Journal Scan

A review of 20 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

From the desk of the Editor-in-Chief

(1). Xu M, et al. Eruptive Xanthoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:e58.

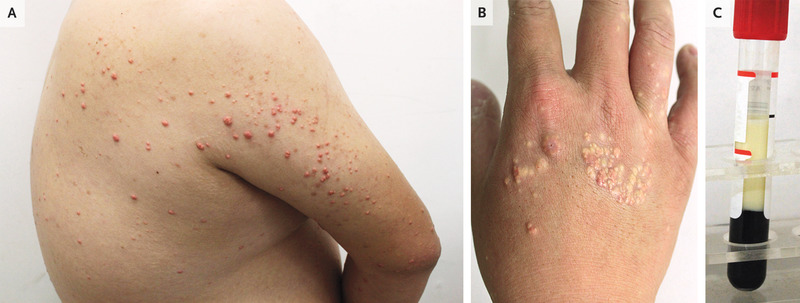

A 27-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on his back, arms, and hands that had developed 1 week earlier. He had a history of obesity and consumed a high-fat diet with frequent alcohol use. He had no known family history of dyslipidemia, vascular disease, or pancreatitis. On physical examination, scattered pink-yellow papules were present on the upper back, extensor surfaces of the upper arms (Panel A), and dorsa of the hands (Panel B). A fasting blood sample was grossly lipemic (Panel C). The triglyceride level was 10,650 mg per deciliter (120.2 mmol per liter; reference value, <151 mg per deciliter [<1.7 mmol per liter]), and the total cholesterol level was 1102 mg per deciliter (28.5 mmol per liter; reference value, <201 mg per deciliter [<5.2 mmol per liter]). A diagnosis of eruptive xanthomas due to severe hypertriglyceridemia was made. The differential diagnosis includes molluscum contagiosum, sebaceous hyperplasia, and generalized eruptive histiocytoma, but eruptive xanthomas should be suspected in patients with risk factors. The patient was referred to the internal medicine clinic for further evaluation and treatment. After 1 month of treatment with fenofibrate, along with alcohol cessation, exercise, and a low-fat diet, the skin lesions abated.

(2). Grover N. Pathogens Jumping to Humans From Animals Becoming More Frequent, Warns WHO. 2022.

LONDON: Outbreaks of endemic diseases such as monkeypox and lassa fever are becoming more persistent and frequent, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) emergencies director, Mike Ryan, warned on Wednesday.

As climate change contributes to rapidly changing weather conditions like drought, animals and human are changing their behavior, including food-seeking habits. As a result of this “ecologic fragility”, pathogens that typically circulate in animals are increasingly jumping into humans, he said.

“Unfortunately, that ability to amplify that disease and move it on within our communities is increasing – so both disease emergence and disease amplification factors have increased.”

For instance, there is an upward trend in cases of Lassa fever, an acute viral illness spread by rodents endemic to Africa, he said.

“We used to have three to five years between Ebola outbreaks at least, now it’s lucky if we have three to five months,” he added.

“So there’s definitely ecological pressure in the system.”

Ryan’s commentary comes as cases of monkeypox continue to rise outside Africa, where the pathogen is endemic.

On Wednesday, the WHO said it had so far received reports of more than 550 confirmed cases of the viral disease from 30 countries outside of Africa since the first report in early May.

Meanwhile, although COVID-19 cases are declining globally, there are regions such as the Americas with concerning trends, WHO director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus highlighted in a briefing on Wednesday.

In North Korea, officials suspect there are over 3.7 million cases of fevered people, that could be COVID, as the country battles against its first ever COVID outbreak. It declared a state of emergency and imposed a nationwide lockdown last month.

Ryan said although the WHO had offered the country support in terms of vaccines, treatments and other medical supplies, it had encountered problems in securing access to raw data that would reflect the situation on the ground.

The experience of COVID has triggered the WHO to kickstart a process to draft and negotiate an international treaty to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

Pandemics, like climate change, affect every citizen on the planet, said Ryan.

“We’ve seen the difficulties we faced in this pandemic – we may face a more severe pandemic in the future and we need to be a hell of a lot better prepared than we are now,” said Ryan.

“We need to establish the playbook for how we’re going to prepare and how we’re going to respond together. That is not about sovereignty. That’s about responsibility.”

(3). Walker S. Patient advocacy: an antidote to loneliness and more. 2022

I wish it was altruism-or something equally as laudable-that led me to patient advocacy. But if I am being honest, it was a much more pedestrian reason: loneliness.

The advent of social media was still a long way off in 1986 when I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at the age of 6 years. And I hardly knew anyone else with the condition. Type 1 diabetes is relentless with gruelling and constant self-management requirements. Although it was a huge part of my daily life, I did not feel that it was a part of me that I could share. I did not believe that people outside of my immediate family would understand and I did not want to feel any different from others than I already did. Like many children, I was under the impression that not talking about uncomfortable things would minimise them. Years later, I learnt that what I went through in those early days was similar to what many people experience after the diagnosis of a chronic, long term condition regardless of its nature.

I quietly managed the condition through adolescence but then, on a whim, in my early 20s, I signed up for the American Diabetes Association’s Call to Congress. The Call to Congress brings together people affected by diabetes in the United States every year to meet with policy makers in order to advocate for increased funding and research into all types of diabetes. Again, my motivation was less than honourable-I was living in Boston (MA, USA) and I was mainly attracted by the free trip to Washington, DC (USA).

But what started as a free trip quickly morphed into something more. Surrounded by people with similar experiences to mine made me feel like part of a community. What usually made me feel alone, instantly connected me with others; my condition meant entry into a vibrant and meaningful community. I had finally found a consolation to living with a chronic condition. Talking with policy makers, I recognised my personal story helped to bring data and statistics to life and that my lived experience could help them to see things through a different lens. I also saw how parts of my experience as someone living with diabetes specifically, and as a patient more generally, were universal and that patients had a tremendous amount to bring to the table.

Shortly after, I moved to the UK to do a master’s degree in Health, Community, and Development at the London School of Economics. The masters provided me with a clear understanding of the main tenets of global healthcare systems and public policy. After graduating, I embarked on a career in pharmaceutical market access and strategy consulting.

Meanwhile in my spare time, I pursued advocacy work for type 1 diabetes, such as lobbying members of parliament for increased access to treatment, participating in decisions for funding research, and attending conferences as a patient representative. Through my dual professional and personal experience, I saw that the conversations and debates that I was privy to as a patient advocate did not always play out meaningfully at the policy level. Frustratingly, I saw that the treatment and management that patients valued was rarely prioritised.

When asked to advise on the launch and running of BMJ Medicine, I was thrilled, but also slightly apprehensive. Would I be able to represent the patient community writ large? But then I thought back to the lessons that I started learning on that trip to Washington, DC so many years ago. The desire to be heard, to be involved in decisions that affect us-in other words, to have a seat at the table-is universal, and timeless.

I do not know what it is like to live with another condition but I do understand that, regardless of the condition, patient contributions are essential. These contributions-whether at the individual level, such as reviewing a research study, or at a broader level by speaking for a community as a whole, or anywhere in between, can and do guide healthcare improvements. Bringing this lived experience to bear in healthcare research, policy, and practice is essential to increasing the quality, safety, value, and sustainability of health systems. I will advocate for that through my role at BMJ Medicine. As I also understand that a diversity of voices and experiences is required to prevent bias and tunnel visions in healthcare decisions making, I will work to ensure the inclusion of those traditionally marginalised or hardly reached.

BMJ Medicine’s commitment to partnering with patients and the public is more than making patients feel heard. It is a recognition that this involvement is the only way to ensure that medical journals are relevant, practical, and clinically impactful. Representing the patient community in my role as patient adviser to BMJ Medicine is the perfect antidote for loneliness and a valuable opportunity to help improve care. I hope that my experience will encourage fellow patients who are still hesitant to get involved in advocacy work to take the plunge.

(4). Xiao-Yan Y, et al. Electrocardiogram Findings Worthy of Vigilance: A Rare and Fatal Disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2022.

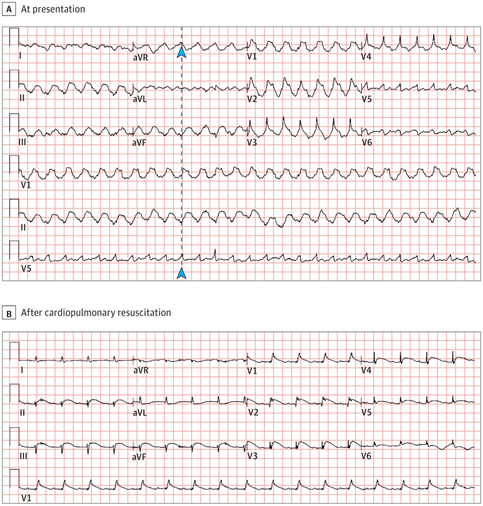

A patient in the 20s without a noteworthy medical history presented to the emergency department with chest pain and dyspnea. The patient began experiencing palpitations and symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection 3 days prior. Vital signs revealed a temperature of 36.5 °C, heart rate of 88 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 22 breaths per minute, blood pressure of 105/70 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation of 89% on room air. The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) is shown in Figure, A. The patient lost consciousness 20 minutes after arriving to the emergency department, and blood pressure decreased to 67/43 mm Hg. The ECG obtained after cardiopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillation is shown in Figure, B. Testing results revealed elevated levels of troponin T (4.74 μg/L; normal range, 0-0.03 μg/L) and pro-brain natriuretic peptide (4850 pg/mL; normal range, <300 pg/mL; to convert to ng/L, multiple by 1.0). C-reactive protein was elevated to 18.50 mg/L (normal range, 0-6 mg/dL; to convert to mg/L, multiply by 10), and procalcitonin was elevated to 39.68 ng/mL (normal range, 0-0.05 ng/mL). Findings from transthoracic echocardiography revealed severe left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction, 38%) and wall motion abnormalities in multiple vascular territories.

Electrocardiographic Findings

(A). In the initial electrocardiogram, through the R wave of lead V5 along the dotted line, it can be determined that the QRS complex of lead aVR is upward (arrowheads) and pure R wave in leads V1 and V2, which supported the diagnosis of ventricular tachycardia.

(B). The electrocardiogram obtained after cardiopulmonary resuscitation demonstrated sinus tachycardia (105 beats/min); low QRS voltage in limb leads; ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, aVF, and V1 through V6; and ST-segment depression in leads aVR and aVL.

Questions: What is the most likely diagnosis? What will you do next?

Interpretation

Initial ECG (Figure, A) demonstrated an upward QRS complex in lead aVR and pure R wave in leads V1 and V2, which supported the diagnosis of ventricular tachycardia. Repeat ECG (Figure, B) showed sinus tachycardia; low QRS voltage in limb leads; ST-segment elevation (STE) in leads II, III, aVF, and V1 through V6; and ST-segment depression (STD) in leads aVR and aVL.

Clinical Course and Discussion

The provisional diagnosis was acute myocardial infarction (MI). However, coronary angiography revealed normal coronary arteries. Ejection fraction dropped to 19% on day 2, and an intraaortic balloon pump was inserted and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was initiated to support left ventricular function owing to hemodynamic instability. On day 3, troponin T reached maximum (80 μg/L). The patient was then diagnosed with fulminant myocarditis (FM). On day 7, an ECG showed complete atrioventricular block, and a temporary pacemaker was implanted. Despite receiving maximum supportive therapy, the patient died on day 9 of admission.

Fulminant myocarditis is the most severe type of myocarditis and is predominantly caused by viral infections. It is characterized by sudden and severe inflammation of the myocardium, resulting in cardiogenic shock, ventricular tachyarrhythmias or bradyarrhythmias, and multiorgan failure, and it can be fatal. Patients with FM can present with ECG changes, wall motion abnormalities, and disturbance in laboratory values. Therefore, distinguishing between MI and FM is important. In this case, MI was successfully differentiated from FM using coronary angiography. Patients with FM may present with the following main ECG findings.

ST-T changes in FM mainly include STD and T-wave flattening or inversion. The ECG results of a few patients can also show STE, which is usually transient. If Q wave appears, it will gradually disappear with the remission of the disease. Patients with FM mimicking ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction are usually young and have a history of recent infection and elevated inflammatory biomarkers. ST-segment elevation may be associated with extensive epicardial-myocardial ischemia caused by inflammation. Two STE patterns have been described: pericarditis and typical MI-like patterns.

The pericarditis pattern is more common and is characterized by J-point elevation and an upward concave shape of the ST segment, with or without terminal QRS notching or slurring. Diffuse elevations usually involving multiple leads (I, II, III, aVF, aVL, and V2 through V6) are present; however, aVR and V1 often have reciprocal STD. These STEs may be confused with the benign diffuse STEs present in the early repolarization pattern. A comparison with a previous ECG may be useful for establishing the differential diagnosis. A typical MI-like pattern is characterized by J-point elevation and an upsloping flat or convex ST segments in at least 2 contiguous leads, generally without reciprocal STD.

Fulminant myocarditis can induce both bradyarrhythmias and tachyarrhythmias. In addition, intraventricular conduction delays and bundle branch blocks also occur commonly in FM. Most of these arrhythmias resolve following hemodynamic recovery in FM. Transient inflammatory cell infiltration of the myocardium and edema of the myocardial cells and intermyocardial cellular spaces can cause transient conduction blocks in the myocardial conduction system.

Bradyarrhythmias include sinus arrest and sinoatrial and atrioventricular blocks. Patients may develop first- or second-degree, advanced, or complete atrioventricular blocks. The reported prevalence of complete atrioventricular block is 23% to 30%. High-degree atrioventricular blocks have been associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates in patients with myocarditis.

The most common tachyarrhythmia is sinus tachycardia, which mainly reflects the degree of systemic inflammation and/or hemodynamic impairment. Occurrences of atrial fibrillation and flutter have also been described in acute myocarditis. Ventricular arrhythmias (ventricular premature beats, ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation) occur frequently in FM and are an important cause of sudden cardiac death.

A low QRS voltage is defined as a QRS amplitude of 0.5 mV or less in all limb leads or 1 mV or less in all precordial leads. In a study by Nakashima et al, 18% of patients with acute myocarditis had a considerable decrease in QRS amplitude in limb and chest leads during the acute phase of illness. Proposed mechanisms explaining the low QRS voltages in FM include ventricular wall, pulmonary, and peripheral edema.

Fulminant myocarditis also results in inhomogeneous repolarization manifesting as QT-interval prolongation, which may predispose to arrhythmias. Although these ECG changes are not specific to FM, we would like to emphasize that FM should be suspected once the previously mentioned ECG changes are found in a patient with a history of recent infection, and clinicians should act vigilantly to diagnose and manage this potentially fatal condition.

Take-home Points

Fulminant myocarditis can result in cardiogenic shock, ventricular tachyarrhythmias or bradyarrhythmias, and multiorgan failure, and it can be fatal.

Electrocardiographic findings in patients with FM are often variable and can mimic MI.

ST-segment elevation is usually transient and can be divided into 2 patterns: pericarditis and typical MI-like patterns.

Ventricular arrhythmias in patients with FM are a major cause of sudden cardiac death.

(5). Cercek A, et al. PD-1 Blockade in Mismatch Repair-Deficient, Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. 2022.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation followed by surgical resection of the rectum is a standard treatment for locally advanced rectal cancer. A subset of rectal cancer is caused by a deficiency in mismatch repair. Because mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer is responsive to programmed death (PD-1) blockade in the context of metastatic disease, it was hypothesized that checkpoint blockade could be effective in patients with mismatch repair-deficient, locally advanced rectal cancer.

Methods

We initiated a prospective phase 2 study in which single-agent dostarlimab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody, was administered every 3 weeks for 6 months in patients with mismatch repair-deficient stage II or III rectal adenocarcinoma. This treatment was to be followed by standard chemoradiotherapy and surgery. Patients who had a clinical complete response after completion of dostarlimab therapy would proceed without chemoradiotherapy and surgery. The primary end points are sustained clinical complete response 12 months after completion of dostarlimab therapy or pathological complete response after completion of dostarlimab therapy with or without chemoradiotherapy and overall response to neoadjuvant dostarlimab therapy with or without chemoradiotherapy.

Results

A total of 12 patients have completed treatment with dostarlimab and have undergone at least 6 months of follow-up. All 12 patients (100%; 95% confidence interval, 74 to 100) had a clinical complete response, with no evidence of tumor on magnetic resonance imaging, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron-emission tomography, endoscopic evaluation, digital rectal examination, or biopsy. At the time of this report, no patients had received chemoradiotherapy or undergone surgery, and no cases of progression or recurrence had been reported during follow-up (range, 6 to 25 months). No adverse events of grade 3 or higher have been reported.

Conclusions

Mismatch repair-deficient, locally advanced rectal cancer was highly sensitive to single-agent PD-1 blockade. Longer follow-up is needed to assess the duration of response.

(6). Arslanian SA, et al. Once-Weekly Dulaglutide for the Treatment of Youths with Type 2 Diabetes. 2022.

Background

The incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus is increasing among youths. Once-weekly treatment with dulaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, may have efficacy with regard to glycemic control in youths with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, 26-week trial, we randomly assigned participants (10 to <18 years of age; body-mass index [BMI], >85th percentile) being treated with lifestyle modifications alone or with metformin, with or without basal insulin, in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive once-weekly subcutaneous injections of placebo, dulaglutide at a dose of 0.75 mg, or dulaglutide at a dose of 1.5 mg. Participants were then included in a 26-week open-label extension study in which those who had received placebo began receiving dulaglutide at a weekly dose of 0.75 mg. The primary end point was the change from baseline in the glycated hemoglobin level at 26 weeks. Secondary end points included a glycated hemoglobin level of less than 7.0% and changes from baseline in the fasting glucose concentration and BMI. Safety was also assessed.

Results

A total of 154 participants underwent randomization. At 26 weeks, the mean glycated hemoglobin level had increased in the placebo group (0.6 percentage points) and had decreased in the dulaglutide groups (-0.6 percentage points in the 0.75-mg group and -0.9 percentage points in the 1.5-mg group, P<0.001 for both comparisons vs. placebo). At 26 weeks, a higher percentage of participants in the pooled dulaglutide groups than in the placebo group had a glycated hemoglobin level of less than 7.0% (51% vs. 14%, P<0.001). The fasting glucose concentration increased in the placebo group (17.1 mg per deciliter) and decreased in the pooled dulaglutide groups (-18.9 mg per deciliter, P<0.001), and there were no between-group differences in the change in BMI. The incidence of gastrointestinal adverse events was higher with dulaglutide therapy than with placebo. The safety profile of dulaglutide was consistent with that reported in adults.

Conclusions

Treatment with dulaglutide at a once-weekly dose of 0.75 mg or 1.5 mg was superior to placebo in improving glycemic control through 26 weeks among youths with type 2 diabetes who were being treated with or without metformin or basal insulin, without an effect on BMI.

(7). Ting-Han T. Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:e62.

A 4-year-old boy had a 2-day history of right hip pain and limping. A radiograph showed a focal area of collapse in the right femoral head.

(8). Richeldi L, et al. Trial of a Preferential Phosphodiesterase 4B Inhibitor for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis for the 1305-0013 Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:2178-87.

Background

Phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibition is associated with anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects that may be beneficial in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Methods

In this phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, we investigated the efficacy and safety of BI 1015550, an oral preferential inhibitor of the PDE4B subtype, in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive BI 1015550 at a dose of 18 mg twice daily or placebo. The primary end point was the change from baseline in the forced vital capacity (FVC) at 12 weeks, which we analyzed with a Bayesian approach separately according to background nonuse or use of an antifibrotic agent.

Results

A total of 147 patients were randomly assigned to receive BI 1015550 or placebo. Among patients without background antifibrotic use, the median change in the FVC was 5.7 ml (95% credible interval, -39.1 to 50.5) in the BI 1015550 group and -81.7 ml (95% credible interval, -133.5 to -44.8) in the placebo group (median difference, 88.4 ml; 95% credible interval, 29.5 to 154.2; probability that BI 1015550 was superior to placebo, 0.998). Among patients with background antifibrotic use, the median change in the FVC was 2.7 ml (95% credible interval, -32.8 to 38.2) in the BI 1015550 group and -59.2 ml (95% credible interval, -111.8 to -17.9) in the placebo group (median difference, 62.4 ml; 95% credible interval, 6.3 to 125.5; probability that BI 1015550 was superior to placebo, 0.986). A mixed model with repeated measures analysis provided results that were consistent with those of the Bayesian analysis. The most frequent adverse event was diarrhea. A total of 13 patients discontinued BI 1015550 treatment owing to adverse events. The percentages of patients with serious adverse events or severe adverse events were similar in the two trial groups.

Conclusions

In this placebo-controlled trial, treatment with BI 1015550, either alone or with background use of an antifibrotic agent, prevented a decrease in lung function in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

(9). Papautsky EL. A full time job: a year with early-stage breast cancer. BMJ 2022;377.

Nobody told me that breast cancer is a full time job.

In my case-stage 2 invasive ductal carcinoma, a type responsible for 80% of cases-it turned out to be a job that doesn’t care that you have other responsibilities-two small children, a spouse, a career. Because I am a social scientist, it was a comfort to document my illness in a format that is familiar. So, I set out to make a real time self-study of my breast cancer journey, constructing a spreadsheet to track dates, descriptions, locations, and clinical roles associated with each of my clinical encounters, annotated with summaries and colour coded for purpose: diagnosis, chemotherapy preparation, chemotherapy, hospital admission, surgery, radiation, and so on it went. This is my journey-others may look different, and despite being an active participant in my care, I’ve used the passive voice here, to try to convey a lack of control that I felt, of being taken on a ride that I did not sign up for. Over a 13-month period, I experienced 16 rounds of chemotherapy, 34 rounds of radiation, and three surgeries, including a mastectomy and a salpingo-oophorectomy. I received care from two medical oncologists, a radiation oncologist, a breast surgeon, a plastic surgeon, a gynaecological oncologist, a radiation oncologist, and numerous nurses and physician’s assistants, not to mention the second and third opinions I sought from all cancer specialties. I was cared for at four separate locations. There were routine appointments, blood tests, diagnostic scans, a hospital admission for a neutropenic fever and consultations from genetic counselling, ophthalmology, cardiology, dermatology, psychiatry, nutrition, podiatry, and physical therapy.

“Most people work through chemo’ was the message. Yes, they do. But as well as the professional kind of work, cancer requires you to take on a second “job.” Between September 2018 and August 2019, 54% of my business days had at least one medical appointment, with only three weeks being appointment-free. For a patient, these multiple direct touchpoints with the healthcare system form a delicate dance of prioritizing topics, symptoms, and concerns over a limited snapshot of a face-to-face encounter with one’s clinician.

On top of these direct touchpoints, there was everything that happened in between-the indirect ‘care-between-the-care,” as Patricia Flatley Brennan and Gail Casper describe it. Each day (medical appointment or not) had an effort and time cost associated with it-productivity loss due to fatigue, requiring additional sleep and reduced activity levels; management of side effects such as brain fog, gastrointestinal and dermatological issues; emotional distress (both my own and that of loved ones); logistics; countless trips to the pharmacy, purchasing of self-care supplies. I shan’t go on. And now that active treatment is over, I live with an ever-present (and often overwhelming) fear of recurrence. The perspective of those who straddle both worlds, the bilingual patient-researchers, is of tremendous value.

During my journey, I came upon the work of Trish Greenhalgh, whose autoethnography on adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer changed the way that I think about wearing multiple hats of a researcher and a patient, and Rosamund Snow-both of whom pioneered efforts to move the needle forward in the need to consider the patient perspective and experience, driven by their own patient journeys. Lived experiences often form evidence that cannot be captured through research which, by definition relies on sampling. Turning the research lens on oneself requires applying something technical to an experience that is emotional and unquestionably biased. The value? A novel unit of analysis-the continuum of care in its entirety-only accessible to the patient, which has the potential to uncover not only the answers that we haven’t yet found, but also the questions we haven’t yet asked. Questions such as: what are the strategies that patients use to navigate aspects of their care continuum, such as managing information? How do patients prioritise which questions and concerns to bring up with their care team (versus what is left unsaid)? How much work is involved in navigating illness, and further, how does “normal” work shift to others-e.g. household and childcare responsibilities? Representing this work across space and time is necessary to capture care continuity, along with identifying the opportunities for support. Specifically, the challenges and gaps that come to light via such representation (e.g. the fact that my oncologist did not tell me about chemo brain) are opportunities to improve or create education, more effective communication processes, and technological tools and interfaces to help with planning, scheduling, and information management.

And what of the covid-19 pandemic? A positive impact has been the relief of the burden of care through telehealth visits, and information sharing using means other than face-to-face. However, covid’s impact has included care delays, as well as a tremendous increase in “patient work’-for example, through managing logistics in the midst of uncertainty, and covid testing before procedures, just to name a few. It’s also been vital to make sure that, as far as possible, in-person visits continue for certain physical and visual examinations that are essential for safe and effective decision making by clinicians. Capturing one’s care continuum in this way is, I believe, an opportunity to shine the light on the remarkable amount of time and effort that is associated with a disease like early-stage breast cancer (where treatment intent is no evidence of disease [NED] status). Even more, identifying gaps and research questions, through this exercise, is a chance to potentially find meaning and purpose in a journey marked with uncertainty and fear. Both are necessary to move the science forward.

(10). Dwyer ER, et al. Who should consume high-dose folic acid supplements before and during early pregnancy for the prevention of neural tube defects? BMJ 2022;377:e067728.

What you need to know

Guidelines recommend 0.4mg of folic acid per day in the periconceptional period, and certain guidelines recommend high doses (4-5mg/day) in women at higher risk for neural tube defects such as those with diabetes, body mass index ≥30, or taking antiepileptic medications or other folate antagonists.

For those who had a previous pregnancy affected by neural tube defect, high quality evidence from a large randomised clinical trial supports using 4mg per day of folic acid

We lack evidence to suggest that high doses have additional benefit in preventing neural tube defects in women with other risk factors

Discuss with your patient their preference considering risk factors and the lack of evidence on benefits or harms of high dose folic acid to choose an appropriate dose

(11). Ananthakrishnan AN. Upadacitinib for ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2022;399(10341):P2077-2078.

The medical management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has been evolving at an exponential pace over the past decade, moving from the availability of only tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitors (anti-TNFα) in 1998, to the present where biologics or small molecules targeting at least five distinct mechanisms are available.

In The Lancet, Silvio Danese and colleagues report the results of induction and maintenance trials for upadacitinib, a selective inhibitor of the Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) enzyme, within the broader JAK enzyme family. These phase 3 trials randomly assigned patients with moderate-to-severely active ulcerative colitis to upadacitinib 45 mg orally daily (first induction study: n=319, 121 [38%] women, median age 43.0 [IQR 23.0]; second induction study: n=341, 127 [32%] women, median age 40.0 [24.0]) or placebo for 8 weeks (first induction study: n=154, 57 [37%] women, median age 44.5 [23.0]; second induction study: n=174, 67 [39%] women, median age 42.0 [24.0]). Responders were re-randomly assigned to maintenance doses of upadacitinib 15 mg (n=148, 53 [36%] women, median age 40.0 [22.0]) or 30 mg (n=154, 68 [42%] women, median age 41.0 [7.0]) orally daily or placebo (n=149, 64 [43%] women, median age 40.0 [21.0]) for an additional 52 weeks. The primary endpoint was clinical remission at 8 weeks (inductions studies) and 52 weeks (maintenance study), with key secondary endpoints of endoscopic remission, clinical response, and histological–endoscopic mucosal improvement. In the two induction studies, patients receiving upadacitinib were significantly more likely to attain clinical remission (26% and 34%) compared with placebo (5% and 4%, respectively). Similarly, during maintenance, there were higher rates of clinical remission after 52 weeks with both the 15 mg (42%) and 30 mg (52%) of upadacitinib compared with placebo (12%). Based on these results, upadacitinib was approved for treatment of ulcerative colitis by the US Food and Drug Administration in March, 2022.

(12). Hong-Li Z, et al. Is a Shaking Hand or a Trembling Heart Producing Changes in Electrocardiogram Findings? JAMA Intern Med. 2022.

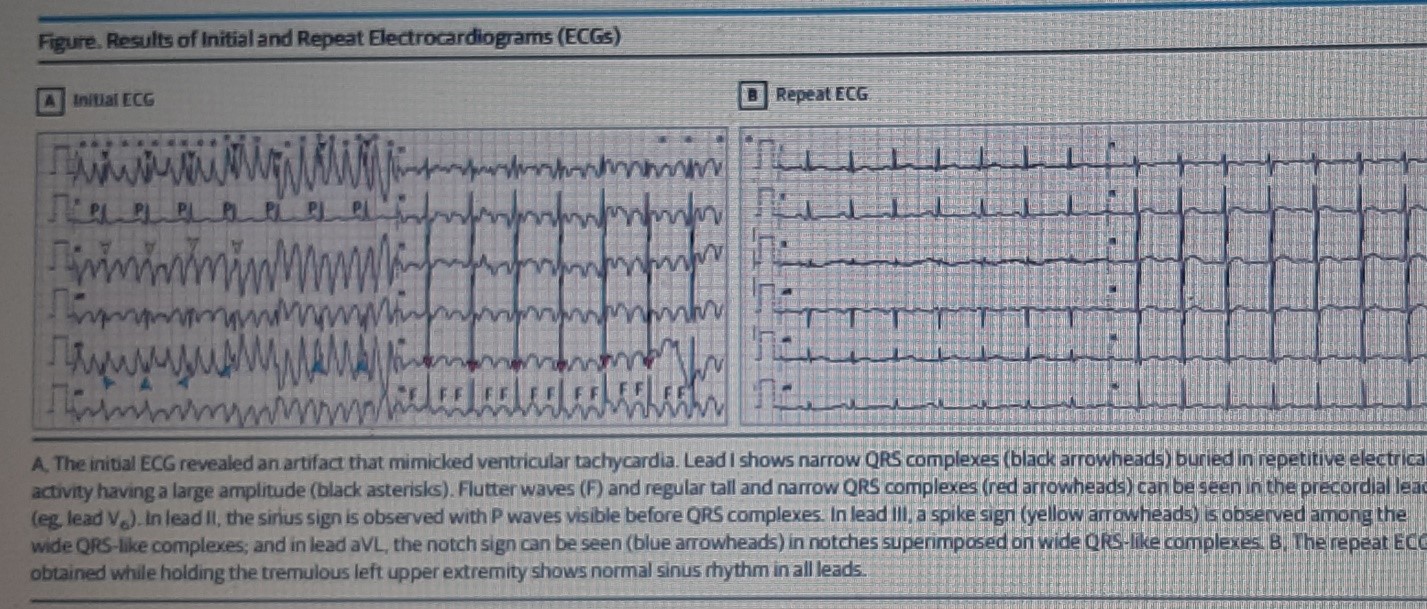

An individual in their early 70s presented to the emergency department with dizziness and weakness in bilateral lower limbs for 7 days. The patient had a 7-year history of hypertension; a 10-year history of diabetes; and denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. The patient had bradykinesia, left-hand tremor, and postural instability. At admission, blood pressure and pulse rate were 149/76 mm Hg and 92 beats per minute, respectively. Laboratory results (hemogram, serum electrolytes, kidney and hepatic function tests, and D-dimer levels) were all within normal limits. An electrocardiogram (ECG) was obtained on admission (Figure, A).

(A). The initial ECG revealed an artifact that mimicked ventricular tachycardia. Lead I shows narrow QRS complexes (black arrowheads) buried in repetitive electrical activity having a large amplitude (black asterisks). Flutter waves (F) and regular tall and narrow QRS complexes (red arrowheads) can be seen in the precordial leads (eg, lead V6). In lead II, the sinus sign is observed with P waves visible before QRS complexes. In lead III, a spike sign (yellow arrowheads) is observed among the wide QRS-like complexes; and in lead aVL, the notch sign can be seen (blue arrowheads) in notches superimposed on wide QRS-like complexes.

(B). The repeat ECG obtained while holding the tremulous left upper extremity shows normal sinus rhythm in all leads.

On initial evaluation, the emergency department resident suspected that the patient had ventricular tachycardia (VT). However, the patient did not have palpitations or hemodynamic instability; heart sounds and pulse rate were normal; and pulse oxygen saturation waveform showed that the ventricular activity had a normal rate. The senior clinician suggested holding the patient’s tremulous left upper extremity while obtaining a repeat ECG (Figure, B).

Question: What is the explanation for these ECG findings?

Interpretation

The ECG at admission revealed a narrow QRS complex rhythm (sinus rhythm) in lead II, while the remainder of the limb leads demonstrated wide QRS complex tachycardia consistent with VT. Lead I clearly shows narrow QRS complexes (black arrowheads) buried in repetitive electrical activity having a large amplitude (black asterisks). Flutter waves (F) and regular tall and narrow QRS complexes (red arrowheads) can be seen in the precordial leads (eg, lead V6). Results of a repeat ECG showed normal sinus rhythm.

In fact, these ECG changes were caused by muscular tremors of the left upper extremity. This type of tremor is common in patients with Parkinson disease, and when a tremulous extremity is held still or the limb electrode is moved to the torso, these pseudo-waves disappear. This patient was diagnosed with acute cerebral infarction and Parkinson disease. After conservative treatment, the condition improved, and the patient was discharged from the hospital.

Discussion

Electrocardiographic artifacts are defined as ECG abnormalities caused by sources other than the electrical activity of the heart. Artifacts are observed commonly in the ECGs of patients requiring evaluation and monitoring in the prehospital, emergency department, or intensive care unit settings. In general, sources of ECG artifacts can be divided into 2 categories: physiological and nonphysiological. Physiological sources may involve muscular activity (eg, tremors, shivering, convulsions) and patient motion. All muscle contractions are initiated by the flow of electrically charged ions. This electrical flow produces a signal that appears on the ECG as rapid spikes arising simultaneously with the muscle contraction.

The typical parkinsonian tremor has a frequency of 4 to 6 Hz or 240 to 360 times per minute at rest, similar to atrial flutter and VT. Therefore, electrical activity of the tremors can mimic VT when the voltage of artifacts is high, and atrial flutter when the voltage of artifacts is low. This patient’s ECG changes (Figure, A) were caused by muscular tremors that resembled VT in the limb leads (except lead II) and atrial flutter in the precordial leads. Misinterpreting these artifacts can mean unnecessary or even dangerous treatment or intervention. Careful analysis of these signals usually helps to find the source of the artifact, which can then be eliminated.

According to the Einthoven triangle theory, lead I compares the electrical differences between the right and left arms; lead II, between the right arm and left leg; and lead III, between the left arm and leg. Therefore, when the muscular tremors originate from the left arm, the lead formed between the right arm and left leg (lead II) remains normal. Similarly, when the muscular tremors originate from the right arm, the lead formed between the left arm and leg (lead III) remains normal. When the muscular tremors originate from the left leg, the lead formed between the left and right arms (lead I) remains normal. In addition, limb tremors can affect the precordial leads because the central terminal, which constitutes the negative pole of the unipolar leads, is produced by connecting the 3 limb electrodes via a simple resistive network to provide an average potential across the body.4 Therefore, only 1 limb lead (I, II, or III) will remain unaffected when a single limb is the source of the muscular tremors. This is the most important and simplest method for detecting the ECG interference caused by muscular tremors originating from a single limb.

In this patient, the left arm tremor was the source of the artifacts; therefore, lead II showed normal rhythm (Figure, A). In addition, the rate of suspected VT in this patient was approximately 300 per minute, and R waves were visible through the abnormal rhythm in lead I, which further demonstrated that the suspected VT was actually pseudo-arrhythmia.

Huang and colleagues have described 3 signs that can help differentiate VT from pseudo-VT. The presence of any of these elements is indicative of pseudo-VT: (1) sinus sign, 1 lead among leads I, II, and III showing sinus rhythm; (2) spike sign, the presence of small regular or irregular peaks between wide QRS complexes; and (3) notch sign, overlapping notches in the artifact coinciding with the sinus cycle length. In the ECG results of this patient, all 3 characteristics were present (Figure, A).

Take-home Points

Muscle contraction generates electrical signals that can produce ECG artifacts.

Any ECG artifact produced by typical parkinsonian tremor may simulate atrial flutter or VT.

Holding the tremulous extremity or moving the limb electrode to the torso can reduce or eliminate ECG artifacts.

Pseudo-VT may be indicated by any 1 of 3 signs: sinus, spike, and/or notch signs.

Pseudo-VT may also be indicated by clinical characteristics, eg, absence of palpitations or hemodynamic instability, normal heart sounds and pulse, and a normal pulse oxygen saturation waveform.

(13). Victor Ariel J, et al. What is the role of minimally invasive surgical treatments for benign prostatic enlargement? BMJ 2022;377:e069002.

What you need to know

New minimally invasive surgical treatments for benign prostatic enlargement that do not use spinal or general anaesthesia are available for patients experiencing lower urinary tract symptoms

Some of these procedures may offer similar improvement in symptoms as traditional surgery, with fewer adverse events, but the evidence is of low to very low quality, short term, and insufficient

Refer patients whose condition does not improve with conservative measures and medications to a urologist to discuss surgical options, considering benefits and possible complications, effect on sexual function, and need for retreatment

Benign prostatic enlargement (BPE), also called benign prostatic hyperplasia, is a common cause of lower urinary tract symptoms in men over 50. Increased frequency or urgency of urination, nocturia, difficulty starting urination, or dribbling at the end of urination, are common symptoms.1 BPE is characterised by growth of glands and smooth muscle parts of the prostate and is separate from prostate cancer. In later stages, it can result in bladder outlet obstruction with complications including urinary retention, infection, and possibly impaired renal function.

Initially, if no complications are evident, patients are advised conservative measures such as reducing the amount of fluid intake in the evening, and medications, including α blockers and 5-α reductase inhibitors.2 Surgical ablation to reduce the physical obstruction caused by BPE is an option if symptoms do not improve, patients experience side effects (for example, orthostatic hypotension, which can occur with α blockers, or sexual adverse events with 5-α reductase inhibitors) or do not prefer to take medications long term.

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is the mainstay of surgical treatment.2 This involves shaving off inner sections of the prostate with an electric loop under direct vision of a cystoscope.

(14). Smith R. Perhaps medicine is best understood when it confronts death. BMJ 2022;377:o1415.

Until the 16th century it was not an aim of doctors to try and hold back death. God, in all his and her various manifestations, decided when people should die. It was not for doctors to get in the way of death. Indeed, to try and do so would be to insult God.

The Renaissance philosopher and scientist Francis Bacon (1561-1626) was the first to argue that it should be one of the tasks of doctors to battle with death. But it was not until the middle of the 20th century that medicine developed effective means to delay death.

Since then, medical research has been much more concerned with diseases like cancer and cardiovascular disease that are major causes of death than with conditions like depression and musculoskeletal and skin diseases more associated with suffering than death.

(I remember hearing an American psychiatrist argue that psychiatry made a strategic mistake in not emphasizing more that severe mental health problems are an important cause of premature death.)

Death attracts more research funding than suffering.

Ironically, the medical specialty most associated with death, palliative care, attracts only paltry research funding because it is concerned with accepting death not defeating it.

Is medical research out to defeat death? Certainly, large sums are being invested in dramatically extending life if not in defeating death altogether. Much of this investment is on the West Coast of the US where all of life’s problems, including death, are seen as solvable with enough money and genius. Conventional medical research is not aiming explicitly at defeating death, but implicitly it seems to be: it is aiming at curing all diseases.

Medicine’s implicit mission to defeat death provides the context when a doctor meets a patient with a life-threatening disease.

At its heart is patients thinking doctors to have greater powers than they actually possess and doctors being painfully aware of the limitations of their craft but being reluctant to be fully open about those limitations.

For patients it’s wonderful to believe that doctors can fix most of their ills. For doctors the gap between what patients wish they could do and what they can do is uncomfortable, but doctors may worry that a full confession may limit their therapeutic power and perhaps their status and income. The media contribute to this in that they prefer tales of what look like medical miracles to medical disasters.

When patients with life-threatening illnesses consult doctors, they hope, or may even believe, that the doctors will be able to hold off, or defeat death. The doctors make their assessment and let us suppose for this discussion that they think that there is a 10% chance that they can keep the patients alive for five years. The doctors know that the patients will suffer great discomfort during the treatment and have a 90% chance of dying within a few years or even months.

What should the doctors say? To the rational person, perhaps an economist, it seems simple: the doctors should present all the options with as much information as possible. If a patient says, “You do what you think best, doc,” the doctor should say, ‘I can’t do that. This is your life. You are a unique individual you must decide, probably after talking to family and friends.”

Such conversations are rare. These are emotionally-charged encounters with death watching both patients and doctors. Patients want to hear that doctors can cure them, quickly and with minimal pain and discomfort. The doctors know what the patients want to hear, but will know that cure is highly unlikely, probably impossible, and that the treatment will be prolonged and involve much discomfort. The doctors wish that they could do more and may be attracted by new treatments of uncertain benefit.

The conversation that needs to happen has been called “the difficult conversation,” although others prefer ‘the anticipatory or essential conversation.’ We know that it often doesn’t happen, and the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death (which I cochaired) lists many reasons why the conversations don’t take place: busy clinics; fear of extinguishing hope or creating despair; difficulties finding the right language; the fix-it, protocol-driven culture of much of medicine; lack of clarity about whose job it is to start and hold the conversation; and perhaps even cowardice.

It is easier for both doctors and patients to launch into a conversation about the treatments available and how they will be given and then begin the treatment. One result is that patients can be days or even hours from death without either the patients or their families aware that the patients are about to die. Another possibility is that the palliative care team is asked to come and hold the conversation that should have taken place weeks or month before.

The myth patients believe that doctors can do more than they can and doctors go along with the belief is highly-I might even say fatally-attractive to both patients and doctors.

But ultimately it causes excess suffering for patients and infantilises them, while doctors are left with the discomfort of being evasive, dishonest, or cowardly.

This also explains why, as the Lancet Commission found, 10% of annual health expenditure is spent on the 1% who die in that year.

It takes courage from both patients and doctors to move beyond the myth in all of healthcare, but especially when death is close, but everybody-patients, doctors, other health professionals, citizens, and taxpayers-stand to benefit.

(15). Basil Sharrack et al. Is stem cell transplantation safe and effective in multiple sclerosis? BMJ 2022;377:e061514.

What you need to know

Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (aHSCT) is a relatively new treatment for patients with highly active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) that has not responded to treatment with disease modifying therapies

Very limited evidence from two small randomised controlled trials shows that aHSCT may slow disease activity and disability progression in some patients, but it is not known how this compares with newer, highly effective disease modifying therapies

Patients with highly active relapsing-remitting MS can be considered for aHSCT in specialist centres, and should be treated as part of a clinical trial or included in registry studies

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immune mediated disease of the central nervous system. It can lead to visual, sensory, and motor impairment, and difficulties with balance and sphincter control. More than 130000 people in the UK, and more than 2.5 million people worldwide, are affected. MS is an important cause of disability in young adults, with most being diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 40.

Most patients (85%) have a relapsing-remitting (RR) clinical course (RRMS), with episodes of new or worsening symptoms, known as relapses, which improve or resolve over weeks or months. This is followed by periods of remission, with or without persistent disability. Disease modifying therapies (DMTs) are offered as standard treatment to patients with active relapsing-remitting disease. Highly effective DMTs result in NEDA (no evidence of disease activity), defined as the absence of clinical relapses, disability progression, or disease activity visible on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), in 34-48% of patients at 2 years. Over time, most patients with RRMS (50% at 10 years) transition to a secondary progressive course, where disability increases gradually. A smaller proportion of patients with MS (10-15%) have a primary progressive course from onset, with worsening disability independent of relapses.

(16). Palmore TN, et al. Adding New Fuel to the Fire: Monkeypox in the Time of COVID-19: Implications for Health Care Personnel. Ann Intern Med. 2022.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to challenge health care workers around the world, monkeypox virus is reemerging, with 1233 confirmed cases reported on 6 continents as of 8 June 2022. As the monkeypox outbreak grows, health care workers must understand the threat and be prepared to address an infectious disease risk that may herald yet another unprecedented epidemic.

Monkeypox virus is an enveloped double-stranded DNA virus that belongs to the Orthopoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family, which includes variola (smallpox virus), vaccinia (the smallpox vaccine virus), and cowpox virus. Monkeypox is endemic in western and central Africa. Outbreaks have been smoldering there for years, with cases occasionally imported to the United States and Europe. Although smallpox has significant risk for airborne spread, monkeypox is transmitted via direct contact with body fluids from an infected person, through contact of mucosal surfaces or nonintact skin with open lesions, via respiratory droplets, or through contact with contaminated objects. The disease is believed to become infectious at symptom onset.

Past human monkeypox infections detected in the United States have almost invariably been related to travel from endemic areas, exposure to infected animals imported from endemic areas, or exposure to domestic animals infected by imported animals. In contrast, the current outbreak has to date affected primarily young men who have sex with men (MSM). Genome sequencing has shown that the isolates belong to the less virulent of the 2 circulating monkeypox clades, with previous mortality of 1% or less.

Guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention can help clinicians to safely manage a suspected case of monkeypox infection in a health care setting. Health care workers should wear personal protective equipment (PPE) that is appropriate for airborne precautions, including a fit-tested filtering facepiece respirator (for example, an N95 respirator) or a powered air-purifying respirator. State and local health departments should be informed immediately to assist in testing.

Poxviruses are very stable and may remain contagious over months to years in the environment. They are highly resistant to desiccation and heat, and this is accentuated by their inclusion in protected environments (such as dermal crusts), with implications for hospital infection control. Approved disinfectants should be used for cleaning and disinfection of high-touch surfaces, and procedures (such as sweeping, dry dusting, or shaking bed linens) that may aerosolize virus particles should be avoided. Linens should be removed carefully and washed at high heat or discarded.

Careful history taking and contact tracing are essential. Patients may have had multiple visits to health care facilities or an extended stay in a facility with multiple personnel contacts before monkeypox infection was suspected and appropriate precautions were implemented. Infection prevention and infectious diseases staff should work closely with public health and occupational health services to facilitate case investigation. Although monkeypox has caused occupational infections among health care workers who were not wearing PPE, timely postexposure vaccination and close monitoring help to reduce further spread of infection.

In this epidemic, clinical presentations have frequently been atypical, mimicking some sexually transmitted infections by presenting with genital, groin, perianal, or rectal lesions and, in some cases, painful inguinal adenopathy. Although genital lesions have also been described in endemic cases, reports from this outbreak suggest that the febrile prodrome that characterizes classic monkeypox disease has been mild or absent in some cases. Each exposed health care worker needs to undergo detailed risk assessment to determine exposure and receive counseling on self-monitoring, isolation, and prompt reporting of symptoms based on risk level. For example, a nurse who shakes an infected patient’s bed linens is likely at higher risk (from aerosolized virus particles) than a nurse who takes vital signs and administers medications.

Although waves of COVID-19 have at times decimated health care staffing, appropriate caution will prevent monkeypox from adding to staffing shortages. Exposed health care workers need not quarantine but should undergo active surveillance during the 21-day incubation period, including twice-daily temperature checks and daily occupational health symptom screening before reporting to work. Educating health care workers and the public may help reduce delays in diagnosis and limit exposures.

Given the characteristics of the current outbreak, patients with monkeypox infection may present to sexually transmitted infection clinics or other outpatient settings that are not well equipped for isolation procedures. Such settings need to be vigilant for potential cases and have appropriate PPE available.

Sadly, monkeypox has been endemic to Africa for years, with insufficient attention from the rest of the world. Now we are facing infections on every inhabited continent at a time when clinical and public health resources have been stretched to the limit by COVID-19. The public is weary of risk mitigation and the need to be cautious. Public health workers and health care workers are exhausted. The prospect of addressing a new communicable pathogen may add to their existing stress and should be acknowledged and mitigated whenever possible. Efforts to alleviate the added stress of a new communicable pathogen are essential.

Although monkeypox is unlikely to reach the pandemic spread of COVID-19, physicians and other health care workers must be vigilant, with a high index of suspicion and careful adherence to appropriate infection control precautions as the outbreak unfolds. Importantly, the infection control response must avoid stigmatizing the most affected patient population and should instead ally itself with the MSM community to combat monkeypox.

Infection prevention teams and infectious diseases staff should also take advantage of relationships with public health departments fortified over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Leveraging these ties to improve communication, to muster resources, and to work in concert with affected communities will give us the best chance of quelling monkeypox.

(17). Yi-Wei C, et al. Cause of Recurrent Syncope in an Elderly Patient. JAMA Intern Med. 2022.

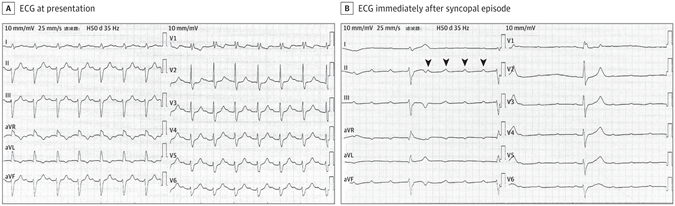

Aman in his 80s with recurrent syncope was admitted to the emergency department. The patient previously underwent an electrophysiological study (the exact procedure was unknown) in another hospital because of syncope, and the result did not suggest the need for pacemaker implantation. He denied a recent medical history of chest pain or dyspnea on exertion. On examination, his oxygen saturation while breathing room air was 98%, and his blood pressure was 120/76 mm Hg. The result of cardiopulmonary examination was unremarkable. Echocardiogram findings revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 54% with normal ventricular wall motion. Blood laboratory data, including serial high-sensitivity troponin, D-dimer, renal function, electrolytes, and blood glucose, were unremarkable. The results of the electrocardiogram (ECG) that was performed at admission was recorded (Figure, A).

(A) ECG at presentation showed sinus rhythm (89 bpm), a prolongation of PR interval to 304 milliseconds, right bundle branch block, and left anterior fascicular block. B, ECG obtained immediately after the syncopal episode showed atrioventricular dissociation with a sinus rate of 102 bpm and a ventricular rate of 22 bpm. The arrowheads indicate wide QRS complex (duration 164 ms) with right bundle branch block morphology and left deviation of electrical axis.

Questions: What is the ECG finding? What is the possible cause of syncope? What is the management strategy?

Interpretation and Clinical Course

The ECG at presentation (Figure, A) showed sinus rhythm (89 beats per minute [bpm]), a prolongation of PR interval to 304 milliseconds, right bundle branch block (RBBB), and left anterior fascicular block (LAFB). These features suggest first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block with bifascicular block. The patient experienced syncope again during cardiac monitoring in the emergency department, and an ECG was performed immediately (Figure, B). The ECG (Figure, B) showed AV dissociation with a sinus rate of 102 bpm and a ventricular rate of 22 bpm. The results showed wide QRS complex (duration 164 milliseconds) with RBBB morphology and left deviation of the electrical axis. The presence of AV dissociation can be diagnosed as complete AV block. During this period of hospitalization, this elderly patient underwent dual-chamber permanent pacemaker implantation. The patient had no recurrence of syncope attacks during the 18-month follow-up period after discharge.

Discussion

Bifascicular block is a conduction disorder that has a reported prevalence of 1% to 1.5%, including complete left bundle branch block or RBBB with either LAFB or left posterior fascicular block. Bifasicular block may be accompanied by residual functional bundle lesions, and there is a risk of progression to complete AV block. In this case, the elderly patient’s baseline ECG showed bifascicular block (RBBB and LAFB) and left posterior fascicle (the residual) working (was functional). The incidence of bifascicular block progressing to complete AV block is 1% to 6% each year. A study showed that 10% to 15% of patients with bifasicular block may experience syncope within 3 years. The potential causes of syncope are heterogeneous, but intermittent complete AV block is a frequent cause. In this case, complete AV block was recorded when the elderly patient with bifasicular block experienced syncope again in the emergency department. The patient did not develop any episodes of syncope after dual-chamber pacemaker implantation, confirming that syncope was associated with intermittent complete AV block.

It is worth noting that bifascicular block with first-degree AV block is not trifascicular block, which is a common misdiagnosis. Trifascicular block indicates disease in all 3 fascicles (right bundle branch, left anterior fascicle, and left posterior fascicle). First-degree AV block (PR interval lengthening) may represent conduction delay at the AV node level rather than the level of the intraventricular fascicles. Prolongation of the PR interval may also be intra-Hisian in addition to AV node level. In patients with bifascicular block, the prolongation of the PR interval increases the possibility of the only functional bundle conduction disease of His-Purkinje. Bifascicular block combined with a prolonged PR interval is related to high rates of complete AV block and mortality in the elderly.

Intermittent complete AV block is a common underlying cause of syncope in patients with bifascicular block. According to a recent guideline on cardiac pacing, electrophysiological study should be considered after noninvasive assessment for patients with bifascicular block and unexplained syncope. Electrophysiological study includes the measurement of His bundle-ventricular (HV) interval at baseline, with stress by incremental atrial pacing. In patients with bifascicular block and unexplained syncope, the pacemaker should be considered in the presence of an HV interval of 70 milliseconds or longer or second- or third-degree intra- or infra-Hisian block by incremental atrial pacing. A electrophysiological study has a positive predictive value of 80% for identifying AV block. However, a negative electrophysiological study cannot exclude intermittent AV block. In fact, in patients with negative electrophysiological study results, approximately 50% of cases were recorded by an implantable loop recorder as intermittent or stable AV block. In this patient, although the electrophysiological study results were negative (no indication of pacemaker implantation), intermittent complete AV block was recorded on resting ECG. Empirical pacemaker implantation may benefit elderly patients with bifascicular block and unexplained syncope, especially in the event of unpredictable and recurrent syncope. Therefore, in the absence of electrophysiological study results, pacemaker implantation can be considered in specific patients with bifascicular block and unexplained syncope (elderly, frail patients, or those with recurrent syncope).

Intermittent complete AV block is a common underlying cause of syncope in patients with bifascicular block. This case emphasizes that for patients with bifascicular block and syncope, intermittent AV block cannot be ruled out even if the electrophysiological study is negative. Elderly patients with bifascicular block and unexplained syncope may benefit from empirical pacemaker implantation, especially in recurrent and unpredictable syncope that puts patients at high risk of traumatic recurrences.

Take-home Points

Patients with bifascicular block may also have residual functional bundle lesions and be at risk for the development of complete AV block.

Intermittent complete AV block is a frequent cause of syncope in patients with bifascicular block.

A negative electrophysiological study cannot exclude intermittent AV block as the cause of syncope.

Pacemaker implantation can be considered in specific patients with bifascicular block and unexplained syncope (elderly, frail patients, or those with recurrent syncope) without electrophysiological study results

(18). Bell KJL, et al. Evaluation of the Incremental Value of a Coronary Artery Calcium Score Beyond Traditional Cardiovascular Risk Assessment: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(6):634-642.

Question: Is there an incremental gain from the addition of a coronary artery calcium score (CACS) to a standard cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk calculator?

Findings: In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the pooled gain in C statistics from adding CACS was 0.036. Most participants reclassified as being at intermediate or high risk by CACS did not have a CVD event during follow-up (range, 5.1 to 10.0 years).

Meaning: Although CACS appears to add some further discrimination to standard CVD risk calculators, no evidence suggests that this provides clinical benefit.

Importance: Coronary artery calcium scores (CACS) are used to help assess patients’ cardiovascular status and risk. However, their best use in risk assessment beyond traditional cardiovascular factors in primary prevention is uncertain.

Objective: To find, assess, and synthesize all cohort studies that assessed the incremental gain from the addition of a CACS to a standard cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk calculator (or CVD risk factors for a standard calculator), that is, comparing CVD risk score plus CACS with CVD risk score alone.

Evidence Review: Eligible studies needed to be cohort studies in primary prevention populations that used 1 of the CVD risk calculators recommended by national guidelines (Framingham Risk Score, QRISK, pooled cohort equation, NZ PREDICT, NORRISK, or SCORE) and assessed and reported incremental discrimination with CACS for estimating the risk of a future cardiovascular event.

Findings: From 2772 records screened, 6 eligible cohort studies were identified (with 1043 CVD events in 17961 unique participants) from the US (n=3), the Netherlands (n=1), Germany (n=1), and South Korea (n=1). Studies varied in size from 470 to 5185 participants (range of mean [SD] ages, 50 [10] to 75.1 [7.3] years; 38.4%-59.4% were women). The C statistic for the CVD risk models without CACS ranged from 0.693 (95% CI, 0.661-0.726) to 0.80. The pooled gain in C statistic from adding CACS was 0.036 (95% CI, 0.020-0.052). Among participants classified as being at low risk by the risk score and reclassified as at intermediate or high risk by CACS, 85.5% (65 of 76) to 96.4% (349 of 362) did not have a CVD event during follow-up (range, 5.1-10.0 years). Among participants classified as being at high risk by the risk score and reclassified as being at low risk by CACS, 91.4% (202 of 221) to 99.2% (502 of 506) did not have a CVD event during follow-up

Conclusions and Relevance: This systematic review and meta-analysis found that the CACS appears to add some further discrimination to the traditional CVD risk assessment equations used in these studies, which appears to be relatively consistent across studies. However, the modest gain may often be outweighed by costs, rates of incidental findings, and radiation risks. Although the CACS may have a role for refining risk assessment in selected patients, which patients would benefit remains unclear. At present, no evidence suggests that adding CACS to traditional risk scores provides clinical benefit.

(18). Reynolds AC. How can I help my children understand my chronic autoimmune conditions and their management? BMJ 2022;377.

I live with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). Over the past two years, particularly with the uncertainty around covid-19 for immunocompromised patients, I realised that I had rarely included my children directly in conversations about my health.

My health conditions are largely invisible, which can be both a blessing and a challenge. To my children, their mama looks just as “well’ as other parents they meet. However, when a flare or acute illness presents, some of the health challenges are very visible and frightening for my children, as it must be for others who have a parent living with a lifelong, chronic condition.

My children have helped me with calling an ambulance, and have seen me acutely unwell in the emergency department on more than one occasion. One particular event distressed my young son so much that there were a lot of tricky questions afterwards that we needed to navigate: “Will this go away for you?,” “Are you going to die?,” “Will this happen to me too?”

This experience made me consciously reflect on conversations we have with children, particularly young children, about their parents managing chronic conditions. How much information should I give them? How do other parents with chronic autoimmune conditions have these conversations with their children? How can I be honest about my health, without frightening them?

While new studies of diagnosis and management are critical for conditions like mine, so too are studies that support patients to best live the lives we have right now. For me, involving and supporting my children are central to this. The inspiration for this piece came courtesy of an episode of children’s TV programme Operation Ouch, where a demonstration of viper venom and a blood sample was central to a conversation about clots. My daughter played the segment for me on her iPad, with the question, “Mum! Is this what happens to your blood?”

She asked me to show her the medication that manages clotting, and this extended to a broader conversation about the other medications I take. Finally, she asked if she could help me by sorting my medications (under supervision) into the weekly pill organiser I use. She asks about doses, changes in colour, and type. Like clockwork every Friday night, she reminds me of her chosen job. I can’t say I would have planned explicitly to include her in this way, but it makes her feel she is involved, helping, and informed-and that seems to be really valuable to her at this age.

To an extent, my conversations (and increasingly inclusive approach to my health) with my children have been ad hoc. Looking back, I would have welcomed ideas from other patients about how to start these conversations, particularly before major events prompted distress and uncertainty for my children. I still do, as I don’t know what is to come.

Qualitative research and insights from other patients living with my autoimmune condition, and their experiences of supporting their children across childhood and adolescence, would be invaluable. Existing literature suggests that living with a parent who has a physical or mental illness can impact quality of life and wellbeing in children. Many of these findings understandably focus on contexts that involve terminal illness or life-threatening conditions such as terminal cancer, or more recently, covid-19.

While these studies offer some insight into the experiences of parents and children in life threatening circumstances, they may not be as relevant to patients such as myself, who have lifelong chronic conditions. These perspectives are more limited. Considering these insights could add important context and support material for future parents navigating lifelong chronic conditions, particularly given associations with wellbeing and quality of life for the children themselves.

(19). Gue YX, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy in Atrial Fibrillation and Coronary Artery Disease, Does Less Mean More? JAMA Cardiol. 2022.

In the treatment of patients with chronic coronary syndrome, the use of antiplatelets in the form of aspirin is a class 1 indication in the prevention of future thrombotic events. Similarly, oral anticoagulation (OAC) has a class 1 indication for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and a CHA2DS2-VASc (congestive heart failure) score of 2 or more in males and a score of 3 or more in females in the form of a non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant (NOAC) for stroke prevention. However, the optimal choice of long-term antithrombotic therapy in patients with AF in the presence of coronary artery disease (CAD) has been subject to much debate. Striking the right balance between thrombotic and bleeding risk with different monotherapy or combination therapy with OAC and antiplatelet(s) remains a difficult task requiring the understanding of the dynamic nature and continual assessment of nonmodifiable and modifiable bleeding and thrombotic risk factors.

In this issue, the AFIRE investigators report a post hoc secondary analysis of the AFIRE trial (Antithrombotic Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation with Stable Coronary Disease). The AFIRE multicenter, open-label, randomized clinical trial, which was terminated early owing to the increased mortality in the combination group, compared rivaroxaban monotherapy with combination therapy (rivaroxaban plus a single antiplatelet agent) in patients with AF and stable CAD. The investigators found that rivaroxaban monotherapy was noninferior to combination therapy for the primary efficacy endpoint, a composite of stroke, systemic embolism, myocardial infarction, unstable angina requiring revascularization, or death from any cause (4.14% vs 5.75%, hazard ratio [HR], 0.72, 95% CI, 0.55-0.95; P<.001 for noninferiority) and superior for the primary safety end point of major bleeding (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.39-0.89; P=.01 for superiority).

Rather than the conventional time-to-first event analysis, the authors of this post hoc analysis used the total number of events as the primary end point over the study period, which was a median follow-up of 24.1 months. The results supported the findings of the initial analysis, rivaroxaban monotherapy demonstrated lower total event rates when compared with combination therapy (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.48-0.80; P<.001). When looking further into the different types of events, the authors found that first bleeding events are more clinically effective than first thrombotic events in terms of mortality risk and these occurred more frequently, regardless of the nature of the first event.

This study highlights several aspects of the treatment of patients with AF and CAD. First, the mean age of patients included in the study was 74 years, reflective of the aging population that we are currently seeing in our clinics. The benefits of antiplatelet therapy (in the form of aspirin) have been debated, especially in the 65 years and older population for both primary prevention and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. The results of Naito et al4 also highlight that a shift in focus toward the mitigation of bleeding risk would provide more pronounced clinical benefit within the aging population, with a less-is-more approach with regards to the choice of antithrombotics. However, this may not be applicable to patients who are at particularly high thrombotic risk, i.e., previous stent thrombosis, severe diffuse CAD, or extensive complex coronary stenting.

Second, the complexity of managing a multimorbid patient requires further thoughts into providing a more individualized approach, consistent with current approaches to AF management, which promotes a holistic and integrated care approach6 that has been associated with improved clinical outcomes. The dynamic nature of both bleeding and thrombotic risks in patients require a continual evaluation of risk (combination of clinical and biomarkers) and subsequent alterations to their therapy to achieve the optimal outcome.3 Although the use of clinical risk scores, such as predicting bleeding complications in patients undergoing stent implantation and subsequent dual antiplatelet therapy (PRECISE-DAPT) and Academic Research Consortium for High Bleeding Risk (ARC-HBR), could aid clinicians in identifying high-risk patients, most of these scores were developed and validated in the acute post-thrombotic event period. Furthermore, the lack of validation of these scores within the stable CAD population, with underrepresentation of older adults, may limit the discriminatory value in these patients.

Third, the study was conducted in Japan and it is increasingly recognized that bleeding risk, both with OAC and with antiplatelet agents, is increased in East Asian patients, compared with Western, predominantly White patients. The findings may, therefore, not be generalizable to other populations.

Additionally, the analysis of total event rates, separated into first and subsequent events, in both arms provides a more comprehensive view of the overall benefit and risk of the 2 approaches. The fact that bleeding events affect subsequent mortality more perhaps emphasizes the dilemma faced by clinicians after a bleeding event on how to optimally manage the subsequent antithrombotic regimen, which was not addressed by this study.

In conclusion, the use of OAC monotherapy in patients with AF and stable CAD appears to be effective and safe when compared with combination therapy with OAC and antiplatelets but will require an individualized approach. Validation of currently available risk scores is required in this group of patients with AF as it may aid the decision-making process.

(20). Torabi AJ, et al. A Young Man With Syncope. JAMA Cardiol. 2022.

A man in his early 20s presented with suspected syncope and shaking with no significant medical history. The patient fell asleep and his girlfriend tried to wake him, but he started shaking and slumped over on the ground. He denied confusion afterward but did not feel well with nausea, flushing, chest tightness, and a rapid heart rate. About 10 minutes later, he had a second syncopal episode for 2 to 3 minutes with more than 20 muscle jerks. On presentation at the emergency department, he was afebrile, blood pressure was 120/59 mmHg, heart rate was 85 beats per min, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per min, and oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. His cardiac examination revealed normal heart sounds with no murmurs.

The electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed early on arrival in the emergency department (Figure). Transthoracic echocardiography revealed an ejection fraction of 54%, mild right ventricular (RV) dilation (RV diameter, 4.1 cm), and no significant valvular abnormalities. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed no RV abnormalities and qualitatively normal RV function. Neurology consultation was obtained with concern for an epileptic seizure event surrounding the recurrent syncopal episodes. Brain magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalogram were obtained, both of which results were normal. On further questioning, patient reported having a second cousin with sudden cardiac death of uncertain etiology in his early 20s.

Diagnosis

Brugada type 1 syndrome with unexplained syncope

What to Do Next

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator

Discussion

The key to the correct diagnosis in this case was the ECG that was consistent with spontaneous Brugada type 1 morphology with more than 2-mm coved ST-segment elevation in leads V1 and V2 (Figure). Recognition of the Brugada type 1 pattern as a potential cause of cardio-arrhythmogenic syncope is important.