovery rate in patients. Protein recommendations are very important when patient is fed through Ryles tube. Hygiene while handling Ryles tube feeding and its protocol have been discussed. Segregates has been given for parenteral nutrition in bar diagram. The importance of protein, fat, carbohydrates, electrolytes and micronutrients for parenteral nutrition has been discussed in bar diagram. There can be complications in following enteral and parenteral nutrition. By following the guidelines and protocols for therapeutic nutrition, the complications of enteral and parenteral nutrition can be reduced.

Background

Nutrition in the hospital setting has a significant role in recovery. It is very evident in the ICU. Critical illness is typically associated with a catabolic metabolic state in which patients are highly stresses and often demonstrate a systemic inflammatory response. This response is associated with complications of increased morbidity and mortality from infections, inflammation, multi-organ dysfunction, prolonged hospitalization, and high cost to the patient. Over the past three decades, the understanding of the molecular and biological effects of nutrients in maintaining homeostasis in the critically ill population has advanced substantially. Traditionally, nutrition support in the critically ill population was regarded as adjunctive care designed to provide exogenous fuels to support the patient during the stress response.

Nutrition therapy for critical care stay patients

The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) recently published evidence-based guidelines on medical nutrition therapy for critically ill patients. Early enteral nutrition (EEN) is recommended, as it is superior over delayed enteral nutrition (EN) and early parenteral nutrition (PN). When to start EEN in patients in shock is a matter of debate; however, EN can be commenced after the initial phase of hemodynamic stabilization, and it is not necessary to delay EN until vasopressors have been stopped.

Nutrition screening and assessment

Nutrition screening is done to identify patients at high nutritional risk. Nutrition assessment is a detailed evaluation of the nutritional status of the patient. Thus, a subset of patients at high nutrition risk is identified by nutrition screening, where their nutrition status is evaluated in detail through a nutrition assessment process. Eliciting a complete nutritional history is the first step in nutritional risk assessment. In critically ill patients, indirect information about patient’s nutrition can be taken from family members. Information such as unintentional weight loss during last 3-6 months and recent decrease in nutrient intake taken from family members can help to understand nutritional history of the patient. Among the assessment tools available, subjective global assessment (SGA) is inexpensive, quick and can be conducted at the bedside. It is a reliable tool for inferring outcomes in critically ill patients.

Practice guidelines

- Feeding should be tailored as per the patient’s requirement and level of tolerance.

- Protein requirement for most critically ill patients is in the range of 1.2-2.0 g/kg body weight/day.

- Calories should be in range of 25-30 Kcal/kg body weight/ day for most critically ill patients.

- In severely hypercatabolic patients such as extensive burns and polytrauma, ratio of Kcal: nitrogen should be 120:1 or even 100:1 has been accepted.

- For obese patients, adjustment in calorie and proteins must be done on basis of the body weight and BMI.

- Toronto formula is useful for estimating energy requirements in acute stages of burn injury and must be assessed and adjusted to changes in the parameters that are being monitored.

- Weight-based equations are preferred for energy-protein calculations.

| Nutrient | Recommendation |

| Energy | 11-14 kcal/kg actual body weight/day for patients with BMI in the range 30-50 kg/m2

22-25 kcal/kg ideal body weight/day for patients with BMI >50 kg/m2 |

| Protein | 2.0 g/kg ideal body weight/day for patients with BMI 30-40 kg/m2

2.5 g/kg ideal body weight/day for patients with BMI ≥40 kg/m2 |

Nutrition therapy and critical illness: practical guidance for the ICU, post-ICU, and long-term convalescence phases

| Recommendations | Rationale |

| Recommendation 1: Start early enteral nutrition in all critically ill patients within 48 h, preferably within 24 h when there is no reason to delay enteral nutrition (see the following recommendations). | Early enteral nutrition is associated with lower risk of infections and preserves the gut function, immunity, and absorptive capacity. |

| Recommendation 2: Delay early enteral nutrition in case of enteral obstruction. | Feeding proximal of an obstruction will lead to blow-out or perforation. |

| Recommendation 3: Delay early enteral nutrition in case of compromised splanchnic circulation such as uncontrolled shock, overt bowel ischemia, abdominal compartment syndrome, and during intra-abdominal hypertension when feeding increases abdominal pressures. | Absorption of nutrients demands energy and oxygen. In states of low flow or ischemia, forcing feeding into the ischemic gut may aggravate ischemia and lead to necrosis or perforation. |

| Recommendation 4: Delay early enteral nutrition in case of high-output fistula that cannot be bypassed. | Enteral feeding will be spilled into the peritoneal space or increase the fistula production. |

| Recommendation 5: Delay early enteral nutrition in case of active gastrointestinal bleeding. | Enteral feeding will limit the visualization of the upper gastrointestinal tract during endoscopy. |

| Recommendation 6: Delay early enteral nutrition in case of high gastrointestinal residual volume (> 500 mL per 6 h). | This threshold is associated with poor gastric emptying and may increase the risk of aspiration. Prokinetics and postpyloric feeding can circumvent this problem. |

Nutrition therapy for patients recovering from critical illness

During the recovery phase following liberation from mechanical ventilation, post-extubation dysphagia is common and occurs in 41% of critically ill adults, reported incidence ranges from 3% to 62% of patients. Due to prolonged ventilation, many of these patients suffer from severe dysphagia, leading to decreased energy, micronutrient, and protein intake, as well as increased rates of pneumonia, reintubation, and mortality. Oral intake can be further impaired by post-extubation ventilatory support with high flow nasal canula or other forms of non-invasive ventilation.

Importance of protein in diet of the critical care patient:

The catabolic response leads to reductions in muscle mass up to 1.3 to 1.5 kg/day during the first 10 days of ICU stay in patients with MODS (Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome).. Protein intake recommendations are dependent upon patient’s clinical status. Studies have shown beneficial effects on the loss of muscle mass and muscle protein synthesis from administration of higher dosages of protein

A balanced administration of macronutrients, including lipids, together with carbohydrates, is recommended. Special attention should be given to electrolyte status. Any significant decrease in potassium, phosphorus, or magnesium may endanger the patient and should be corrected promptly. Close monitoring of electrolyte status should continue throughout the ICU stay as clinically significant disturbances can occur, not only at admission in severe malnourished patients, but also during the course of the ICU stay, even in well-nourished patients.

Sarcopenic patients with a substantial decline in muscle mass have increased mortality risk, and high protein diet may improve their survival.

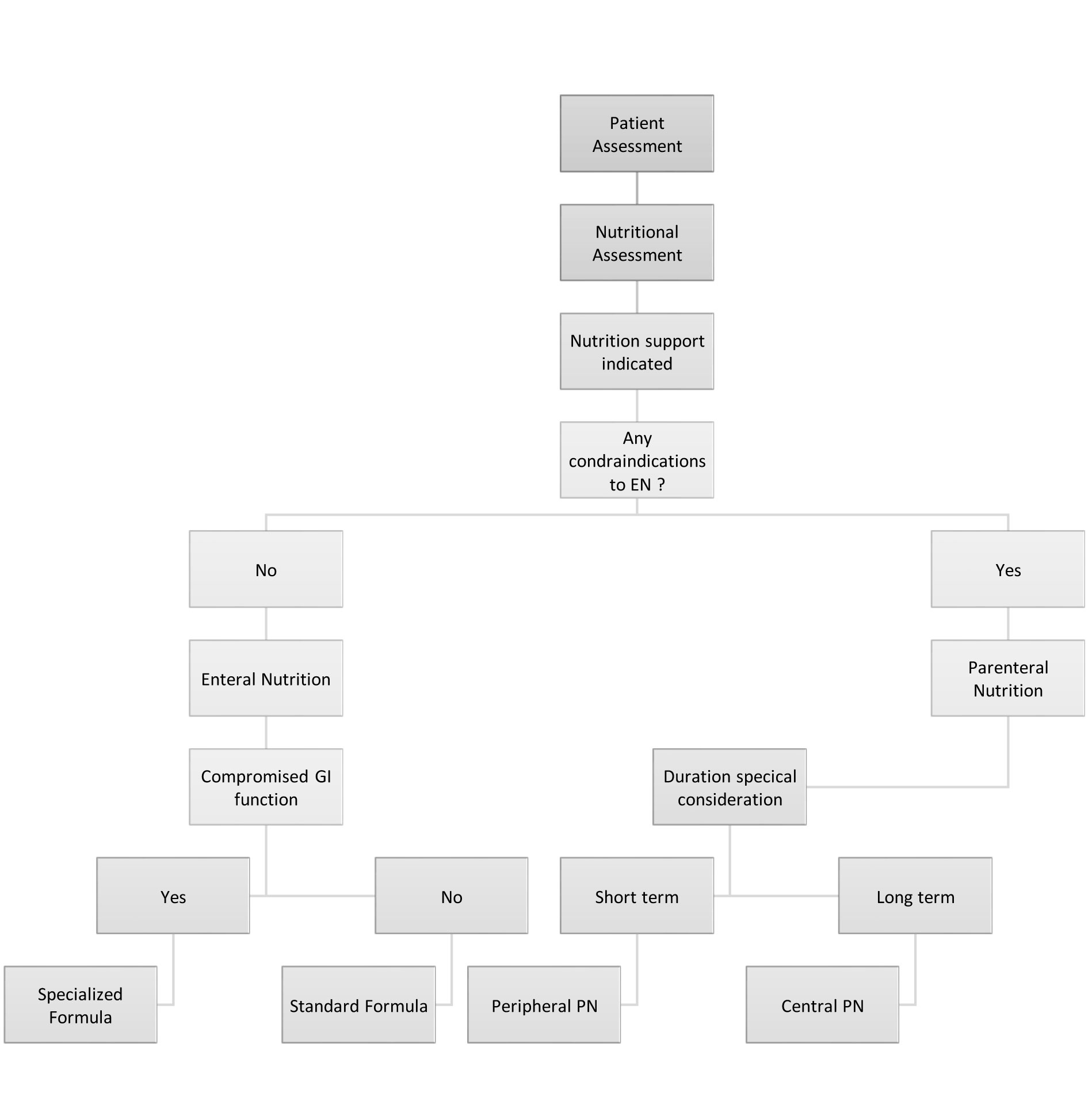

Contraindications to Enteral Nutrition Support

- Severe short-bowel syndrome (< 100-150 cm small bowel remaining in the absence of the colon or 50-75 cm remaining small bowel in the presence of the colon)

- Other severe malabsorptive conditions

- Severe GI bleed

- Distal high-output GI fistula

- Paralytic ileus

- Intractable vomiting and/or diarrhea that does not improve with medical management

- Inoperable mechanical obstruction

- When the GI tract cannot be assessed-for example, when upper GI obstructions prevent feeding tube placement.

EN is the preferred modality over PN as it has been shown to have cost, safety, and physiologic benefits. EN may reduce disease severity, complications, and length of stay, and improve patient outcome. Administration of PN typically requires insertion of a central venous catheter or peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC). Due to the risks of catheter-related complications and infection, current recommendations suggest that PN be considered after 7-10 days if early EN is not feasible to meet >60% of nutrition needs following ICU admission. In multicenter, randomized controlled trials, later PN was associated with lower ICU mortality, shorter ICU length of stay, fewer infections and other complications, and greater reduction of costs when compared with early initiation.

Ryle’s Tube feeding and nosocomial infections (healthcare-associated infections):

“Nutrient content” and “microbiological safety” are very important factors in patients on tube feeding. Long-term enteral tube feeding with elemental diets is one of the common but relatively unrecognized risk factors for the development of Clostridium Difficile colitis. Contamination and batch-to-batch inconsistency are more likely with homemade or blenderized feeds than with scientific feeds. Maintaining the microbial quality of hospital-prepared blenderized feeds within the published standards of safety is difficult.

Various factors responsible for bacterial contamination of handmade formulations include unhygienic original food items, food-making process and devices like blenders. Hygiene of the floor, air-conditioning, environment of kitchen, negligence by kitchen staff/nurses and food carriage process to the wards in hot and humid conditions are also equally important factors. These issues should be particularly evaluated in Indian settings. The closed system ready-to-use formulae are less prone to bacterial contamination since they do not require further preparation and hence can be used at patient’s bed side. Feeding-related nosocomial infections in the critically ill patients can be prevented by maintaining the sterility of formula feeds.

Practice guidelines

- Scientific formula feed should be preferred over blenderized feeds to minimize feed contamination.

- Whenever feasible, closed system ready-to-hang formula feeds should be preferred

- Blenderized formulae are more likely to have bacterial contamination than other hospital prepared diets

- Hygienic methods of feed preparation, storage, and handling of both formula feeds and blenderized feeds are necessary

Parenteral Nutrition

This route is usually employed in patients with gastrointestinal failure and when all attempts at initiation of enteral feeding fail. It is indicated in diffuse peritonitis, intestinal obstruction, intractable vomiting, paralytic ileus and severe diarrhea. This route of feeding may also be used in addition to the enteral route as several studies indicate that the enteral feeding is associated with considerable incidence of underfeeding. Underfeeding in patients who receive less than 25% of target feed has been shown to have higher risk of nosocomial pneumonia. It is suggested that all attempts should be made to start enteral nutrition initially and parenteral nutrition should be reserved for patients with absolute indications and in cases of failure of enteral nutrition.

Parenteral nutrition is usually given through central venous lines but can also be given through peripheral venous lines depending on the osmolality of the solution used. Thus, the complications are more frequent with parenteral route and are associated with catheter insertion and infection.

Central venous lines meant for parenteral nutrition should be inserted under strict aseptic conditions and a dedicated line should be used for this purpose and interruptions and reconnections should be limited and, if required, should be done with aseptic precautions.s

Parenteral nutrition is usually given as sterile emulsion of water, protein, lipid, carbohydrate, vitamins, minerals, and trace elements. It contains:

Proteins: It is present in the form of amino acids in a soluble form and should include essential amino acids i.e. those which cannot be synthesized inside the body. It should contain equal proportions of both essential and non-essential amino acids.

Fats: It is usually given in the form of “intralipid” which is an emulsion made from soya with chylomicron-sized particles. The lipids not only act as source of energy but also supplement essential fatty acids and also help in absorption of fat-soluble vitamins.

Carbohydrates: This is given in the form of glucose which is readily absorbed and is an important source of energy in various vital organs.

Electrolytes and Micronutrients: These may be included in the emulsion or may have to be provided separately. The requirements of these electrolytes and trace elements depend upon the disease and the condition of the patient

Complications of Enteral nutrition (EN)

As already discussed, aspiration is the most common complication leading to pneumonia which can be prevented by various measures including nursing education and good oral hygiene. Another important complication is diarrhea; however, it is not an indication to interrupt feeding and can be easily managed.

Complications of Parenteral nutrition (PN)

The most common complications are catheter related and include pneumothorax, hemothorax, arterial and nerve injury, and the infection. It has been suggested that more complications arise due to overfeeding and hyperglycemia rather than parenteral nutrition itself. Nevertheless, infection is a dreaded complication and all measures should be taken to prevent the infection.

Parenteral nutrition can also predispose to fatty liver, cholestasis, acalculous cholecystitis, and electrolyte imbalances and thus regular monitoring of various blood investigations is mandatory to prevent such complications especially in patients with long stay in intensive care.

Conclusion

Malnutrition is a common problem in critically ill patients and is associated with a poor outcome. Enteral nutrition should be started initially and as soon as possible in all the patients in which it is safe to do so. Parenteral nutrition should be reserved for the patients in whom enteral nutrition cannot be started but overfeeding should be avoided. Both types of nutrition are associated with complications which can be prevented by set protocols and by education of nursing personnel involved in the care of critically ill. In all these patients, it is vital to achieve strict glycemic control by using insulin.

References

- Mehta Y, et al. Practice guidelines for nutrition in critically ill patients: a relook for Indian scenario. Ind J Crit Care Med. 2018;22(4):263.

- McClave SA, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40:159-211.

- Jolliet P, et al. Enteral nutrition in intensive care patients: A practical approach. Working Group on Nutrition and Metabolism, ESICM. European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intens Care Med. 1998;24:848-59.

- Cook AM, et al. Nutrition considerations in traumatic brain injury. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008;23:608-20.

- Bajwa, SJS, et al. Critical nutritional aspects in intensive care patients. J Med Nutrit Nutraceut 2012;1(1):9.