Anaphylaxis to Antibiotic

Dr. Vasanthi Vidyasagaran*

Department of Anaesthesiology, Kauvery Hospital, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India

*Correspondence: Vasanthi.vidyasagaran@gmail.com

Chapter 3

A 36-year-old primigravida was admitted for an elective LSCS. She had conceived following infertility treatment. Her investigations and clinical examination were within normal limits. Surgery was planned under spinal anesthesia.

As the anesthetist was preparing to administer the spinal, a nurse injected Cefazolin 2 g IV under the supervision of the obstetrician. Soon after, the patient complained of an unexplained peculiar sensation in the throat and had nausea. This reaction to Cefazolin is not uncommon and patients usually recover without any further side effects. But, this patient developed severe oedema of her lips, neck, and hands, within seconds. She had difficulty in even talking due to progressive oedema of her tongue.

Patient was fully conscious and very apprehensive. Due to the rapidly increasing oedema, her pulse could not be felt and blood pressure could not be measured. ECG showed sinus tachycardia of 130/min. Oxygen was administered through the face mask. Hydrocortisone 200 mg and Chlorpheniramine 10 mg was given intravenously.

Suspecting severe allergic reaction, probably anaphylaxis to antibiotic administered, injection Adrenaline 100 mcg was given intravenously and rest 900 mcg into 50 ml normal saline infusion. There was no improvement in her condition; meanwhile the foetal heart rate was beginning to drop, and caesarean section had to be performed immediately. It was quite a challenge to even decide the type of anesthesia to be administered. Regional anaesthesia, in the form of spinal or epidural was not considered at this point, as the patient and the unborn foetus were deteriorating rapidly. Airway and oxygenation were priority.

Difficult airway equipment was available, but introducing a supraglottic device was not an option since there was massive oedema of the tongue. There was no time for a tracheostomy or fiber optic intubation. Securing the airway was the major concern. The only best choice was to perform a blind nasal intubation to secure the airway. A well lubricated 6.5 cuffed nasotracheal tube was passed into the right nostril and manipulated into the larynx in a spontaneously breathing, awake patient, and intubation was done in the first attempt as the anesthetist was well trained in this technique. Once the position of the tube was confirmed and ventilation was feasible, Ketamine 75 mg and 100 mg Succinylcholine was given. The baby was delivered within 3 minutes with an APGAR of 4/10, quickly resuscitated by the pediatricians, and shifted to NICU for further management.

We continued to provide ventilator and cardiovascular support. Adrenalin was on flow. The oedema began to subside in an hour. Respiration was adequate at the end of surgery, PR = 95/min, Spo2 = 96%, BP = 100/60 mm Hg, pupils were normal and reacting. Her urine output was only 20 ml for the first two hours. She was given 2 L of crystalloids during this time. Fortunately, there was no other complications like undue blood loss. BP was now maintained with Noradrenaline infusion. Inj. Mannitol 150 ml and Inj. Lasix 20 mg was given and she was shifted to the ICU.

After 3 h, she was fully awake, without any neurological deficit. She was extubated later that day. Her urine output improved and there was no impairment in renal function.

She was referred to an allergy specialist.

Among all the patients who exhibit anaphylaxis, this patient was unique since it occurred in a pregnant patient, who was carrying a precious baby, and if we had failed to save the patient and the baby, it would spell disaster for the whole team, even if it were no fault on our part. At this juncture, I would like to recall the words of the obstetrician as told to the patient’s relatives…. “if it were not for the timely intervention, and efficient management of the anesthetists, we could have lost two lives, hence, please thank her too”.

Mother and baby were discharged home well.

Discussion

Here was a case of severe anaphylactic reaction to intravenously administered antibiotic Cephazolin. Anesthetic implications:

- Immediate diagnosis and emergency management of patient with anaphylaxis gives the patient the best chance to survive the reaction.

- IM Adrenaline 5ml 1:1000 is the suggested dose for the patient. This can be done by any health care staff. This mode of administration is better compared to subcutaneous as vasodilated muscular vasculature will absorb well and peak levels be reached in minutes. In the hand of an anesthetist or intensivist, IV Adrenaline in titrated doses may be best, to reach peak levels immediately.

- Epinephrine/Adrenaline, by virtue of its effect on alpha 1 receptors, increases vasoconstriction and increases systemic vascular resistance, raises blood pressure. By action on beta 1 receptor, increases cardiac contractility and heart rate. Action on beta 2 receptors, decreases inflammatory mediator release, thereby producing bronchodilation, decrease wheezing, reducing urticaria and rash and henceforth the angioedema, and also improving the blood pressure.

- Importance of the test dose of antibiotic: It is safe for the patient and the anesthesiologist if the test dose for the surgical prophylactic antibiotic is administered at least half an hour before starting anesthesia. This will give us time to check for any reaction at the site of inoculum. Also, patients will understand that reactions to antibiotics are not uncommon and rarely can be catastrophic. On the other hand, sometimes the test dose may sensitize the patient and the second dose may precipitate a catastrophic reaction.

Anaphylaxis is a severe, life-threatening, generalized or systemic hypersensitivity reaction. According to the World Allergy Organization, diagnosis of anaphylaxis is made if one of the following criteria is met:

- Acute/rapid development of skin, mucosal, tissue or both with generalised urticaria, itching, flushing, swelling of lips/airway structures AND one of the following (a) respiratory compromise, (b) reduced blood pressure.

- Reduced BP after exposure to allergen (several minutes to hours after exposure)

- Any two or more of the following clinical features: tissue oedema, respiratory compromise, hemodynamic compromise, persistent gastrointestinal symptoms.

Blind Nasal Intubation (BNI)

This is a technique which should not be given up. This skill is being forgotten today. Newer gadgets (if available), and the practitioner being familiar with its use, is of course the best method to secure a difficult airway. BNI may look and feel rough but is often a life saver. I would recommend that we do not give up this skill completely and surely it is not inhumane to save a life in an emergency situation like the one explained in the above case. There are a few tips which I would like to pass on.

- Check for patency of nostrils, and prepare the nostrils with vasoconstrictor drops. Use adequate lubrication.

- Upper airway block if time permits, or use liberal lignocaine jelly (not exceeding the calculated dose) Mild sedation (dexmedetomidine)

- Choose appropriate size ETT (need not be too small.)

- Position head in the sniffing in the air position.

- Introduce the tube from the nostril and go past the nasopharynx (that is the difficult step) Once you have entered the oropharynx, wait for a few seconds.

- Extend the head a little more, manipulate the larynx and keep the tube as anterior as possible. Close the other nostril.

- Never push when there is resistance

- After a successful intubation and confirmation do not inflate the cuff until the patient is anaesthetized and completely relaxed.

It is taught that BNI is contra indicated in patients with abscess around the upper airway.FOB is of course the best method to secure the airway in these patients. But in an emergency situation when the patient’s life is at stake and tracheostomy is impossible due to the massive swelling in front of the neck and FOB is not available one can resort to BNI (if well trained).

Reflexes are active and chances of aspiration is less. I have personally saved six patients using the technique of BNI to secure the airway and all of them did well post operatively.

BNI has its own drawbacks but it can be overcome with good training and skills. Further data collection and analysis is required to substantiate this statement.

It is worthwhile reconsidering the statement that BNI is absolutely contra indicated in patients with abscess around the airway.

References

- Simons FER et al. World Allergy Organization Guidelines for the Assessment and Management of Anaphylaxis. World Allergy Organ J. 2011; 4(2): 13-37.

- Anaphylaxis – Anaphylaxis: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology (medscape.com) assessed on Feb 22, 2017.

- Overview – Anaphylaxis – Mayo Clinic www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anaphylaxis/home/ovc-20307210 assessed on Feb 14, 2017.

- Anaphylaxis – Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy … https://www.allergy.org.au/patients/about-allergy/anaphylaxis.

Keep cool and think calmly when there is an emergency but be quick at reacting.

Chapter 4

Ants in the Airway

A 42-year-old plumber presented to the emergency department holding his throat. He complained of acute pain and difficulty in breathing. He found it impossible to talk and hence, no history could be elicited. Attendees mentioned that he had been working on water pipes in an old building and suddenly came running, holding his neck. It was suspected that he may have swallowed some chemical or there was a foreign body in the airway.

He was immediately wheeled into the endoscopy room for a diagnostic procedure. However, he was extremely restless with a pulse rate of 140 beats/min, BP of 85/60, and a room air SpO2 of 90%. Due to the critical state of the patient, no other investigations were done. Securing the airway and stabilizing the patient was the immediate need of the hour regardless of the cause. He was deteriorating rapidly. He was oxygenated, and 200 mg hydrocortisone was administered. There was slight improvement but he continued to be in agony, and unless the throat was examined no diagnosis could be made.

On account of his irritability, general anesthesia seemed to be only choice. All emergency drugs and airway cart were made available.

He was induced with Thiopentone 150 mg and Fentanyl 100 µg. Succinylcholine 75 mg was used as the relaxant for intubation. On insertion of the laryngoscope, the glottic opening was swarming with ants!

A 7.5 cuffed size ETT was carefully inserted avoiding injury to the already inflamed mucosa. He was maintained on controlled ventilation with Oxygen and Nitrous Oxide mixture, and Sevoflurane 1% and vecuronium. The throat was carefully packed with roller gauze. The surgeons used endoscope and forceps, and managed to remove about 30 ants from his larynx and pharynx, some of them even alive.! His vitals remained stable.

Due to the inflammation and oedema of the glottis, patient was shifted for elective post-operative ventilation for the next 24 h. He was extubated the following day after a dose of Dexamethasone 8 mg as a precautionary measure, to prevent airway oedema.

Later on, it was revealed that the patient being a plumber had been blowing and sucking on a blocked water pipe, where there had been ants. These had gone into his airway and ant bites had caused a reaction. He was discharged three days later without any sequelae.

Discussion

Interesting and challenging scenarios with unanticipated problems show up in our practice periodically. Whatever may be the picture, keeping up with the basic principles of maintaining airway, breathing and circulation makes it safe. Concerns in this case were:

- Risk of starting GA without history of even the last meal or any investigations. Hence, shorter acting drugs were chosen, and a rapid sequence induction and intubation performed.

- Securing the airway may be difficult, hence back up emergency tracheostomy was made available.

- Airway oedema can be catastrophic; use of steroids, and delaying extubation must be considered.

Reactions of some species of ants’ sting varies from mild allergic reactions to severe anaphylactic shock, and laryngeal oedema, regardless of the site of sting. In our patient, the sting was on the airway itself. Various case reports on black ant and fire ant stings have been published. However, not many have been reported from our country. Patient response may be very variable and clinical features include a wide spectrum from mild inflammatory response to severe bronchospasm and hemodynamic collapse.

Management algorithm of insect sting is similar to rapid response to anaphylaxis:

- Airway angio-oedema: Risk of loss of airway – Hence securing the airway is to be done immediately, taking all precautionary measures as in any emergency scenario. To prevent further oedema, dose of injection Adrenaline 0.1mg 1:1000 IM may be necessary in adults, particularly when combined with hypotension and cardiovascular instability. IV Adrenaline 0.1mg incremental boluses may be required if there is an impending cardiac arrest.

- Bronchoconstriction: Nebulised beta agonist should be administered. Endotracheal intubation to secure airway required in severe cases.

- Hypotension: Fluid bolus followed by vasopressor infusion may be indicated.

- Dose of antihistamine and systemic steroid to reduce inflammatory response.

Decision to Take Up a Patient in The Presence of Arrhythmias

Case 1

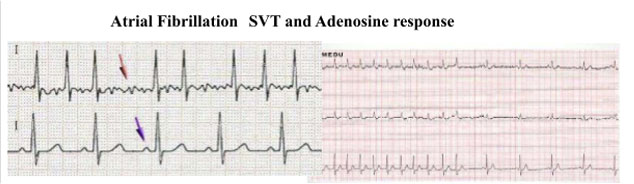

A 50-year-old man was brought to the emergency department for an obstructed inguinal hernia. He was a chronic smoker and was also under the influence of alcohol at that time. Relevant medical history was that he was a known case of cardiac arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation) and had discontinued his medication. He could not give a detailed history about the drugs or the duration of medication. On examination, his pulse rate was 115/ minute irregularly irregular, BP was 110/70, and lungs were clear. His preoperative ECG showed absent P waves with varying RR intervals. Chest X-ray was normal, and echo showed no LA clot, EF of 54 % and normal valves.

Here we had a patient with history of noncompliance to antiarrhythmic drug treatment. This patient was prone to tachyarrhythmia in the perioperative period which may compromise safety. However, due to the emergency nature of his condition, risks were explained to the patient and family, and was taken up for emergency hernioplasty.

The anesthetic goals included

- To prevent hypotension that may compromise blood supply to the coronaries and cause uncontrollable tachyarrhythmia.

- To appropriate fluid and electrolyte balance, particularly potassium and magnesium.

- To prevent thromboembolic phenomenon—Anticoagulation in form of low molecular Heparin – may need to be commenced in perioperative period.

It was decided to perform the surgery under hernia block, as it was the safest technique for this patient. (smoker, AF, under influence of alcohol). The surgery was completed as planned, and the patient made an uneventful recovery. Postoperatively after cardiology review, drugs were recommenced.

Case 2

A 60-year-old woman who was obese, hypertensive, and diabetic, with an extremely anxious personality, was posted for elective ventral hernia repair. She mentioned history of anxiety and occasional palpitations that usually settled on its own. Preoperative ECG, echo, and cardiology review were noted to be normal.

As patient was wheeled into operation theatre, she was anxious about surgery and when monitors were placed, it was noticed that her heart rate was 197- 200/min. Rhythm was recognized as supraventricular tachycardia. Patient was conscious and oriented, BP=90/46 mm Hg and oxygen saturation was 94% on air. 100% Oxygen was administered via face mask and 2 mg midazolam administered.

Chest was clear, no sign of impending heart failure. Metoprolol IV was administered slowly 2 mg boluses up to 10 mg, heart rate came down to 156/min, still in SVT. 12 lead ECG was done and Adenosine was given. However, the response was very short and hence, Amiodarone 150 mg was given slowly IV over 20 minutes, and 150mg was added to an infusion.

Rhythm converted to sinus with a rate of 76/min. Blood pressure was stable at 100/60. Surgery was cancelled for the day. It was decided to achieve rate control before elective surgery. Cardiologist reviewed the patient and diagnosed an aberrant tract causing SVT, which needed ablation. Patient underwent radiofrequency ablation in next 48 hours. One week later elective surgery was done as open procedure under epidural anaesthesia. She did not have any further cardiac event.

Discussion

Atrial fibrillation and SVT are not uncommon arrhythmias and anesthesiologists must be able to identify and manage them efficiently to prevent untoward consequences. Perioperative AF is a risk-factor for ischemic stroke, and healthcare providers should consider appropriate antiarrhythmic and antithrombotic measures in surgical patients.

In the first scenario, we had a patient who was a known case of atrial fibrillation. The management in such scenarios are:

- Preoperative control of rate and rhythm

- Preoperative echo to rule out any left atrial thrombus to prevent perioperative risk of embolus in addition to assessment of static cardiac function

- Manage perioperative anticoagulation – in patients on Warfarin, stop Warfarin and use bridge therapy with Heparin.

- Perioperative Digoxin: Drug interactions to be borne in mind.

- Avoid triggers that push to tachyarrhythmia: hypovolemia, stress, electrolyte imbalance (especially potassium) and pain. If rate control is required, beta-blockers may be used.

It is important for all practicing anesthetist, to be familiar with common regional blocks, which will come in handy in emergency situations like this.

In the second patient, we had a case of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, due to an aberrant tract, triggered in preoperative setting related to stress and anxiety, diagnosed just prior to anesthesia.

It was identified by the anesthetist at the right time prior to induction and managed successfully. If anesthesia had been induced without noticing it, patient may have suffered cardiac event under anesthesia and it may be considered as anesthetic morbidity.

Management guidelines of SVT suggest:

- Rate and rhythm control.

- Identify triggers – ischemia or aberrant tract.

- Follow algorithm as per resuscitation council guidelines.

Some patients may have atrial ectopics, and paroxysmal atrial tachycardia due to long standing effect of drugs, like in asthmatics, and COPD patients. In such patients under anesthesia, these rhythms may be benign and not persistent. They can be left alone as they are usually self-resolving provided the patient is kept hemodynamically stable and well oxygenated. It is important to avoid sympathomimetic drugs such Adrenaline infiltration in such patients which may tilt the balance and precipitate significant arrythmias.

References

- Camm AJ et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: The Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2369-429.

- NICE Guidelines: Preoperative tests for elective surgery: 2003. ALS guidelines for management of tachyarrhythmia. https://www.resus.org.uk/pages/periarst.pdf 5.

- Lip G, Douketis J. Management of anticoagulation before and after elective surgery. UpToDate, 2014.

- Algorithms for Advanced Cardiac Life Support 2017. https://www.acls.net/aclsalg.htm Algorithms for Advanced Cardiac Life Support 2017 Mar 30, 2017. Version control: This document is current with respect to 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines.