New Onset Refractory Status Epilepticus (NORSE)

Department of Emergency Medicine and Critical Care, Kauvery Hospital, Trichy-Cantonment, India

Background

Status epilepticus is a life-threatening emergency, especially if refractory. While immediate treatment of seizures is paramount, it is also important to establish the cause. Up to 20% of patients with refractory status epilepticus have a negative initial workup, these represent up to 60% of de novo refractory status epilepticus and most are previously healthy young adults and children. Such cases have been variously referred to as having new onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE) or idiopathic catastrophic epileptic encephalopathy. They have also been classified as ‘possible encephalitis’, since some have a preceding febrile illness and the diagnosis of autoimmune and infective encephalitis does not require an identified pathogen or antibody. NORSE is thought to be rather rare. Here we discuss a patient presenting with NORSE.

Case Presentation

A 15-years-old boy was brought to our ER with an alleged history of RTA – a fall from a bike, following a seizure spell. He was initially managed at an outside hospital and was intubated; CT brain taken at the outside hospital was normal.

He was referred to us for further management as the patient continued to have recurrent seizures without regaining consciousness for a period of 2 h until he arrived at our ER.

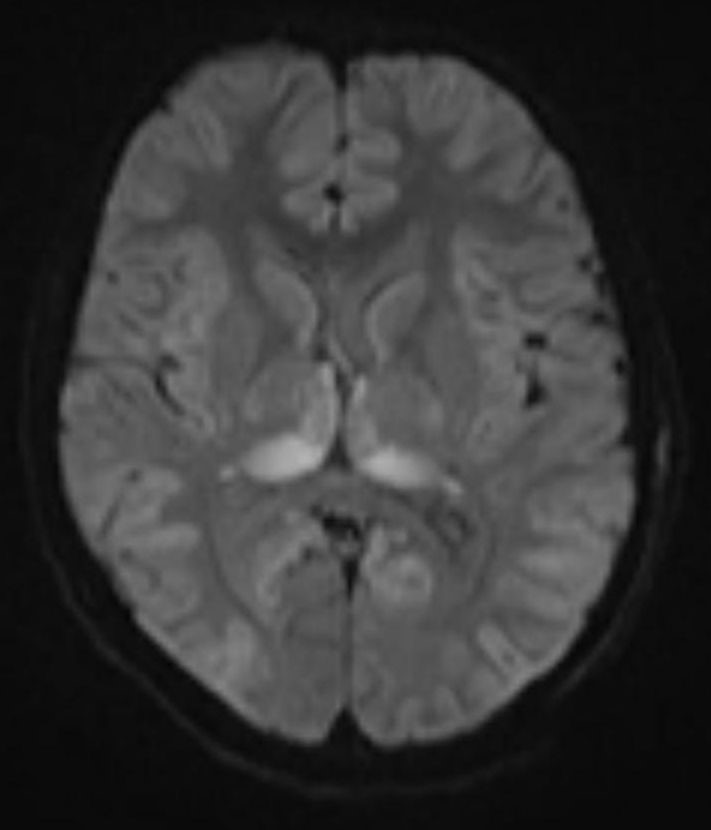

His GCS was E1V1M2 on arrival. He was managed with anti-seizure medications as a bolus and continued as iv infusions, along with iv fluids. He was sedated paralyzed and continued with mechanical ventilation. MRI Brain plain and contrast with whole spine screening showed T2/flair Hyperintensities in B/L medial temporal lobe, thalamus and periventricular cortex, B/L posterior parietal cortex with diffusion restriction and mass effect suggestive of viral encephalitis.

His initial labs showed leucocytosis (WBC: 29,800), normal renal parameters, and negative COVID RT-PCR.

He was shifted to the neuro intensive care unit for further management. Fever spikes were noted following admission.

CSF analysis showed lymphocytic pleocytosis, protein, 51.3; glucose, 73; WBC, 25; DC-polymorphs, 25%; Lympho-75%.

Total RBC: 3500.

CSF bacterial, viral, and autoimmune workups were all negative, JE workup was also negative; another systemic workup was negative.

EEG has done on day 8 was suggestive of encephalopathy, so new onset refractory status epilepticus secondary to encephalopathy or MISC was considered.

Features against MISC were fever presentation after the illness started which is rare in MISC, and the not significantly high Ferritin and COVID IgG levels.

He was empirically treated with anti-meningitic antimicrobials, multiple anti-epileptic drugs, and other supportive medications.

He was pulsed with steroid injection methylprednisolone 1 g OD for 5 days. Seizures slowly settled; AED infusion Midazolam was tapered and stopped on day 10 of admission and put on enteral route.

Tracheostomy was done to facilitate weaning and was gradually weaned off from NIV.

He showed very minimal improvement in his sensorium; his repeat MRI showed encephalitic changes.

He was discharged on tracheostomy, with nursing and physiotherapy care after 2 months of hospitalisation. On discharge, his GCS was E4 Vt M5.

Discussion

NORSE

New onset refractory status epilepticus is a condition, not a specific diagnosis, without a clear, acute or active, structural, toxic, or metabolic cause in a healthy patient without active epilepsy.

FIRES

FIRES is a subcategory of NORSE that requires a prior febrile infection, with fever starting between 2 weeks and 24 h prior to the onset of refractory status epilepticus, with or without fever at the onset of status epilepticus.

Status Epilepticus (SE)

It is defined as a prolonged seizure (>5 min if convulsive, >10 min if not) or a cluster of seizures without recovery in between. Status epilepticus that persists despite administration of at least two appropriately selected and dosed parenteral medications is termed Refractory status epilepticus (RSE). Most of the causes of RSE can be identified within 2-3 days of presentation, as it is commonly due to stroke or serious acute medical illness. In half of the cases, a cause is ultimately identified, most often autoimmune or paraneoplastic, followed by infections (mostly viral, although mycoplasma is not rare). In the remaining half or more, no cause is identified despite an extensive work-up. These cases are referred to as cryptogenic NORSE or NORSE of unknown etiology.

Incidence of NORSE

In the US, NORSE occurs in 7% of SE in 1/100000/year and it can occur at any age but most commonly affect young adults and school age children with a second peak occurring around age 65, females are more commonly affected than males

Causes of NORSE

The most common causes of NORSE are autoimmune or paraneoplastic disorders including anti-neuronal antibodies (anti-NMDA receptor), voltage-gated potassium channel complex, followed by viral encephalitis. These data are still very limited and further studies are required to fully explore the hypothesis of a genetic predisposition. These are referred to as cryptogenic NORSE or NORSE of unknown origin.

Symptoms and signs

The course of the syndrome begins as a mild fever, malaise, fatigue, and upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal infection. Two third of patients of NORSE sometimes hallucinate, apathy or agitation, and amnesia. Symptoms of meningeal inflammation such as headache and photophobia are uncommon.

Course

It starts as a complex partial seizure or grand mal seizure, intermittently and becomes increasingly more frequent, and the patient’s consciousness declines to status epilepticus. This acute phase lasts days to several weeks and may even last for several months. The mortality rate is up to 30% and is higher in adults than children, Once SE was controlled with antiepileptic drugs (AED) and continuous anaesthetic agents, they are subsequently discontinued once the seizure stops. The patients progressively regain consciousness and can be discharged from the hospital. But, half of the patients are left with long-time cognitive functional disorders and may have epilepsy lifelong, requiring AEDs.

Clinical testing and work up

The clinical workup should aim at identifying treatable causes of refractory SE. Brain CT and MRI scans are required to rule out stroke and other conditions with a characteristic appearance on imaging. In some cases of cryptogenic NORSE, brain MRI can reveal leptomeningeal enhancement, bilateral claustrum hyperintensity, or progressive mesial temporal lobe atrophy. Cerebrospinal fluid studies and blood tests should be performed to rule out infectious and inflammatory and autoimmune conditions. Kidney and liver function test, serum electrolytes to rule out metabolic conditions. Electroencephalography (EEG) and continuous EEG monitoring are usually required to detect and monitor and treat seizures.

Treatment

The treatment of SE initially consists of benzodiazepines (Lorazepam, Diazepam, or Clonazepam), followed by standard anti-seizure medication, as in most cases of SE. preference is given to drugs that are available in IV form (valproic acid, phenytoin, fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, Phenobarbital, llacosamide, and more recently brivaracetam).

The two options are either to try additional anti-seizure medications or to induce pharmacological coma with an anaesthetic drug. In the former case medications available in an IV formulation are often favoured but others (e.g. topiramate, pregabalin, clobazam, perampanel) are sometimes used later as add-on therapy via nasogastric tube.

Anesthetic agents utilized most commonly include infusions of midazolam, propofol, and barbiturates (pentobarbital in the USA and thiopental in Europe). Of the three, midazolam likely has the best safety profile but may be associated with a higher risk of recurrent seizures. Barbiturates are associated with more prolonged coma and the need for mechanical ventilation, with a higher rate of complications. propofol carries a small risk of propofol infusion-related syndrome (PRIS), a potentially lethal syndrome of metabolic acidosis, kidney and heart failure.

When an underlying cause is identified it should be appropriately treated.

There is currently no known specific therapy for cryptogenic NORSE and studies are urgently needed to determine the best treatment options.

Given the putative causal role of inflammation in cryptogenic NORSE, it is common to use approaches that modulate the immune system. These options include IV steroids, IV immunoglobulins, plasma exchange therapy (plasmapheresis), and some monoclonal antibodies against inflammatory cells (e.g. Rituximab). The efficacy of these strategies is suggested by small case series, though never investigated in controlled trials. Emerging therapies, such as anakinra (recombinant Il-1 receptor antagonist), tocilizumab (Il-6 receptor blocking humanized antibody), and cannabinoids have been used in NORSE, in case reports and small case series. The ketogenic diet, a therapy for chronic drug-resistant epilepsy, has shown some efficacy in both paediatric and more recently adult cases.

Conclusion

Status epilepticus is a medical emergency associated with significant mortality and morbidity. NORSE and FIRES are rare challenging presentation, comprehensive management includes early initiation of treatment, to prevent resistance to anti epileptics and extensive evaluation of etiology to treat the treatable causes, which includes autoimmune and paraneoplastic or metabolic causes these patients need to be treated in intensive care to continue second line drugs with ventilator support and EEG monitoring to prevent secondary brain insults.

Journals

- EDITORIAL

- Rare and complex type of MS, tumefactive multiple sclerosis

- Dilemma of decoding a difficult fever

- IMAGE CHALLENGE DIAGNOSTIC IMAGE

- PATIENT’S VOICE – A BOLT FROM THE BLUE

- THE UNIQUE MIND AN ANTHOLOGY OF POEMS

- EDITORIAL

- EDITORIAL BOARD

- SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Before Elective Surgery

- Evolution of Dashboards and its Effectiveness in Performance Management and Efficient Utilization of Time and Energy

- Anorexia Nervosa with Compulsive Exercising – A Case Report

- From the Desk of the Editor-in-Chief

- Section Editor

- PATIENT’S STORY

- The Un-Relished Performance

- THE ELECTRONIC MEDICAL JOURNAL OF KAUVERY HOSPITALS

- Vascular Covid Diaries

- Encephalitis – a success story

- Intracoronary imaging

- Patient’s Voice

- THE CURE BY KAANTHAL MANIKANDAN

- SEIZURE IN A NEWBORN

- SGLT 2 inhibitors in kidney disease

- Editor’s message – Dr Venkita S Suresh

- Preparing your manuscript

- Pulmonary valve endocarditis: a case report

- Upper limb replantations at different anatomical levels: a short case series Kiran Petkar

- Prevalence of vitamin B12, folate deficiency and homocysteine elevation in ASCVD or venous thrombosis

- HENOCH SCHOENLEIN PURPURA

- Life turns upside down for a young couple and family

- Vaccine Induced Cerebro Venous Thrombosis with Thrombocytopenia (VITT) – A Case Report

- Editor-in-Chief

- EDITORIAL

- Neurobiology of Romantic Love

- An interdisciplinary approach to treatment of juvenile OCD: a case report

- Fanconi Anaemia – Need to look at the whole picture

- The Art and Science of Preparation and Publication of Medical Research from Kauvery Hospitals

- FUNDAMENTALS OF STATISTICS

- Diagnostics Images

- A WAKE-UP CALL FROM THE ANAESTHESIOLOGIST, BY DR. VASANTHI VIDYASAGARAN

- A PATIENT’S STORY

- THE FALLACIES OF PERFECTION

- EDITORIAL

- EDITORIAL BOARD

- Difficult to Treat Epilepsy: A Management Primer for Non-Neurologists

- Clinical audit: A Simplified Approachs

- Rationalise and Restrict Antibiotic Use by Utilizing A Proactive Justification Form and Comparing with Earlier Antibiotic Usage in The Same Paediatric Unit in A Tertiary Care Centre

- COVID-19 and Fungal Infection – An Opportune Time: A Case Series

- Thymidine phosphorylase (TYMP) gene stop mutation, G38X, in a familial case of mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy

- Image Challenge

- PATIENT’S STORY

- ANTHOLOGY OF POEMS

- POEM

- POEM

- EDITORIAL

- EDITORIAL BOARD

- Hypertension – a renal disease

- A New Cause for Confusion or Concern – A Case Series

- A rare case of acute aortic dissection secondary to a penetrating aortic ulcer in the ascending aorta

- Pacemaker in children – big shoes to fill for small foot

- The Eight Roles of The Medical Teacher – The Purpose and Functions of a Teacher in The Healthcare Professions by Ronald M. Harden & Pat Lilley

- Reducing the stock items – Need to look at the whole picture

- DIAGNOSTIC IMAGES

- Mountain behind a mountain

- The Disappearing Act

- EDITORIAL

- EDITORIAL BOARD

- TO CRUSH OR NOT TO CRUSH? DON’T RUSH TO CRUSH!

- Effectiveness of Pre – Clinical Competency Certification Program on Improving Knowledge of Clinical Practice Among Nursing Internship Students

- Medical Statistics in Clinical Research – Mean, Median, Standard Deviation, p-value, Chi Squared test

- Vertebral artery dissection with thrombosis causing neuralgic amyotrophy

- Atypical Electrical Alternans Due to Large Left Pleural Effusion

- Early presentation of a rare disorder

- DIAGNOSTIC IMAGES

- PATIENT’S STORY

- ANTHOLOGY OF POEMS

- EDITORIAL

- EDITORIAL BOARD

- GUEST EDITORIAL

- Clinical MIS – A Clinical Analyst Review

- Eclampsia and HELLP Syndrome: A Case Report

- Percutaneous Device Closure in A Toddler with PDA and Interrupted IVC

- Pediatric Car Passenger Trauma – A Case Report and A Review of Child Safety Inside a Car

- Use Of Antibody Cocktail, Regn-Cov2, In Two Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL) Patients with Mild Covid-19 Disease, At A Tertiary Care Hospital in South India: A Case Series

- Neurology Update

- DIAGNOSTIC IMAGES

- The Patient Is Always Right

- Humanity’s Most Cherished Fiction

- DVT in a child: A case to introspect

- Rainbow within a storm

- Reversal of Dabigatran in patients with intracerebral haemorrhage – a narrative review

- EDITORIAL

- EDITORIAL BOARD

- GUEST EDITORIAL

- Convalescent Plasma Therapy in Covid-19: A Question of Timing

- High Dose methotrexate in Children with Cancer Without Drug Level Monitoring – 133 Cycles Experience

- Prenatal diagnosis in Thalassemia – Prevention is better than cure

- Improving Outcomes in Children with Cancer – Our Experience

- Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation for Myeloma with CKD

- All Megakaryocytic Macrothrombocytopenia Are Not ITP

- Telomeropathies and Our Experience: A Case Series

- Neurology Update – Neurobiology of Sleep

- Journal scan: A review of twelve recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

- The Brush Stroke

- A rare case of flood syndrome: a case report of fatal complication of umbilical hernia in liver cirrhosis

- Editorial

- Kauverian eMedical Journal

- COVID-19 and the Change in Perspective: Musings of Two Seasoned Pediatricians

- World Prematurity Day: Reflections of a Neonatologist

- Epilepsy in Kids: Problems Beyond Seizures

- Overcoming Challenges and Performing First Paediatric Allogenic Bone Marrow Transplantation in Trichy

- Vaccine Induced Cerebro Venous Thrombosis with Thrombocytopenia (VITT) – A Case Report

- DX ICD Implanted After Unmasking Brugada – A Case Study

- DNB Thesis

- Kauvery 4th Annual Nursing Conclave N4 – 2021

- Learning from Experience – 13 and 14

- The Consultation Room

- Journal Scan

- Recommended Reading

- Diagnostic Image

- From Sand to Sky

- Editorial

- Kauverian eMedical Journal

- Transfusion-related acute lung injury

- Equalizing leg length by “lengthening the shorter leg” by surgery: a case report

- VKA induced catastrophic bleeding management with Prothrombin Complex Concentrate (PCC): a practice changer

- “Kanvali Kizhangu” Toxicity – A Curious Case Report

- Orthopaedics case series

- Morbidity and mortality meetings for improved patient care

- Significance of waist to height ratio as an early predictor in developing metabolic syndrome in children of age group 5-12 years in a tertiary care centre in Trichy: Part IV

- Chapter 15

- The Consultation Room

- Journal scan: A review of 10 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

- Recommended Reading

- Measuring Association in Case-Control Studies

- DIAGNOSTIC IMAGE

- The Stream of Life

- Kauverian eMedical Journal

- Let’s prepare for the unexpected guest who always arrives at odd hours: Pre-eclampsia

- Cerebrospinal fluid-cutaneous fistula after neuraxial procedure and management: a case report

- Impella CP assisted recovery of acute COVID 19 fulminant myocarditis presenting as out of hospital cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock

- Ischemic stroke after Russel’s Viper snake bite, an infrequent event: a case report

- Nutrition needs of preterm babies

- Chapter 17

- The Consultation Room

- Journal scan: A review of 10 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

- DIAGNOSTIC IMAGE

- Tick Talk

- EDITORIAL

- EDITORIAL BOARD

- Cervical collar in trauma patients – friend or foe?

- Oxygen conservation strategies

- Chronic periodontitis: a case report

- Erythema multiforme in COVID-19: a case report

- Secondary Synovial Chondromatosis of the knee Joint-a case report

- Statistical Risk Ratio (Relative Risk) Data Analysis

- Journal scan: A review of ten recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

- Splinter Haemorrhage

- Dignity matters

- Where does time fly to?

- DIAGNOSTIC IMAGE 1

- Editorial

- Editorial Board

- ABO incompatible renal transplant in a post COVID patient with COVID antibodies

- Neuromyelitis Optica early presentation of an adult disorder

- The gamut of neurological disorders associated with COVID-19

- Anaesthetic management of patients with Takayasu arteritis

- My Pains and Gains in Becoming A Doctor

- Significance testing of correlation coefficient

- Journal scan: A review of ten recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

- While you were sleeping

- Subliminal Sublimes (Sonnet 1)

- Editorial

- Instructions for Authors

- COVID-19 and mucormycosis: the dual threat

- COVID-19 associated mucormycosis: efforts and challenges

- Saccular abdominal aortic aneurysms: a case series

- Trauma and OCD – A Case of a Boy with Dark Fears

- Chapter 3

- Journal scan: A review of 10 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

- The Consultation Room

- DIAGNOSTIC IMAGE

- A Patient’s Perception of Pulmonology

- Just a leaf

- Editorial

- Editorial Board

- Dilemma of shadows

- One-year journey in Kauvery! Challenges in Neuroanaesthesia and Neurointensive care

- Leadless pacemakers: The future of pacing?

- Clinical Therapeutics: The polymyxins, existing challenges and new opportunities

- Decision to Take Up a Patient in The Presence of Arrhythmias

- Why growing public dissatisfaction about medical profession?

- JOURNAL SCAN

- Diagnostic Image

- The cloud over a young life

- The Waiting Room

- Author Instruction

- Editorial

- Editorial Board

- The French Connection!

- Rare cause of pyrexia of unknown origin: Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Impact of multi-disciplinary tumour board (MDT) on cancer care

- WPW pathway ablated from uncommon location

- Statistical hypothesis – using the t-test

- Learning from Experience – Chapters 6 and 7

- The Consultation Room

- Journal scan: A review of 10 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

- Diagnostic Image

- When the sun sets over a good life

- The Deepening Dent

- Save Farmers, Save Future

- Editorial

- Editorial Board

- Guest Editorial

- Significance of waist to height ratio as an early predictor in developing metabolic syndrome in children of age group 5-12 years in a tertiary care centre in Trichy: Part I

- Journal Club

- Statistical Non Parametric Mann – Whitney U test

- The Consultation Room

- Journal scan: A review of 10 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

- Diagnostic Image

- Editorial

- Editorial Board

- Repurposing anti-rheumatic drugs in COVID

- An Effective Journal Club Presentation: A Guide

- A Masquerader Vasculitis as Usual: Time Is Tissue

- A Sinister Swelling: A Case Report

- DNB Thesis

- Statistical Regression Analysis

- Learning from Experience – 11 and 12

- The Consultation Room

- Journal Scan

- Diagnostic Image

- Stained not torn

- Editorial

- Author Instruction

- Interventional Nephrology

- Amplified Ears and Listening Brains

- Love makes life worth living

- Usage of Dapagliflozin in Elderly

- Severe Methemoglobinemia Treated Successfully with Oral Ascorbic Acid: A Case Report

- The new imitator

- Liver Cyst

- Learning from Experience – Intra Operative, Chapters 17 and 18

- The Consultation Room

- Journal scan

- Recommended Readings

- Editorial

- Evolution of Emergency Medicine in India and the Emergence of the MEM Program at Trichy

- Welcome to the Dance floor: The Emergency Room

- Life of An Emergency Physician

- A Racing Heart Beat: To Shock or Not

- Being Calm Amidst Chaos: Tips on How to Be an Expert Emergency Nurse

- COVID COVID everywhere, but not a place to run away from!

- Proud to be an Emergency Nurse: Life in the fast lane!!!

- The Journey of a Fresher Nurse in the ED

- Ready, Steady, Go!!! A brief on Green Corridor activation in Organ Transplantation

- An Elevator Story!!!

- Veno-occlusive mesenteric ischemia: A case report

- Stridor: An Alarming Sign in Emergency

- Amnesia in the ER: That Ghajini Moment!!! A Case series

- Survival After Paraquat Ingestion: A Case Series

- When you save one life, you save a family

- Severe Methemoglobinemia, Unresponsive to Methylene Blue

- Severe Meliodosis With Multisystemic Involvement: A Case Report

- A Case Report

- Recognize Rhabdomyolysis early to prevent Acute Kidney Injury and Acute Renal Failure

- New Onset Refractory Status Epilepticus (NORSE)

- Sensitive of EFAST in trauma in correlation with CT scan

- Sub Arachnoid Haemorrhage, management in Emergency and Neuro Intensive care

- Uncommon presentation of Takayasu Arteritis as a convulsive syncope

- All right sided hearts are not Dextrocardia

- COVID and the Salt Story

- Acute Lower Limb Ischemia: A Clue to Underlying Aortic Dissection

- Globe Injury with Orbital Blow Out Fracture

- The heat-stricken life – Treatment in time only saves lives!

- Pneumoperitoneum, does it have any clinical significance?

- Hypertensive Emergency in the ED

- Role of a paramedic in inter-hospital transfer

- Golden Hours in Safer Hands

- Through rough, crowded roads and stagnant waters – we race against time to reach you!

- Editorial

- Author Instruction

- Nana M, et al. Diagnosis and Management of COVID-19 in Pregnancy. BMJ 2022;377:e069739.

- MICS CABG with LIMA and Left Radial artery, harvested by Endoscopic technique: An ultrashort report

- Ultra-Short Case Report

- An interesting case of Bilateral Carotid aneurysms

- A Case Report

- Uterine artery embolization: Saving a mother and her motherhood

- Acute Abdomen – Sepsis – CIRCI: A Success Story

- Diagnostic Image

- Learning from Experience – Intra Operative, Chapters 19 and 20

- The Consultation Room

- Journal Scan

- Recommended Readings

- Editorial

- Kauverian eMedical Journal

- Cardiothoracic surgery in the COVID era: Revisiting the surgical algorithm

- Review

- Corona warrior award

- Case Series

- Takotsubo cardiomyopathy

- Learning from Experience – Chapters 3 and 4

- The Consultation Room – Chapters 41 to 45

- Journal scan

- Recommended Reading

- DIAGNOSTIC IMAGE

- Poem from Staff Nurse

- Editorial

- Author Instruction

- Male V. Menstruation and COVID-19 vaccination

- Efficacy and doses of Ulinastatin in treatment of Covid-19 a single centre study

- Electronic registries in health care

- A case report

- Anaemia in pneumonia: A case report

- Successful treatment of two cases of rare Movement Disorders

- Analysis of variance Two-Way ANOVA

- Learning from Experience – Chapters 5 and 6

- The Consultation Room

- Journal Scan

- Recommended Reading

- Diagnostic Image

- Poem from Staff Nurse

- Editorial

- Kauverian eMedical Journal

- An obituary, farewell to a very dear friend

- ‘Vitamin D’: One vitamin, many claims!

- Implantation of Leadless Pacemaker in a middle-aged patient: An ultra-short case study

- ABO-incompatible renal transplant at ease

- Basal cell adenoma parotid: A case report

- A case report

- Learning from Experience – Chapters 7 and 8

- The Consultation Room

- Journal Scan

- Recommended Reading

- Diagnostic Video

- Poem from Staff Nurse

- Editorial

- March – the Month for Minds to dwell on Multiple Myeloma

- Covid Report

- Research Protocol

- New Arrows in our Quiver, to direct against SARS-CoV-2 variants

- Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

- Last on the list: A diagnosis seldom considered in males

- Giant T wave inversion associated with Stokes: Adams syndrome

- Learning from Experience – Intra Operative, Chapters 9 and 10

- The Consultation Room

- Definitions of probability

- Journal Scan

- Recommended Reading

- Diagnostic Video

- A Thanksgiving to Cardiac Surgeons

- Editorial

- Kauverian eMedical Journal

- Research Article

- Research Protocol

- Saving the unsavable

- Case Report

- Case Report

- Letters to the Editor

- Diagnostic Image

- Learning from Experience – Intra Operative, Chapters 13 and 14

- The Consultation Room

- Journal Scan

- Recommended Readings

- Editorial

- Author Instruction

- SIGARAM – The Club for Children with Diabetes

- The hope for a better tomorrow

- An unusual complication of polytrauma:

- An enigma at the ER

- Dynamic examination of airway

- Journal Club

- Journal Club

- Journal Club

- Conditional Probability

- Diagnostic Image

- Learning from Experience – Intra Operative, Chapters 15 and 16

- The Consultation Room

- Journal Scan

- Recommended Readings

- EDITORIAL

- Kauverian eMedical Journal

- Junior nurses in Kauvery Hospital on the frontline against the COVID-19 pandemic

- Emergency Medicine, the Emerging Specialty: Leading Light on the entrance to the Health Care Pathway

- Battle of two drugs: Who won? – An unusual presentation

- Return of the native and a resurrected foe: A case of Rhinocerebral Mucormycosis

- Covert invader- atypical presentation of neuronal migration disorder

- Fragile heart: an unusual cause of chest pain

- Goldberger’s ECG sign in Left Ventricular Aneurysm

- The Power of Purple

- Beads of Nature’s Rattle

- Case Report

- EDITORIAL

- Kauverian eMedical Journal

- Modification of Management Strategies, And Innovations, During SARS Cov2 Pandemic Improved the Quality, Criticality and Outcomes in In-Patients “Rising to the occasion”, the mantra for success in the COVID -19 pandemic

- Time in Range (TIR) In Diabetes: A Concept of Control of Glycemia, Whose Time Has Come

- Kauvery Heart Failure Registry- A Concept

- Shorter Course of Remdesivir In Moderate Covid-19 is as Efficacious as Compared to Standard Regime: An Observational Study

- CASE REPORT

- Lymphoepithelial Carcinoma: A Case Report of a Rare Tumour of The Vocal Cord

- Diabetic Keto Acidosis (DKA), Associated with Failed Thrombolysis with Streptokinase in Acute Myocardial Infarction

- EARNING FROM EXPERIENCE – CHAPTERS 1 AND 2

- The Consultation Room

- Journal scan

- Recommended Reading

- DIAGNOSTIC IMAGE

- Notes to Nocturne

- Editorial

- Kauverian eMedical Journal

- Caring for nobody’s baby

- Special Report

- Research Article

- The curious case of a migrating needle on the chest wall

- Foreign body: A boon at times

- Cardiorenal Syndrome

- What My Grandmother Knew About Dying

- Endovascular Therapy for Acute Stroke with a Large Ischemic Region. N Engl J Med. 2022

- Letter to the Editor

- Clinical outcomes of Coronary Artery Disease in Octogenarians

- Diagnostic Image

- Learning from Experience – Intra Operative, Chapters 11 and 12

- The Consultation Room

- Journal Scan

- Recommended Reading

- colours

- Editorial

- Author Instruction

- Ultrashort Case Report

- Cochlear Implantation: Expanding candidacy and Cost Effectiveness

- Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum in COVID 19 – Tertiary Care Centre Experience in South India

- Amoxycillin Induced Anaphylactic Shock: A Case Report

- An Unusual Cause of Seizures: A Case Report

- Case Report

- Educational Strategies to Promote Clinical Diagnostic Reasoning

- Rheumatic Rarities

- Types of sampling methods in statistics

- Diagnostic Image

- Learning from Experience – Intra Operative, Chapters 21 and 22

- The Consultation Room

- Journal Scan

- Recommended Readings

- Editorial

- Author Instruction

- Journal Scan

- Myeloma

- Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES)

- Prophylactic orthopaedic surgery

- Subclavian steal: An interesting imaging scenario

- Spondylo-epi-metaphyseal dysplasia (SEMD)

- The bleeding windpipe

- Learning from Experience – Intra Operative, Chapters 23 and 24

- The Consultation Room

- Diagnostic Image

- Recommended Readings

- Editorial

- Editorial Board

- Physician, Protect thyself

- Foetal Medicine, the Future is here!

- Japanese Encephalitis: A common menace

- Carpometacarpal dislocation with impending compartment syndrome

- Heterotopic pregnancy

- Femoral Trochantric and Proximal Humerus Fracture, from Diagnosis to Rehabilitation

- My Father’s Heart Block

- EPS page

- CRT CSP Cases

- Journal scan

- Learning from Experience – Intra Operative, Chapters 25 and 26

- The Consultation Room

- Recommended Readings

- Editorial

- Editorial Board

- Multiple Sclerosis: An overview

- A flower born to blush unseen

- Guest Editorial

- Radio-frequency ablation as an effective treatment strategy in a case of VT storm post STEMI

- Lymphatic malformation of tongue

- Bilateral anterior shoulder dislocation in epilepsy: A case report and review of literature

- An unusual cause of Stridor

- Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) – the magic bullets: A review of therapeutic applications and its future perspectives

- Write the Talk

- Press release and Comments

- Probability Distribution of Bernoulli Trials

- Journal Scan

- Recommended Readings

- poem-v4i4

- Editorial

- Editorial Board

- Research

- Research

- Lambda-cyhalothrin and pyrethrin poisoning: A case report

- Good Enough

- The Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): the beginning

- Comprehensive trauma course 2022: Trauma Management & Kauvery

- Comprehensive trauma course 2022: Introduction to Comprehensive trauma course

- Diagnostic Image

- Learning from Experience – Intra Operative, Chapters 27 and 28

- The Consultation Room

- Recommended Readings

- Poem

- Editorial

- The Brave New World of Anaesthesia

- Anesthetic considerations in Wilson’s disease for fess: A case report

- The painful story behind modern anaesthesia

- Anesthesia considerations for Ankyslosing Spondylitis

- Total intravenous anaesthesia: An overview

- Risk stratification for cardiac patients coming for non-cardiac surgeries

- The Anaesthesiologist’s role in fluoroscopic guided epidural steroid injections for low back pain

- Awake Craniotomy

- Malpositioned central venous catheter: Step wise approach to avoid, identify and manage

- Benefits outweighing risk: Neuraxial anaesthesia in a patient with Spina Bifida with operated Meningomyelocele

- Pain free CABG: newer horizon of minimally invasive cardiothoracic surgery a walk through anaesthesiologist perspective

- Stellate Ganglion Block: A bridge to cervical sympathectomy in refractory Long QT Syndrome

- Venous Malformation in Upper Airway – Anesthetic Challenges and Management: A Case Report

- Editorial

- USG guided peripheral nerve block in surgery for hernia

- Anaesthesia and morbid obesity: A systematic review

- Patient-Controlled Analgesia

- Parapharyngeal abscess of face and neck: Anesthetic management

- 3D TEE, a boon for the diagnosis of Left Atrial Appendage thrombus!

- Anaesthetic management of difficult airway due to retropharyngeal abscess and cervical spondylosis

- Expect the unexpected – Breach in continuous nerve block catheter

- Lignocaine nasal spray: An easy remedy for Post Dural Puncture Headache

- Potassium permanganate poisoning and airway oedema

- Angioedema following anti-snake venom administration

- Editorial

- Editorial Board

- Ra Fx ablation of Atrioventricular nodal reciprocating tachycardia

- Pace and Ablate Strategy: Conduction system pacing with AV junction ablation for drug refractory atrial arrhythmia – A novel approach

- Why Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (CRT) For complete heart block? A case discussion

- Pacemakers and Bradyarrhythmias in Diabetic Mellitus

- Outcomes of Total Knee Arthroplasty in patients aged 70 years and above

- An approach to CBC for practitioners

- Acute cerebral sinus venous thrombosis with different presentations and different outcomes: A case series

- Diet and nutritional care for DDLT: A case study

- Vaccine for Dengue (Dengvaxia CYD-TDV)

- Diagnostic Image

- Learning from Experience – Intra Operative, Chapters 31 and 32

- Recommended Readings

- காவிரித்தாய்

- ATLAS OF HAEMATOLOGY AND HEMATOONCOLOGY

- Editorial

- Editorial Board

- Case reports and Case series:

- Usefulness of NEWS 2 score in monitoring patients with cytokine storm of COVID-19 pneumonia

- Treatment approach for extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis (XDR-TB)

- Modified Lichtenstein mesh repair, for a patient of Coronary Artery Disease, Heart Failure and with Implanted Cardioverter- Defibrillator

- Fever-induced Brugada Syndrome

- Pulmonary Thrombo Embolism: When to Thrombolyse?

- Ultra-Short Case Report

- Learning from the failure of Nebacumab

- Journal scan

- Learning From Experience Intra Operative Chapters 29 and 30

- Recommended Readings

- Poem

- Editorial

- Editorial Board

- Heart transplantation: Life beyond the end of life

- Azithromycin to Prevent Sepsis or Death in Women Planning a Vaginal

- Medial retropharyngeal nodal region sparing radiotherapy versus standard radiotherapy

- Proximie: Patient safety in surgery – the urgent need for reform

- Analysis of femoral neck fracture in octogenarians and its management

- Adult Immunisation in Clinical Practice: A Neglected Life Saver

- “Icing” The Eyes

- Doppler vascular mapping in Arterio Venous Fistula (AVF)

- Cosmesis and cure: Radiotherapy in basal cell carcinoma of the dorsum of nose – A case report

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Portal Hypertension

- Comprehensive review of Drug-Induced Cardiotoxicity

- Statistics – Data Collection – Case Study Method

- Atlas of Haematology and Hematooncology

- PRE-OPERATIVE Chapters 1 and 2 – Learning from Experience

- Chapter 2. Uncertainties in medicine in spite of advances

- No Splendid Child

- Editorial

- Editorial Board

- A Young Girl Lost in the Storm

- ECMO as a bridge to Transplant: A case report

- Renal anemia – from bench to bedside

- Mission Possible

- New kids on the block – Update on diabetic nephropathy therapy

- Infections – Trade off in Transplants

- To Give Or Not to Give – Primer on Bicarbonate Therapy

- Sialendoscopy: Shifting paradigms in treatment of salivary gland disease

- Gait imbalance in a senior due to Chronic Immune Sensory Polyneuropathy (CISP)

- Statistics – Mcnemar Test

- Atlas Of Haematology And Hematooncology

- PRE-OPERATIVE Chapters 3 and 4 – Learning from Experience

- Changing trends a challenge to the already trained

- Journal scan

- Recommended Readings

- EDITORIAL

- EDITORIAL BOARD

- PREGNANCY POST-RENAL TRANSPLANT

- BALLOON-OCCLUDED RETROGRADE TRANSVENOUS OBLITERATION

- REVERSE SHOULDER ARTHROPLASTY FOR ROTATOR CUFF ARTHROPATHY

- THE AMBUSH A TEAM APPROACH

- ENDOSCOPIC TRANS-SPHENOID APPROACH FOR PITUITARY ADENOMA EXCISION

- A STUDY ON PRESENTATION AND OUTCOME OF BULL GORE INJURIES IN A GROUP OF TERTIARY CARE HOSPITALS

- A CASE OF INTERNUCLEAR OPHTHALMOPARESIS AS THE FIRST MANIFESTATION OF MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

- GRANULOMATOSIS WITH POLYANGITIS AND LUNG INVOLVMENT (WEGENER’S DISEASE)

- RITUXIMAB (RITUXAN, MABTHERA) IN THE TREATMENT OF B-CELL NON-HODGKIN’S LYMPHOMA

- STATISTICAL SIGNIFICANCE

- Atlas Of Haematology And Hematooncology

- PRE-OPERATIVE CHAPTERS 5 AND 6 – LEARNING FROM EXPERIENCE

- Chapter 4: Diagnostic process often reversed

- Journal scan: A review of 25 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

- Recommended Readings

- ஆரோக்கியம் நம் கையில்

- வெற்றியின் பாதை

- Editorial

- Editorial Board

- Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in a multi-speciality hospital orthopaedic outpatient clinic

- Esomeprazole induced Hypoglycemia

- Dynamic external fixator for unstable intra articular fractures of Proximal Interphalangeal Joint (PIP): “Suzuki” frame

- How to Practice Academic Medicine and Publish from Developing Countries? A Practical Guide, Springer Nature, 2022

- WINTNCON 2022 – Scientific Program

- Pulmonary Thrombo Embolism: A state of the art review

- Role of Artificial Intelligence in improving EHR/EMR and Medical Coding and billing

- Monoclonal Antibodies: Edrecolomab and Abciximab

- Atlas of haematology and hematooncology

- Journal scan

- Learning from Experience – Intra Operative, Chapters 31 and 32

- What doctors must learn: Doctor, look beyond science

- Recommended Readings

- I Whisper Secrets In My Ear

- EDITORIAL

- Instructions for Authors

- Mismatched Haploidentical Bone Marrow Transplantation in a 10-year-old boy with relapsed refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia, at Trichy

- ST-Segment Elevation is not always Myocardial Infarction

- Acyanotic Congenital Heart Disease, repaired, evolves into a Cyanotic Congenital Heart Disease and presents with an atrial tachycardia

- Family medicine – caring for you for the whole of your life. A Lost and Found Art

- The Principles and Practice of Family Medicine

- Complete Heart Block

- Sick Sinus Syndrome (SSS)

- The First Ever National Award Comes to Kauvery Hospital Chennai & Heart City for Safety and Workforce Category in IMC RBNQA Milestone Merits Recognition 2022

- Diagnostic Image

- PRE-OPERATIVE CHAPTERS 7 AND 7 – LEARNING FROM EXPERIENCE

- Chapter 5: Super-specialist – boon or bane

- Journal scan: A review of 42 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

- RECOMMENDED READINGS

- நேரம் ஒதுக்கு

- மருத்துவரின் மகத்துவம்

- EDITORIAL

- Instructions for Authors

- Surgical Management of Covid-19 Associated Rhino-Orbito-Cerebral-Mucormycosis (Ca-Rocm) – A Single Centre Experience

- Knee Joint Preservation Surgeries

- Guest Editorial Comments

- Ventricular Septal (VSR) closure with ASD device

- Newer Calcium Debulking Angioplasty technique of Orbital Atherectomy

- An hour-long CPR to restart the heart

- VT or SVT with aberrancy?

- Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumor (PitNET)

- VSD Device Closure

- PDA Device Closure

- Iron Deficiency Anemia, Post MVR

- Torsades de Pointes

- Quality improvement project to Reducing the Malnutrition Rate of ICU patients from 43% to 20%

- Long term use of Amiodarone in Cardiac patients: A Clinical Audit

- Statistical Independent Events and Probability

- PERI-OPERATIVE Chapters 9 and 10 – Learning from Experience

- Journal scan: A review of 40 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

- EDITORIAL

- Kauverian Medical Journal

- First da Vinci Robotic Surgery in Carcinoma Prostate: A Case Report

- Black burden or Taylor the saviour: A case report

- Analysis of differences in Oncology practice between the United Kingdom and India

- A Case of Takayasu Arteritis

- Idiopathic Dilated Pulmonary Artery (IDPA)

- ECG Atlas

- Unusual cause of Dysphagia: A case report

- Tu Youyou: The scientist who discovered artemisinin

- Continuing Nursing Education (CNE) on Risk assessment tools, to assess vulnerable patients at Kauvery Hospital, Tennur

- DIAGNOSTIC IMAGE

- PRE-OPERATIVE CHAPTERS 11 AND 12 – LEARNING FROM EXPERIENCE

- OLD AND NEW – MAKE THE BEST OF THE TWO

- Journal scan: A review of 30 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

- Recommended Readings

- EDITORIAL

- INSTRUCTION TO AUTHORS

- A pregnant patient with DKA, septic shock and a lactate mystery

- Radical Thymectomy in Myasthenia Gravis through Partial Sternotomy approach: A report on three patients

- In-utero blood transfusion in two etiologically distinct anaemic fetus

- RARE CAUSE OF PULMONARY HYPERTENSION

- Acute Rheumatic fever is still an enigma

- A remarkable journey: Managing LQTS in a 43-year-old female with recurrent syncope and seizure

- An unusual case of Acute Coronary Syndrome

- Reversible cause of severe LV Dysfunction in Left Bundle Branch Block

- A case study on Rhino-Orbital-Cerebro- Mucormycosis

- Snakebite and its management

- Total Elbow arthroplasty in Post Traumatic arthritis

- Wellens Syndrome: An ECG finding not to miss!

- Dr. C.R. Rao Wins Top Statistics Award a look back at his pioneering work

- PRE-OPERATIVE Chapters 13 and 14 – Learning from Experience

- Chapter 7. Doctor-patient relationship

- Journal scan: A review of 30 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

- EDITORIAL

- INSTRUCTION TO AUTHORS

- FROZEN ELEPHANT TRUNK (FET) PROCEDURE IN A 52 YEARS OLD CHRONIC AORTIC DISSECTION PATIENT

- DIAGNOSING AND MANAGING EISENMENGER SYNDROME IN A YOUNG MALE

- STEMI EQUIVALENT BUT STEMI!

- TEMPORARY HEAL CAN POSSIBLY KILL!

- UNDERSTANDING PUBERTY

- THE IMPORTANCE OF STATISTICS IN HEALTHCARE

- JOURNAL SCAN: A REVIEW OF 44 RECENT PAPERS OF IMMEDIATE CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE, HARVESTED FROM MAJOR INTERNATIONAL JOURNALS

- DIAGNOSTIC IMAGE

- PRE-OPERATIVE CHAPTERS 15 AND 16 – LEARNING FROM EXPERIENCE

- CHAPTER 8. DOCTOR-DOCTOR RELATIONSHIP

- EDITORIAL

- GUEST EDITORIAL

- CLINICAL AUDIT: AN INTRODUCTION

- YOUNG ACS AUDIT

- CLINICAL AUDIT: ANAESTHESIA

- CLINICAL OUTCOME IN ICU PATIENTS

- RATE OF MALIGNANCY IN INDETERMINATE OVARIAN CYST – A PROCESS AUDIT

- PATTERNS OF NEEDLE DISPOSAL AMONG INSULIN USING PATIENTS WITH DIABETES MELLITUS: AN AUDIT

- CONTINUOUS PATIENT MONITORING – LIFE SIGNS

- AGE IS JUST A NUMBER!

- SVT WITH LEFT BUNDLE BRANCH BLOCK FOLLOWING GASTRECTOMY

- COMPLEX AORTIC DISSECTION WITH MULTIFACETED CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS

- EDITORIAL

- POST-OPERATIVE SORE THROAT IN GA: A CONCERN

- NEONATAL HLH: OUR EXPERIENCE

- CLINICAL REVIEW MEET 16TH NOV 2023: CHALLENGES IN SETTING UP A NEW HSCT CENTRE IN A TIER-2 CITY IN INDIA

- CARDIAC BIOMARKERS: CLINICAL UTILITY

- HIRAYAMA DISEASE: A CLINICAL-RADIOLOGICAL REVIEW

- ECG AS A WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY: FOR HYPERKALEMIA

- EFFECTIVENESS OF ROOD’S APPROACH BASED PAEDIATRIC OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY MANAGEMENT: ON CHILDREN WITH CONGENITAL MUSCULAR TORTICOLLIS

- ELTROMBOPAG, A NOVEL THROMBOPOIETIN (TPO) RECEPTOR AGONIST: AN OVERVIEW

- HENOCH-SCHONLEIN PURPURA

- SUBMANDIBULAR GLAND SIALADENITIS SECONDARY TO SUBMANDIBULAR CALCULUS

- LEAN HOSPITALS

- STATISTICS BLACK-SCHOLES MODEL

- PERI-OPERATIVE CHAPTERS 17 AND 18 – LEARNING FROM EXPERIENCE

- CHAPTER 9. BUILDING BLOCKS OF PATIENT CARE

- JOURNAL SCAN: A REVIEW OF 30 RECENT PAPERS OF IMMEDIATE CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE, HARVESTED FROM MAJOR INTERNATIONAL JOURNALS

- EDITORIAL

- INSTRUCTIONS TO AUTHORS

- ROTATHON-SERIES OF SUCCESSFUL ROTA CASES LAST 2 MONTHS: AN AUDIT

- OUTCOMES OF AKI AUDIT IN KAUVERY

- ETIOLOGY, CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS AND OUTCOMES OF PATIENTS WITH ACUTE PANCREATITIS IN KAUVERY CANTONMENT HOSPITAL (KCN), TRICHY

- USE OF BLOOD PRODUCTS AND STEROIDS IN THE MANAGEMENT OF DENGUE AT KAUVERY TRICHY HOSPITALS: A CLINICAL AUDIT

- A CLINICAL AUDIT: ON THE MANAGEMENT OF ECTOPIC PREGNANCY

- DIABETIC KETOACIDOSIS WITH HIGH ANION GAP METABOLIC ACIDOSIS

- HYPOKALEMIC PARALYSIS FROM DISTAL RENAL TUBULAR ACIDOSIS (TYPE-1)

- DELAYED PRESENTATION OF INTERMEDIATE SYNDROME IN A PATIENT WITH ORGANOPHOSPHORUS POISONING: A CASE REPORT

- SCAPULA FRACTURES: DO WE NEED TO FIX THEM?

- SPONTANEOUS CSF RHINORRHEA

- DANCING WITH DIABETES: AN UNUSUAL CASE OF CHOREA HYPERGLYCEMIA BASAL GANGLIA SYNDROME

- CONVALESCENT RASH OF DENGUE

- ECG ATLAS 2

- MI MIMICKER

- PERFORATION PERITONITIS-A CASE REPORT

- APPLICATION OF EVIDENCE BASED PRACTICE CARE FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH SPINAL CORD INJURY WITH FUNCTIONAL DIFFICULTIES: ROLE OF THE OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY PRACTICE GUIDELINES

- METHOTREXATE INDUCED MUCOSITIS AND PANCYTOPENIA: A CONSEQUENCE OF MEDICATION ERROR IN A PSORIASIS PATIENT

- POST OPERATIVE CHAPTERS 1 AND 2 – LEARNING FROM EXPERIENCE

- CHAPTER 10. NURTURING SELF

- விடாமுயற்சி வெற்றி தரும்

- JOURNAL SCAN: A REVIEW OF 26 RECENT PAPERS OF IMMEDIATE CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE, HARVESTED FROM MAJOR INTERNATIONAL JOURNALS

- EDITORIAL

- EDITORIAL BOARD

- LIMB SALVAGE IN EXTREMITY VASCULAR TRAUMA: OUR EXPERIENCE

- MANAGEMENT OF URETHRAL CATHETER RELATED PAIN IN RENAL TRANSPLANT RECIPIENTS: A CLINICAL AUDIT

- NO PAIN VEIN GAIN WITH PRILOX IN PAEDIATRIC POPULATION

- GUIDELINE-DIRECTED MEDICAL TREATMENT (GDMT) OF HEART FAILURE AT KAUVERY HOSPITALS: A CLINICAL AUDIT

- PATIENTS STORY: DIGNITY MATTERS

- PATIENTS STORY: DIGNITY MATTERS

- VIDEO PRESENTATION- CT CORONARY ANGIOGRAPHY

- DRUG INDUCED HYPERKALEMIA

- ADULT NEPHROTIC SYNDROME

- EXPLORING COMPLEX CARDIAC CASES: INSIGHTS FROM DIVERSE PRESENTATIONS IN MID-AGED WOMEN

- EFFECTIVENESS OF ACTIVITY CONFIGURATION APPROACH BASED OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY INTERVENTION FOR CHILDREN WITH CONGENITAL MUSCULAR TORTICOLLIS: A CASE STUDY

- CARDIOMYOPATHY AND ITS ECHO FINDINGS

- THE STRESS TEST ON THE TREADMILL

- POST OPERATIVE CHAPTERS 3 AND 4 – LEARNING FROM EXPERIENCE

- CHAPTER 11. BALANCE IN LIFE BEYOND BANK BALANCES

- JOURNAL SCAN: A REVIEW OF 30 RECENT PAPERS OF IMMEDIATE CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE, HARVESTED FROM MAJOR INTERNATIONAL JOURNALS

- காணும் பொங்கலும் மனித மன மாற்றமும்

- EDITORIAL

- INSTRUCTIONS TO AUTHORS

- PREVALENCE OF STREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIAE SEROTYPES IN AND AROUND TRICHY AND ITS CLINICAL RELEVANCE

- ANAESTHETIC MANAGEMENT OF A PATIENT WITH HUGE GOITER: A CASE REPORT

- EUGLYCEMIC DIABETIC KETOACIDOSIS A RARE CAUSE FOR DELAYED EXTUBATION

- SUCCESSFUL PREGNANCY IN ASD PATIENT – COMPLICATED BY SEVERE PULMONARY ARTERIAL HYPERTENSION

- ENDOCRINE COMPLICATION OF GROWTH HORMONE SECRETING TUMOR: A CASE REPORT

- EFFICACY OF EARLY DIAGNOSIS AND DEVELOPMENT APPROACHES OF PAEDIATRIC OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY ON ACUTE DISSEMINATED ENCEPHALOMYELITIS: A CASE REPORT

- POST OPERATIVE CHAPTERS 5 AND 6 – LEARNING FROM EXPERIENCE

- CHAPTER 12. MILES TO GO – BEFORE TEACHING BECOMES LEARNING

- JOURNAL SCAN: A REVIEW OF 26 RECENT PAPERS OF IMMEDIATE CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE, HARVESTED FROM MAJOR INTERNATIONAL JOURNALS

- காவேரி – 25

- POEM – மண்ணில் பிறந்தது சாதிப்பதற்குத்தான்