Acute cerebral sinus venous thrombosis with different presentations and different outcomes: A case series

Dr. Gayathri Krishna Reddy, Dr. Alisha Margarette

Department of Anesthesiology, Kauvery Hospital, Hosur

Abstract

Cerebral sinus venous thrombosis (CSVT) is a relatively rare form of venous thromboembolism and accounts for 0.5 to 1% of all strokes. It is usually seen in young adults and children. Its clinical presentation is variable, making it difficult to diagnose; requires a high index of clinical suspicion in conjugation with neuroradiological diagnostic support. It is a condition that can be frequently overlooked due to the vague nature of its clinical and radiological presentation. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to prevent long-term disability and for better outcomes of the patient.

Background

Cerebral sinus venous thrombosis accounts for 0.5–1.0% of unselected stroke admissions and is about three times as common in women than in men, probably partly due to its association with pregnancy, the puerperium, and use of oestrogen-containing oral contraceptives.

It is a multi-factorial disease with variable presentation. The presentation depends on the site and extent of thrombosis, patients age and underlying etiological factors. Thrombosis in the cerebral veins or cerebral venous sinuses causes increased venular and capillary pressure and decreased CSF absorption respectively. This causes increase in intracranial pressure leading to cytotoxic and vasogenic edema causing disruption of blood brain barrier and haemorrhagic infarction.

Case Series

Case 1

A 30-year-old female, the homemaker by occupation, presented to the ER in a drowsy state following an episode of laughing (GELASTIC) seizures, associated with sudden loss of consciousness for a brief period, approximately about 5 min. She regained consciousness but was in a post ictal state with sweating and headache. No h/o vomiting. There was no history of previous such episodes, no significant family history, no h/o any comorbidities like diabetes, hypertension, thyroid disorders, etc.

On general examination, she was obese and had a male pattern of distribution of hair. Her vitals were deranged with high blood pressure recordings around 180/100 mmhg, but her GCS was 15/15. She was conscious and responded to commands at the presentation.

She was initially stabilized with anti-epileptic measures to prevent further seizure episodes and was simultaneously investigated for the cause.

CT-brain was ordered and it revealed hyperdense areas of the superior sagittal sinus. She was provisionally diagnosed with a case of acute cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. The patient was started on anti-platelet and anti-coagulant treatment. Hydration and anti-epileptic measures were continued.

On the second day of admission, her GCS was gradually dropping and the muscle power of the left upper and lower limbs decreased. Then she was further evaluated for etiology.

Lipid profile, anti-thrombin-III, protein-c, protein-s, anticardiolipin antibody, 2-D ECHO, and MRI brain with contrast and MR venogram were ordered, to rule out pro-thrombotic conditions and intracranial defects like tumors, AV -malformations, dural fistulas, hematological causes and any other systemic diseases.

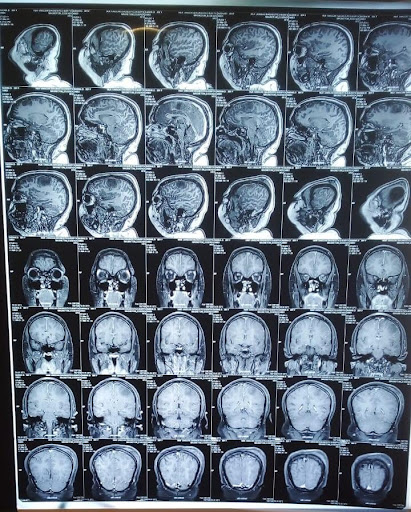

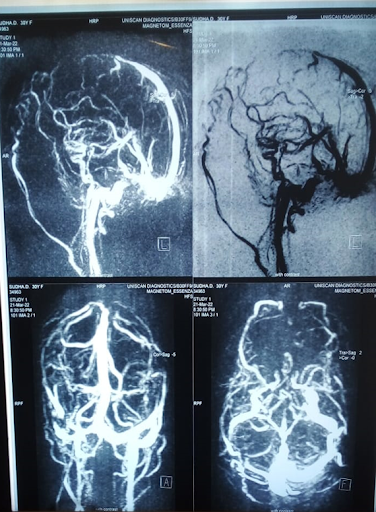

MRI-brain with contrast and MR venogram revealed complete thrombosis of anterior /mid one-third of the superior sagittal sinus and partial thrombus in the right transverse sinus. Multiple venous infarcts at both the frontal and partial lobe were seen, with regional mass effect.

Other blood investigations and 2d-echo were normal.

She was continued with anti-epileptic, anti-platelet and anti-coagulant treatment and anti-edema measures were added.

.

Her clinical condition improved, and on the fourth day of treatment, a repeat CT-brain was done to know the prognosis and the effectiveness of the given treatment. It revealed a hemorragic venous infarct with hypodense edema in the left high frontoparietal region and a mild mass effect on the left lateral ventricle with a mid-line shift to right about 3–4 mm.

As she was improving clinically and radiologically, she continued with the same treatment. After about a week of medical management, her clinical condition completely recovered and was discharged with anti-epileptic and anticoagulant medications. She was advised to follow up after 15 days.

Case 2

A 19-year-old male, with no known comorbidities, was brought to the ER with complaints of involuntary movements in both upper and lower limbs associated with up rolling of eyes and drooling of saliva and loss of consciousness. He had no similar complaints in the past.

He was hemodynamically stable at presentation, but was febrile and had poor mental status- GCS being E1, V1, M2. Pupils were equally reacting to light.

He was intubated; his airway was secured and relevant investigations were sent for.

CT-Brain plain showed features suggestive of acute dural sinus thrombosis involving anterior superior sagittal sinus.

CT-Brain Angiogram showed acute dural sinus thrombosis involving anterior superior sagittal sinus with acute venous hemorrhagic infarct.

On day 0, the patient slowly developed signs of increased intracranial pressure with bilaterally sluggishly reacting pupils.

Immediately repeat CT-brain was done, which showed multiple haemorrhagic areas with edema in bilateral frontal region with mass effect.

Anti-edema, anti-platelet and anti-epileptic measures were started and continued along with good hydration.

On day 2 he sustained a sudden cardiac arrest and ROSC was achieved and was started on inotropic supports.

Blood gas analysis showed severe metabolic acidosis and hypernatremia. And correction was given for the same along with anti-platelet, anti-edema and anti-epileptic measures. He had continuous temperature spikes for which antipyretics were administered to maintain normothermia.

On day 3, he again sustained a sudden cardiac arrest despite best resultative efforts the patient could not be revived. And was declared clinically dead, after confirming the clinical signs of death.

Discussion

Cerebral sinus venous thrombosis is a rare form of venous thrombosis and based on the time of onset of clinical symptoms, there are 3 subtypes.

- Acute: < 48 h

- Sub acute: > 48 h < 30 days (most common form)

- Chronic: > 1 month

Anatomy of the Cerebral Venous System

Cerebral venous system, divided into the superficial and deep venous system, is present in between endosteal and meningeal layers of duramater. The superficial system comprises of the dural sinuses and cortical veins; the two major superficial sinuses are the sagittal sinus and cavernous sinus. The superior sagittal sinus drains into transverse sinus which then drains into straight sinus. The cavernous sinus drains into transverse and sigmoid sinuses. The cortical veins are the veins of Labbe and sylvian and middle cerebral veins. The deep system consist of straight, lateral, and sigmoid sinus and deeper cortical veins. Both the superficial and deep venous systems eventually drain into the Internal Jugular Veins

Risk Factors

It is a multi-factorial disease with at least one risk factor present in most of the affected individuals. Likely, hereditary risk factors like coagulopathies, local infections like meningitis, local head and neck infections, intracranial tumours, head trauma, systemic vasculitis like SLE, jogrens, other factors like OCP usage, pregnancy, dehydration, history of recent travel, and recently proved COVID 19 are the major risk factors for CVT. Prothrombotic conditions are the most common implicated risk factor.

Thrombosis of cerebral veins and cerebral venous sinuses forms main pathophysiology responsible for all the clinical features of CSVT. Thrombosis leads to increased venular and capillary pressure which in turn increases in intracranial pressure leading to cytotoxic and vasogenic edema causing disruption of blood brain barrier and hemorrhagic infarction.

Decreased CSF absorption and drainage due to sinus occlusion can result from dysfunction of arachnoid granulations, which in turn can result in increased intracranial pressure. Raised ICP in turn reduces cerebral perfusion pressure followed by cytotoxic edema.

Clinical Features

Cerebral sinus venous thrombosis has a vague form of presentation. Most common presentation includes signs of raised intracranial pressure such as headache, decreased visual acuity, papilledema, focal neurological deficits, seizures, and diffuse encephalopathy, uncommon presentations include subarachnoid hemorrhage, thunderclap headache, recurrent transient ischemic attacks, tinnitus, isolated headache, and multiple cranial nerve palsies. Headache is an extremely common symptom and many will have isolated headache or new atypical headache that progresses steadily over days to weeks despite treatment may suggest the diagnosis.

Diagnosis

A panel of the test are done to rule out most of the risk factors starting from complete blood picture, coagulation profile, factor-v mutation, protein-c, protein-s deficiencies, anti-phospholipid antibodies, prothrombin gene mutations, lumbar puncture and diagnostic imaging like CT-brain, MRI to make the definitive diagnosis and to rule out various etiological factors. The main goal in doing diagnostic imaging of CVT both (invasive and noninvasive) is to determine vascular and parenchymal changes present.

Noninvasive modalities CT, MRI, Ultrasound

CT – initial neuroimaging test in patients with new onset neurological symptoms. The primary finding in acute CVT on non-contrast CT is hyper density of a cortical or dural sinus. Thrombosis of superior sagittal sinus, posterior portion, appears as a dense triangle or filled delta sign

Contrast-enhanced CT may show enhancement of the dural lining with a filling defect.

MRI-Brain with contrast and MR Venogram are the diagnostic tests of choice to make the definitive and early diagnosis of CSVT.

In MRI-Findings are variable, and may include ‘’hyperintense vein signâ€

Invasive modalities

Cerebral Angiography and Direct Cerebral Venography – these techniques are reserved for situations in which the MRV or CTV are inconclusive or endovascular procedure is planned.

An early follow-up CTV OR MRV is recommended in CVT patients with persistent or evolving symptoms despite medical treatment

Treatment

Treatment includes primarily thrombolysis, anti-epileptics, anti-coagulants, anti-edema measures. The cause should be identified and treated along with the primary symptomatic treatment.

Initial Anticoagulation (Unfractioned Heparin, LMWH): prevents thrombus growth, facilitate recanalization and prevents DVT or PE.

Fibrinolytic therapy: Thrombolytic therapy is used if clinical deterioration continues in spite of anticoagulant or if the patient has elevated intracranial pressure that evolves despite treatment.

Antiepileptics: Since seizures increase the risk of anoxic damage anticonvulsant treatment should be started even with a single episode of seizure (Class-1 Level of evidence -B). In the absence of seizure prophylactic use of antiepileptic drugs is not recommended (Class-3; Level of evidence-B).

Aspirin:

No controlled trials or observational studies that directly assess the role of aspirin in the management of CVT

Steroids:

May have a role in CVT by decreasing vasogenic edema, but may enhance hypercoagulability (Class-3; Level of evidence- C).

Anti-edema measures

The superior sagittal sinus is the principal site for CSF absorption through the arachnoid granulation the function of these granulations is impaired resulting in failure of absorption of CSF causing raise in ICP which in turn causes vasogenic edema which needs to be controlled using anti edema measures.

Obstructive hydrocephalus if present, ventriculostomy is indicated.

Antibiotics

Local and systemic infections can be complicated by CVT, the management of patients with a suspected infection and CVT should include administration of appropriate antibiotics and surgical drainage of infectious source (Class-1; Level of evidence-C).

Decompressive craniectomy surgical decompression within 48 h of stroke onset improves functional outcome in patients with neurological deterioration due to severe mass effect or intracranial haemorrhage causing intractable intracranial hypertension (Class- 2b; Level of evidence -C).

Recent advances

Many Endovascular interventions have been reported to treat CVT. These include direct catheter chemical thrombolysis and direct mechanical thrombectomy with or without thrombolysis (Class-2b; Level of evidence-C).

Catheter thrombectomy for patients with extensive thrombus that persists despite local administration of fibrinolytic agent.

The penumbra system is a new-generation neuroembolectomy device for re-canalization is under study which yielded very good results in re-canalization of the occluded vessels, the others being Merci and AngioJet systems.

Long-term management and Recurrence of CVT

Each individual patient should undergo risk assessment and the patients risk level and, risk of bleeding, risk of thrombosis without anti-coagulation should be considered to continue anticoagulation therapy.

The overall risk of recurrence of any thrombotic event after a CVT is nearly 6.5%, ranging from 3.4% to 4.3%. Patients with severe thrombophilia have increased risk of CVT.

Conclusion

Cerebral sinus venous thrombosis is a rare form of cerebrovascular disease, when diagnosed and treated at an early stage appropriately along with neuroradiological support, a good prognosis and clinical outcome can be attained.

References:-

[1]Saposnik G, et al. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: A statement for health care professionals from American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke 2011;42(4):1158-92.

[2]Liao W, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: Successful treatment of two patients using the penumbra system and Review of Endovascular approaches. Neuroradiol J. 2015;28(2):177–83.

[3]Ulivi L, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis: A guide. Pract Neurol. 2020;20(5):356–67.

[4]Alvis- Miranda HR, et al. Cerebral sinus venous thrombosis. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2013;4(4):427–38.

Dr. Gayathri Krishna Reddy

Senior Consultant, Anaesthesia