Journal scan: A review of 15 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

From the desk of the Editor-in-Chief

(1). Spellberg B, et al. Evaluation of a Paradigm Shift From Intravenous Antibiotics to Oral Step-Down Therapy for the Treatment of Infective Endocarditis. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):769-77.

Importance: The requirement of prolonged intravenous antibiotic courses to treat infective endocarditis (IE) is a time-honored dogma of medicine. However, numerous antibiotics are now available that achieve adequate levels in the blood after oral administration to kill bacteria. Moreover, prolonged intravenous antibiotic regimens are associated with high rates of adverse events. Accordingly, recent studies of oral step-down antibiotic treatment have stimulated a reevaluation of the need for intravenous-only therapy for IE.

Observations: PubMed was reviewed in October 2019, with an update in February 2020, to determine whether evidence supports the notion that oral step-down antibiotic therapy for IE is associated with inferior outcomes compared with intravenous-only therapy. The search identified 21 observational studies evaluating the effectiveness of oral antibiotics for treating IE, typically after an initial course of intravenous therapy; none found such oral step-down therapy to be inferior to intravenous-only therapy. Multiple studies described an improved clinical cure rate and an improved mortality rate among patients treated with oral step-down vs intravenous-only antibiotic therapy. Three randomized clinical trials also demonstrated that oral step-down antibiotic therapy is at least as effective as intravenous-only therapy in right-sided, left-sided, or prosthetic valve IE. In the largest trial, at 3.5 years of follow-up, patients randomized to receive oral step-down antibiotic therapy had a significantly improved cure rate and mortality rate compared with those who received intravenous-only therapy.

Conclusions and Relevance: This review found ample data demonstrating the therapeutic effectiveness of oral step-down vs intravenous-only antibiotic therapy for IE, and no contrary data were identified. The use of highly orally bioavailable antibiotics as step-down therapy for IE, after clearing bacteremia and achieving clinical stability with intravenous regimens, should be incorporated into clinical practice.

(2). DISCHARGE Trial Group, et al. CT or Invasive Coronary Angiography in Stable Chest Pain. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1591-602.

Background

In the diagnosis of obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD), computed tomography (CT) is an accurate, noninvasive alternative to invasive coronary angiography (ICA). However, the comparative effectiveness of CT and ICA in the management of CAD to reduce the frequency of major adverse cardiovascular events is uncertain.

Methods

We conducted a pragmatic, randomized trial comparing CT with ICA as initial diagnostic imaging strategies for guiding the treatment of patients with stable chest pain who had an intermediate pretest probability of obstructive CAD and were referred for ICA at one of 26 European centers. The primary outcome was major adverse cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke) over 3.5 years. Key secondary outcomes were procedure-related complications and angina pectoris.

Results

Among 3561 patients (56.2% of whom were women), follow-up was complete for 3523 (98.9%). Major adverse cardiovascular events occurred in 38 of 1808 patients (2.1%) in the CT group and in 52 of 1753 (3.0%) in the ICA group (hazard ratio, 0.70; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.46 to 1.07; P=0.10). Major procedure-related complications occurred in 9 patients (0.5%) in the CT group and in 33 (1.9%) in the ICA group (hazard ratio, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.13 to 0.55). Angina during the final 4 weeks of follow-up was reported in 8.8% of the patients in the CT group and in 7.5% of those in the ICA group (odds ratio, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.92 to 1.48).

Conclusions

Among patients referred for ICA because of stable chest pain and intermediate pretest probability of CAD, the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events was similar in the CT group and the ICA group. The frequency of major procedure-related complications was lower with an initial CT strategy.

(3). Offit PA. Covid-19 Boosters – Where from Here? N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1661-2.

On December 10, 2020, Pfizer presented results from a 36,000-person, two-dose, prospective, placebo-controlled trial of its Covid-19 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine, BNT162b2, to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The vaccine was 95% effective at preventing severe illness in all age groups, independent of coexisting conditions or racial or ethnic background. A remarkable result. Six months later, studies showed that protection against severe disease was holding up. The results of these epidemiologic studies were consistent with those of immunologic studies showing long-lived, high frequencies of Covid-19-specific memory B and T cells, which mediate protection against severe disease.

In September 2021, 10 months after the BNT162b2 vaccine had become available, Israeli researchers found that protection against severe illness in people 60 years of age or older was enhanced by a third dose. In response, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that people 65 years of age or older should receive three doses of an mRNA vaccine.

In a study now reported in the Journal, Israeli researchers found that in a study population with a median age of 72 years, protection against severe disease was further enhanced by a fourth dose of mRNA vaccine during the wave of infections caused by the B.1.1.529 (omicron) variant of SARS-CoV-2. These findings were considered by the FDA and CDC in their decision-making process regarding the use of an additional booster dose of mRNA vaccine for people 50 years of age or older.

What about booster dosing for persons who are younger? One year after the BNT162b2 vaccine became available, studies in the United States showed that a third dose of vaccine also enhanced protection against severe disease for people as young as 18 years of age. Unfortunately, these studies did not stratify patients according to whether they had coexisting conditions. Therefore, it was unclear who among these younger age groups most benefited from an additional dose. Nonetheless, the CDC later recommended that everyone 12 years of age or older should receive three doses of BNT162b2, regardless of whether risk factors were present. This universal booster recommendation led some summer camps, high schools, universities, hospitals, and businesses to require three doses of mRNA vaccine. In February 2022, in a study that did not support the booster recommendation for children, CDC researchers found that two doses of BNT162b2 induced long-lived protection against serious illness in children 12 to 18 years of age.

In addition to protection against severe disease, the initial phase 3 trial of BNT162b2 – which was performed over a period of several months – also showed 95% protection against mild illness. Unlike protection against severe illness, however, protection against mild illness, which is mediated by high titers of virus-specific neutralizing antibodies at the time of exposure, declined after 6 months, as would have been expected. In response, studies by Pfizer were published in which a booster dose was shown to restore protection against mild illness; unfortunately, this protection did not persist for more than a few months. Short-lived protection against mild illness will limit the ability of booster dosing to lessen transmission.

People are now confused about what it means to be fully vaccinated. It is easy to understand how this could happen. Arguably, the most disappointing error surrounding the use of Covid-19 vaccines was the labeling of mild illnesses or asymptomatic infections after vaccination as “breakthroughs.” As is true for all mucosal vaccines, the goal is to protect against serious illness – to keep people out of the hospital, intensive care unit, and morgue. The term “breakthrough,” which implies failure, created unrealistic expectations and led to the adoption of a zero-tolerance strategy for this virus. If we are to move from pandemic to endemic, at some point we are going to have to accept that vaccination or natural infection or a combination of the two will not offer long-term protection against mild illness.

In addition, because boosters are not risk-free, we need to clarify which groups most benefit. For example, boys and men between 16 and 29 years of age are at increased risk for myocarditis caused by mRNA vaccines. And all age groups are at risk for the theoretical problem of an “original antigenic sin” – a decreased ability to respond to a new immunogen because the immune system has locked onto the original immunogen. An example of this phenomenon can be found in a study of nonhuman primates showing that boosting with an omicron-specific variant did not result in higher titers of omicron-specific neutralizing antibodies than did boosting with the ancestral strain. This potential problem could limit our ability to respond to a new variant.

It is now incumbent on the CDC to determine who most benefits from booster dosing and to educate the public about the limits of mucosal vaccines. Otherwise, a zero-tolerance strategy for mild or asymptomatic infection, which can be implemented only with frequent booster doses, will continue to mislead the public about what Covid-19 vaccines can and cannot do.

(4). Hodgson KA, et al. Nasal High-Flow Therapy during Neonatal Endotracheal Intubation. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1627-37.

Background

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a major cause of illness and death in infants worldwide, could be prevented by vaccination during pregnancy. The efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety of a bivalent RSV prefusion F protein-based (RSVpreF) vaccine in pregnant women and their infants are uncertain.

Methods

In a phase 2b trial, we randomly assigned pregnant women, at 24 through 36 weeks’ gestation, to receive either 120 or 240 μg of RSVpreF vaccine (with or without aluminum hydroxide) or placebo. The trial included safety end points and immunogenicity end points that, in this interim analysis, included 50% titers of RSV A, B, and combined A/B neutralizing antibodies in maternal serum at delivery and in umbilical-cord blood, as well as maternal-to-infant transplacental transfer ratios.

Results

This planned interim analysis included 406 women and 403 infants; 327 women (80.5%) received RSVpreF vaccine. Most postvaccination reactions were mild to moderate; the incidence of local reactions was higher among women who received RSVpreF vaccine containing aluminum hydroxide than among those who received RSVpreF vaccine without aluminum hydroxide. The incidences of adverse events in the women and infants were similar in the vaccine and placebo groups; the type and frequency of these events were consistent with the background incidences among pregnant women and infants. The geometric mean ratios of 50% neutralizing titers between the infants of vaccine recipients and those of placebo recipients ranged from 9.7 to 11.7 among those with RSV A neutralizing antibodies and from 13.6 to 16.8 among those with RSV B neutralizing antibodies. Transplacental neutralizing antibody transfer ratios ranged from 1.41 to 2.10 and were higher with nonaluminum formulations than with aluminum formulations. Across the range of assessed gestational ages, infants of women who were immunized had similar titers in umbilical-cord blood and similar transplacental transfer ratios.

Conclusions

RSVpreF vaccine elicited neutralizing antibody responses with efficient transplacental transfer and without evident safety concerns.

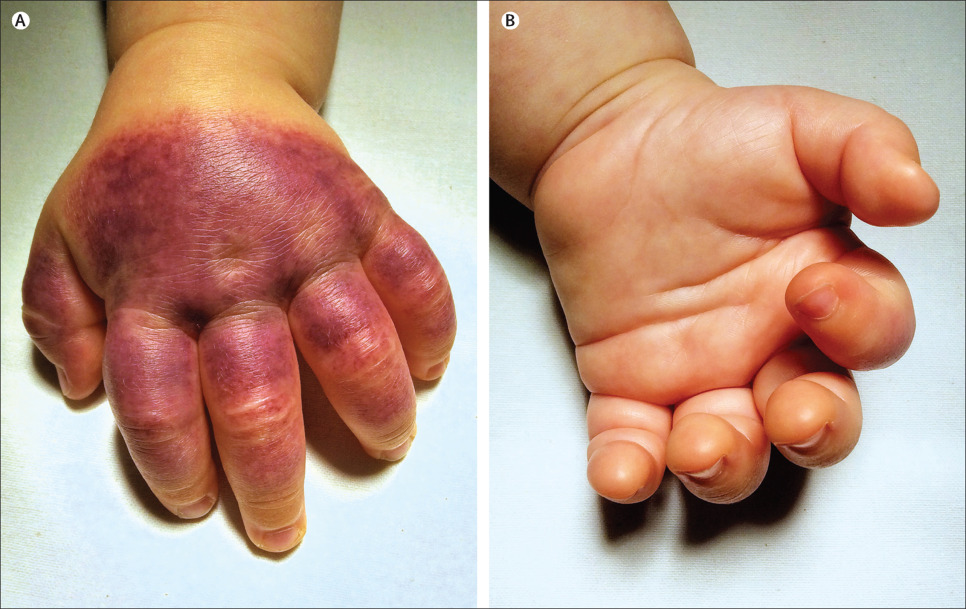

(6). Pittet LF. Striking but benign: acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy. Lancet 2022;399(10336):E41.

A previously healthy 6-month-old boy presented in September, 2014, with indurated and tender oedema of the left hand, associated with a rapidly spreading purpuric rash on the dorsum. He also had swelling of one side of his face, but examination was otherwise normal. Beginning 4 days previously he had had a 3-day upper respiratory tract infection, with no associated fever; his parents denied trauma or previous drug use. Blood tests including full blood count, coagulation studies, and circulating immune complexes were normal, apart from moderate thrombocytosis (platelets 518X109/L; normal range 168-392X109/L) and normochromic normocytic anaemia (haemoglobin 99 g/L; 105-135 g/L). Urinalysis was normal.

We diagnosed acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy, a leukoclastic small-vessel vasculitis that was initially thought to be a benign variant of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, but is now considered a distinct entity. Acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy typically affects children between 4 and 24 months of age, whereas Henoch-Schönlein purpura is more common in children aged 3 to 6 years. Unlike Henoch-Schönlein purpura, systemic involvement is rare in acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy; symptoms are usually restricted to the skin. Cutaneous lesions are typically large nummular red or purpuric plaques or cockade-like lesions involving the face, ears, and limbs, but sparing the trunk and mucosa. Non-pitting oedema is more frequently noted on the arms and legs but can involve the face. In Henoch-Schönlein purpura the legs and buttocks are more commonly affected. Patients with acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy usually look clinically well. Lesions usually resolve within 1-3 weeks without treatment. Long-term sequelae have not been reported. In our patient, the purpuric rash resolved within 4 weeks and at follow-up 6 months later he had had no further symptoms. After excluding infectious, immune, or inflammatory causes of purpuric rashes, physicians should consider this rare, striking but benign diagnosis when faced with a well-appearing infant with purpuric plaques and non-pitting oedema.

(7). Slade P. Identifying post-traumatic stress disorder after childbirth. BMJ 2022;377:e067659

What you need to know

One third of women experience giving birth as traumatic, and consequently 3-6% of all women giving birth develop postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with many going undiagnosed.Healthcare providers should ask about birth trauma routinely. Recognising early responses to a traumatic birth and providing advice and support can reduce the risk of PTSD developing. PTSD is different from postpartum depression. Although both can occur simultaneously, they require different psychological treatments. Some cases of postpartum depression can be managed in primary care, but postpartum PTSD more commonly requires specialist maternal mental health referral “My baby was in distress after a long labour, this resulted in a forceps delivery after which I haemorrhaged and sustained injury. As a new mother I felt frightened all the time, tearful and low, fearing danger around every corner. I was afraid to put my baby down to sleep, or to even walk down the stairs with my new son in my arms. I experienced nightmares and replayed the birth over in my head, wondering what could have happened differently and what I wish I could have changed. I had scary intrusive thoughts that I was concerned to disclose for fear of being judged a bad mother. I felt forever changed mentally and physically by the birth, and wondered if I would ever feel myself again. I loved being a mother and felt guilty that I was struggling. It was a very lonely time as there was no one to talk to who understood or could point me in the right direction for help. My husband knew I was struggling, but was at a loss to know what to do, so we both did our best to attempt to deal with things alone.”

One in three people will find giving birth a traumatic experience.

(8). Smith R. Kindness and effective care depend on close observation: reflections from a deathbed. BMJ 2022;377:o1155.

Much of good care is little things, things that are not heroic and are not measured, but make all the difference between good and poor care. Unintended lack of kindness might be something like giving a dying person tea with milk when they drink only black coffee. This happened to my mother, and something similar, but a bit more serious is happening now with my mother.

My mother is close to death. Indeed, she looks more like a corpse than a living person. I sat with her for some four hours yesterday, and mostly she was calm, sleeping, and just occasionally groaning. But as time passed she became more uncomfortable. The nurse and I debated whether she should have a small dose of morphine. The obvious discomfort she felt when turned decided me that she definitely needed an injection. The nurse agreed, but the whole process took time because they have to get two qualified nurses to inject morphine.

I wondered if even a small dose of morphine might kill her, but it didn’t. She became calmer, but the effect began to fade. I suggested that they might give her another injection, but they said that they would have to wait for four hours. I expected that they would give the injections regularly during the night.

When I arrived this morning my mother was clearly distressed. They were planning to wash her. I said that I thought that they ought to give her an injection before they did so and asked if she had had an injection during the night. The nurse didn’t know and said she would check the system and added that she would have had an injection “only if the nurse thought she needed it.” The nurse came back a few minutes later and said how she hadn’t had an injection. I pointed out that it’s better to prevent pain than try and treat it when it’s arrived.

They agree that they will give her an injection and suspend the washing until she’s comfortable. Unfortunately, it takes about 30 minutes to assemble two nurses. During that time I suggest that they might give her twice the dose they gave her yesterday. The nurse says she’d have to get a doctor’s permission to do that, and, as this is a care home there is no doctor available.

As it happens, it appears that the nurse hadn’t read the instructions left by the palliative care team. They can give twice the dose she had yesterday, and she can have it every hour if necessary. They gave her the injection 10 minutes ago, and the morphine is having its sweet effect.

Nobody here is unkind. The nurses and carers want to do their best, and they show their kindness by offering me tea every few minutes. But to be effective kindness needs close observation and a thoughtfulness that probably eludes most of us. The nurses and carers live as well in terror of the “rules, the system,” especially when it comes to opiates. Lack of close observation and the need to follow the rules have unnecessarily led to suffering for my mother. But now she is very calm in the embrace of Morpheus.

A week later: That last dose of morphine was enough. My mother didn’t need any more and died peacefully 15 hours after that injection. My brothers and I prepared to celebrate a rich life filled with love and caring, and her death has led me to reflect on the world’s most difficult job, being a mother.

(9). Mahase, E. Monkeypox: What do we know about the outbreaks in Europe and North America? BMJ 2022;377:o1274.

Monkeypox, a virus first discovered in monkeys in 1958 and that spread to humans in 1970, is now being seen in small but rising numbers in Western Europe and North America. Elisabeth Mahase summarises what we know so far

How many cases have been confirmed?

Case numbers seem to be rising daily though are still low. In England nine cases were confirmed between 6 and 18 May.Meanwhile, Spain has reported 23 potential but unconfirmed cases, and Portugal has confirmed five of its 20 suspected cases. One case in the US has been confirmed.

How is it spreading?

Transmission between people mostly occurs through large respiratory droplets, normally meaning prolonged contact face to face. But the virus can also spread through bodily fluids. The latest cases have mainly been among men who have sex with men.

The UK Health Security Agency said that, although monkeypox has not previously been described as a sexually transmitted infection, it can be passed on by direct contact during sex. It can also be passed on through other close contact with a person who has monkeypox or contact with clothing or linens used by a person who has monkeypox.

Inger Damon, director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of High Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, said, “Many of these global reports of monkeypox cases are occurring within sexual networks. However, healthcare providers should be alert to any rash that has features typical of monkeypox. We’re asking the public to contact their healthcare provider if they have a new rash and are concerned about monkeypox.”

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms can include fever, headache, muscle aches, backache, swollen lymph nodes, chills, and exhaustion. Typically a rash will develop, which often starts on the face but can then spread to other areas such as the genitals. The rash will go through different stages before forming a scab that finally falls off. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) said that the recent cases among men who have sex with men have involved lesions in the genital area.

Is monkeypox deadly and can it be treated?

Generally, monkeypox cases are mild and people tend to recover within weeks. But the death rate varies, depending on the type. The ECDC has said that the west African clade, the type so far seen in Europe, has a case fatality rate of around 3.6% (estimated from studies conducted in African countries). Mortality is higher in children, young adults, and immunocompromised individuals.

Michael Head, senior research fellow in global health at the University of Southampton, said, “The risks to the wider UK public are extremely low, and we do have healthcare facilities that specialise in treating these tropical infections. However, with tropical medicine, these imported cases do indicate a wider burden of disease elsewhere in the world. It may be that in a post-pandemic environment we should be giving more consideration to understanding the local and global implications of Lassa, monkeypox, Ebola, and other rare but serious pathogens.”

Although there are no specific treatments for monkeypox, the smallpox vaccine-which has been shown to be up to 85% effective in preventing monkeypox-and the antivirals cidofovir and tecovirimat can be used to control outbreaks.6 The UK government has reportedly bought thousands of vaccine doses and already begun deploying them among close contacts of infected people.

Have the US and Europe seen previous major outbreaks?

In 2003 the US had an outbreak of 47 confirmed and probable cases linked to a shipment of animals from Ghana. Everyone infected with monkeypox became ill after contact with pet prairie dogs that had been infected after being housed near the imported small mammals.

Seven previous cases of monkeypox have been reported in the UK (in 2018, 2019, and 2021), mainly among people with a history of travel to endemic countries. However, the ECDC has said that this latest outbreak is the first time that chains of transmission have been reported in Europe without known epidemiological links to west and central Africa, and they are also the first cases reported among men who have sex with men.

In a statement it said, “Given the unusually high frequency of human-to-human transmission observed in this event, and the probable community transmission without history of travelling to endemic areas, the likelihood of further spread of the virus through close contact, for example during sexual activities, is considered to be high. The likelihood of transmission between individuals without close contact is considered to be low.”

(10). Jacobs DR, et al. Childhood Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Adult Cardiovascular Events. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1877-88.

Background

Childhood cardiovascular risk factors predict subclinical adult cardiovascular disease, but links to clinical events are unclear.

Methods

In a prospective cohort study involving participants in the International Childhood Cardiovascular Cohort (i3C) Consortium, we evaluated whether childhood risk factors (at the ages of 3 to 19 years) were associated with cardiovascular events in adulthood after a mean follow-up of 35 years. Body-mass index, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol level, triglyceride level, and youth smoking were analyzed with the use of i3C-derived age- and sex-specific z scores and with a combined-risk z score that was calculated as the unweighted mean of the five risk z scores. An algebraically comparable adult combined-risk z score (before any cardiovascular event) was analyzed jointly with the childhood risk factors. Study outcomes were fatal cardiovascular events and fatal or nonfatal cardiovascular events, and analyses were performed after multiple imputation with the use of proportional-hazards regression.

Results

In the analysis of 319 fatal cardiovascular events that occurred among 38,589 participants (49.7% male and 15.0% Black; mean [±SD] age at childhood visits, 11.8±3.1 years), the hazard ratios for a fatal cardiovascular event in adulthood ranged from 1.30 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.14 to 1.47) per unit increase in the z score for total cholesterol level to 1.61 (95% CI, 1.21 to 2.13) for youth smoking (yes vs. no). The hazard ratio for a fatal cardiovascular event with respect to the combined-risk z score was 2.71 (95% CI, 2.23 to 3.29) per unit increase. The hazard ratios and their 95% confidence intervals in the analyses of fatal cardiovascular events were similar to those in the analyses of 779 fatal or nonfatal cardiovascular events that occurred among 20,656 participants who could be evaluated for this outcome. In the analysis of 115 fatal cardiovascular events that occurred in a subgroup of 13,401 participants (31.0±5.6 years of age at the adult measurement) who had data on adult risk factors, the adjusted hazard ratio with respect to the childhood combined-risk z score was 3.54 (95% CI, 2.57 to 4.87) per unit increase, and the mutually adjusted hazard ratio with respect to the change in the combined-risk z score from childhood to adulthood was 2.88 (95% CI, 2.06 to 4.05) per unit increase. The results were similar in the analysis of 524 fatal or nonfatal cardiovascular events.

Conclusions

In this prospective cohort study, childhood risk factors and the change in the combined-risk z score between childhood and adulthood were associated with cardiovascular events in midlife.

(11). Montgomery RA, et al. Results of Two Cases of Pig-to-Human Kidney Xenotransplantation. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1889-98.

Background

Xenografts from genetically modified pigs have become one of the most promising solutions to the dearth of human organs available for transplantation. The challenge in this model has been hyperacute rejection. To avoid this, pigs have been bred with a knockout of the alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase gene and with subcapsular autologous thymic tissue.

Methods

We transplanted kidneys from these genetically modified pigs into two brain-dead human recipients whose circulatory and respiratory activity was maintained on ventilators for the duration of the study. We performed serial biopsies and monitored the urine output and kinetic estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) to assess renal function and xenograft rejection.

Results

The xenograft in both recipients began to make urine within moments after reperfusion. Over the 54-hour study, the kinetic eGFR increased from 23 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 of body-surface area before transplantation to 62 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 after transplantation in Recipient 1 and from 55 to 109 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 in Recipient 2. In both recipients, the creatinine level, which had been at a steady state, decreased after implantation of the xenograft, from 1.97 to 0.82 mg per deciliter in Recipient 1 and from 1.10 to 0.57 mg per deciliter in Recipient 2. The transplanted kidneys remained pink and well-perfused, continuing to make urine throughout the study. Biopsies that were performed at 6, 24, 48, and 54 hours revealed no signs of hyperacute or antibody-mediated rejection. Hourly urine output with the xenograft was more than double the output with the native kidneys.

Conclusions

Genetically modified kidney xenografts from pigs remained viable and functioning in brain-dead human recipients for 54 hours, without signs of hyperacute rejection.

(12). Devereaux PJ, et al. Tranexamic Acid in Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery. N Engl J Med. 2022 May 26;386(21):1986-1997.

Background

Perioperative bleeding is common in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic drug that may safely decrease such bleeding.

Methods

We conducted a trial involving patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Patients were randomly assigned to receive tranexamic acid (1-g intravenous bolus) or placebo at the start and end of surgery (reported here) and, with the use of a partial factorial design, a hypotension-avoidance or hypertension-avoidance strategy (not reported here). The primary efficacy outcome was life-threatening bleeding, major bleeding, or bleeding into a critical organ (composite bleeding outcome) at 30 days. The primary safety outcome was myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery, nonhemorrhagic stroke, peripheral arterial thrombosis, or symptomatic proximal venous thromboembolism (composite cardiovascular outcome) at 30 days. To establish the noninferiority of tranexamic acid to placebo for the composite cardiovascular outcome, the upper boundary of the one-sided 97.5% confidence interval for the hazard ratio had to be below 1.125, and the one-sided P value had to be less than 0.025.

Results

A total of 9535 patients underwent randomization. A composite bleeding outcome event occurred in 433 of 4757 patients (9.1%) in the tranexamic acid group and in 561 of 4778 patients (11.7%) in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.76; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.67 to 0.87; absolute difference, -2.6 percentage points; 95% CI, -3.8 to -1.4; two-sided P<0.001 for superiority). A composite cardiovascular outcome event occurred in 649 of 4581 patients (14.2%) in the tranexamic acid group and in 639 of 4601 patients (13.9%) in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.92 to 1.14; upper boundary of the one-sided 97.5% CI, 1.14; absolute difference, 0.3 percentage points; 95% CI, -1.1 to 1.7; one-sided P=0.04 for noninferiority).

Conclusions

Among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery, the incidence of the composite bleeding outcome was significantly lower with tranexamic acid than with placebo. Although the between-group difference in the composite cardiovascular outcome was small, the noninferiority of tranexamic acid was not established2.

(13). Desai N, et al. Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. 2022.

Aman in his 70s with stage III colon cancer presented to a new primary care clinician to establish care. His only symptoms were numbness and occasional tingling in his fingers and toes. Eight months before, he had completed 3 months of adjuvant chemotherapy with capecitabine and oxaliplatin. His symptoms had started during the last month of chemotherapy, worsened for 2 months, and remained stable since. He had trouble tying his shoes and putting up delicate Christmas ornaments with his grandchildren. His only medication was losartan. He had no other neurological deficits.

The primary care clinician diagnosed chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) and prescribed gabapentin, 100 mg, capsules thrice daily. At an appointment 4 weeks later, he reported feeling drowsy and tired. The CIPN symptoms were unchanged. Gabapentin treatment was discontinued. The patient experienced nausea and insomnia on discontinuation.

At a follow-up appointment 3 months later, he reported no change in symptoms. He lamented not receiving specific information on CIPN before, during, or after chemotherapy.

Teachable Moment

Chronic CIPN is a common and distressing condition for people with cancer treated with certain chemotherapy drugs. A systematic review and meta-analysis of over 4000 patients with any cancer treated with any chemotherapy reported a CIPN prevalence of 68.1% in the first month of chemotherapy and 30.0% at 6 months. People with CIPN can experience bothersome symptoms that interfere with daily activities, physical decline and disability, and falls twice as often as those without CIPN (median, 0.7 falls per year) even years later. Given the lack of good tools to reverse CIPN, both the prevalence of CIPN and the persistence of its symptoms mark it as a key issue in cancer survivorship.

The risk of CIPN varies by chemotherapy-level and patient-level factors. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy can refer to an acute neuropathy (usually self-limited and resolving within days of each chemotherapy administration) or chronic CIPN (the topic of current discussion), which is a dose-dependent and cumulative toxic effect. It typically causes a symmetric sensory axonal neuropathy with symptoms beginning in the fingers and toes and progressing proximally (“stocking-glove”). Most patients experience numbness and tingling initially; pain usually occurs later. Motor and autonomic involvement are not very common. Chronic CIPN can continue to worsen for a few months after stopping chemotherapy (called a coasting phenomenon). Although some patients experience gradual improvement over time, most patients have residual symptoms, even years later. With a clear temporal association of chemotherapy and classic symptoms, CIPN is typically a clinical diagnosis

Approach to Managing Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (CIPN)

Medical History

Prior, recent, or ongoing treatment with:

Taxanes such as paclitaxel.

Platinums such as oxaliplatin.

Vinca alkaloids such as vincristine.

Proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib.

These are often used to treat breast cancer, colon cancer, lung cancer, lymphoma, myeloma, and ovarian cancer.

Symptoms:

Sensory symptoms such as tingling, “pins and needles,” numbness, burning pain, jabbing pain, sensitivity to touch, sensitivity to cold.

Motor symptoms such as tremors, poor coordination, loss of balance, cramps, weakness.

Autonomic symptoms such as orthostatic hypotension or constipation.

Assess comorbid symptoms such as sleep disturbances, anxiety, depression, or pain.

Assess comorbid conditions such as diabetes that may cause or worsen neuropathy.

Temporal relationship between chemotherapy and symptoms.

Chronic CIPN typically has an onset of weeks to months after initiating chemotherapy.

Symptoms can also flare up in between relative periods of stability.

Physical Examination

Check for pinprick hyperalgesia and allodynia.

Examine sensation on hands and feet.

Evaluate gait and ability to perform fine movements (pick a coin from off the floor, button a shirt).

Bloodwork and Imaging

No specific bloodwork, imaging, or electromyography is usually needed to diagnose CIPN.

Patients with baseline (prechemotherapy) neuropathy should undergo workup to prevent worsening with chemotherapy (eg, hemoglobin A1c, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and vitamin B12 testing in the appropriate setting).

Testing should be pursued if there is diagnostic confusion. For example, asymmetric neuropathy or predominantly motor neuropathy should prompt workup of other neuropathies.

Assessing Severity With Common Terminology Criteria For Adverse Events (CTCAE)

Grade 1: Asymptomatic or mild symptoms.

Grade 2: Moderate symptoms, limiting instrumental activities of daily living.

Grade 3: Severe symptoms, limiting self-care activities of daily living.

Managing CIPN

Ask patients how CIPN is affecting them and their daily lives.

Counsel patients on natural course (possibly slow gradual improvement in symptoms but that most patients have residual symptoms) and safety and fall prevention:

General safety:

Avoid exposure to extreme temperatures and prolonged contact with cold objects (eg, drink).

Caution with activities such as gardening, cooking (eg, use gloves while washing dishes).

Hand and foot care.

Fall prevention:

For gait instability, use an assistive device.

Use comfortable, skid-proof shoes.

Address home safety-no slippery floors, loose rugs, or cluttered rooms or hallways.

Install handrails throughout the home.

Interventions to Consider

Refer to rehabilitation and targeted exercise programs-consider stability, balance, and gait before engaging in exercise. Consider additional safety precautions (eg, dumbbells with soft coating) with exercise and equipment.

For painful neuropathy, consider prescribing a short trial of oral medication such as duloxetine or topical medication such as menthol (limited high-quality data).

Avoid prescribing for nonpainful symptoms like numbness or tingling because pharmacologic interventions only target pain symptoms.

Nonpharmacologic interventions such as exercise and integrative medicine may help with CIPN symptoms, and more broadly.

Educate patients about reporting back with an update on symptoms, check back with patients.

Information to share with patients: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2726030

No drugs have shown efficacy in preventing CIPN. In clinical practice, for patients who develop CIPN with ongoing chemotherapy, oncologists often alter the chemotherapy plan (chemotherapy delays, dose reduction, substitution, or discontinuation) to prevent worsening CIPN. For nononcologists evaluating patients with CIPN, a first step is assessing CIPN severity and effect on daily activities, and communicating with the oncology care team, so they can assess and consider chemotherapy changes.

For patients with established CIPN with no ongoing or planned neurotoxic chemotherapy, the focus should be on preventing injury and disability and providing symptomatic relief. No medications consistently improve nonpainful symptoms such as numbness and/or tingling. Yet prescribing is common, and is associated with burdens of obtaining and taking medications, physical harm, drug interactions, financial burden, and the opportunity costs of not providing more appropriate treatments, including counseling. For patients with painful CIPN, duloxetine may offer a small improvement in pain. In 1 clinical trial of more than 200 patients with painful CIPN (pain score >3 of 10), daily duloxetine improved mean pain scores by 1.1 point (vs 0.3 points with placebo) over 5 weeks. The American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines recommend that clinicians may offer duloxetine for patients experiencing painful CIPN. Duloxetine or other similar agents do not reverse the disease course and only provide analgesia.

We recognize that CIPN can cause great distress. In the absence of effective treatments and high-quality data, a short, judicious trial of off-label medications can be considered in certain patients with painful CIPN. In our own practice, we sometimes prescribe short trials (2-3 weeks) of medications. If no benefit, we taper the medication because abrupt discontinuation can precipitate withdrawal. Prescriptions can also be considered for patients with comorbid sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression. Along these lines, European guidelines suggest consideration of medication trials (venlafaxine, gabapentinoids, or tricyclic antidepressants) in select patients with painful CIPN. Topical medications (eg, menthol) and nonpharmacologic interventions (eg, exercise, acupuncture) may also be considered given low harm and potential additional health benefits (eg, with exercise). Guidelines acknowledge that evidence is often severely limited, informed by small trials, single-arm studies, and data from other neuropathies.

For all patients, clinicians should assess the effect of CIPN on daily activities, counsel regarding lifestyle changes to prevent injury, and refer appropriate patients to rehabilitation programs. This patient was inappropriately prescribed gabapentin for nonpainful CIPN, which was then discontinued abruptly leading to withdrawal, and received no counseling on CIPN across the care continuum.

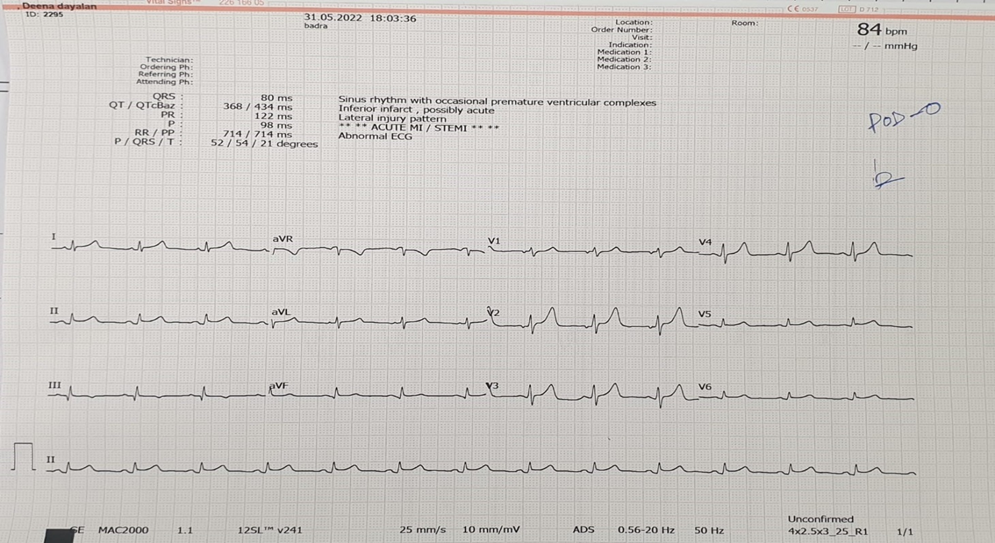

(14). Wang H, et al. Diagnostic Traps-Noteworthy Electrocardiogram Patterns. JAMA Intern Med. 2022.

A patient in the 40s was transported to the emergency department by ambulance for sudden acute chest pain that had been present for 1 hour. The patient did not have dyspnea or history of cardiac disease. The electrocardiogram (ECG) obtained in the ambulance is shown in the Figure, A. In the ambulance, the patient received nitroglycerin intravenously. On arrival, the patient’s temperature was 36.4 °C, heart rate was 76 beats/min, and blood pressure was 90/56 mm Hg. Jugular distention was visible. No crackles were auscultated in the lungs. The initial serum troponin I and D-dimer levels were 0.03 ng/mL (normal range, <=0.05 ng/mL; to convert to µg/L, multiply by 1.0) and 0.32 μg/mL (normal range, 0-0.55 μg/mL; to convert to nmol/L, multiply by 5.476), respectively. Peripheral oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. In the emergency department, a right ventricular and posterior wall ECG was obtained (Figure, B). Transthoracic echocardiography revealed severe global systolic dysfunction of the right ventricle (RV) with akinesia of the RV free wall and normal left ventricular systolic function.

A, The initial electrocardiogram demonstrated accelerated atrioventricular junctional rhythm, ST-segment elevation (STE) in leads V1 and aVR (V1>aVR), and diffuse ST-segment depression in leads I, aVL, and V3 to V6. No obvious ST-segment deviation was seen in leads II, III, and aVF. B, The electrocardiogram obtained in the emergency department demonstrated STE in leads V3R to V5R and 2 ventricular premature contractions (black arrowheads).

Question: According to these ECGs, where is the culprit lesion?

Interpretation

The initial ECG (Figure, A) demonstrated accelerated atrioventricular junctional rhythm, ST-segment elevation (STE) in leads V1 and aVR (V1>aVR), and diffuse ST-segment depression (STD) in leads I, aVL, and V3 to V6. No obvious ST-segment deviation was seen in leads II, III, and aVF. The ECG (Figure, B) obtained in the emergency department demonstrated STE in leads V3R to V5R and 2 ventricular premature contractions (black arrowheads).

Clinical Course

Coronary angiography showed no notable obstruction in the left main coronary artery, but total occlusion of the proximal nondominant right coronary artery (RCA) was present. A drug-eluting stent was placed in the RCA. The ECG showed that the patient had reverted to sinus rhythm after percutaneous coronary intervention. Based on the patient’s symptoms (acute chest pain), signs (jugular distention), and ECG, echocardiography, and coronary angiography findings, the patient was diagnosed with isolated RV myocardial infarction (IRVMI). The patient was discharged 7 days later.

Discussion

Unlike the research on left ventricular myocardial infarction (MI), studies focusing on IRVMI as a separate entity began relatively late (in 1974). It occurs in fewer than 3% of all patients with MI, and its diagnosis may be challenging.1 The most common culprit lesions causing IRVMI include occlusion of nondominant RCA or the occlusion of RV branch or RV marginal branch of RCA because these vessels supply the RV free wall. Clinical presentation of IRVMI may be very distinct. The classic triad consists of hypotension, clear lung fields, and raised jugular venous pressure.2 The ECG plays an important role in establishing the diagnosis. There are 2 main ECG patterns of IRVMI.

The first main pattern is STE in right-sided leads. This ECG pattern constitutes STE in leads aVR and V1 (V1>aVR), either accompanied or not by modest STE in lead III, and extensive STD in other leads. If right-sided leads are placed, STE in leads V3R to V5R can be observed. Anatomically, the RV forms the right anterior and inferior region of the heart. When IRVMI occurs, the transverse ST vector points rightward and anteriorly, resulting in STE in right-sided leads. The frontal ST vector may point horizontally to the right; therefore, there will be STE in lead III but no other inferior leads. In addition, because lead V1 faces the anterior region of the RV as well as the right upper paraseptal region,3 STE in lead V1 is greater than that in lead aVR.

This ECG pattern can be confused with the ECG changes of multivessel ischemia or left main coronary artery obstruction. An STD of 1 mm or greater present in 8 or more surface leads, coupled with STE in aVR and/or V1 (aVR>V1), suggests multivessel ischemia or left main coronary artery obstruction.4 In the ECG of the current patient, the STE in aVR was smaller than that in V1, and STD occurred in only 6 leads. Therefore, these findings do not resemble the ECG changes of multivessel ischemia or left main coronary artery obstruction.

The second main pattern is STE in anterior leads. This ECG pattern includes decreasing STE from V1/V2 to V4/V5 with no apparent Q waves and no reciprocal STD in inferior leads.5,6 When IRVMI leads to RV enlargement, there will be clockwise transposition of the heart, resulting in STE in anterior leads. Because V1 is located directly over the RV, STE in V1 is greater than that in V2 and V3. In addition, when the frontal ST vector points horizontally to the front, there will be no ST-segment deviation in inferior leads. This ECG pattern can be easily misdiagnosed as acute anteroseptal or anterior MI. Differentiation of IRVMI from these MIs can be achieved by observing whether the amplitudes of STE in anterior leads are increasing or decreasing from V1 to V5 and/or whether STDs are present in inferior leads.

Differentiating between RV and left ventricle infarctions is essential because an adequate preload is needed in the former, whereas vasodilators should be avoided.7 In patients who are hypotensive with RV failure, the first-line treatment is augmentation of RV preload by administering boluses of intravenous fluids. Nitrates and diuretics may worsen the hemodynamic status of these patients because they cause venodilation, which reduces the RV preload. In the case presented, the emergency personnel wrongly administered nitroglycerin, which led to a drop in blood pressure. This should be avoided as much as possible.

Take-home Points

An IRVMI occurs in fewer than 3% of all patients with MI, and its diagnosis may be challenging.

The classic triad of IRVMI consists of hypotension, clear lung fields, and raised jugular venous pressure.

There are 2 main ECG patterns of IRVMI: (1) STEs in right-sided leads and (2) STEs in anterior leads.

Differentiating between IRVMI and left ventricular infarctions is important for formulating an appropriate management plan.

Nitrates and diuretics may worsen the hemodynamic status of patients with IRVMI

(15). Arcari L, et al. Gender Differences in Takotsubo Syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79 (21):2085-2093.

Background

Male sex in takotsubo syndrome (TTS) has a low incidence and it is still not well characterized.

Objectives

The aim of the present study is to describe TTS sex differences.

Methods

TTS patients enrolled in the international multicenter GEIST (GErman Italian Spanish Takotsubo) registry were analyzed. Comparisons between sexes were performed within the overall cohort and using an adjusted analysis with 1:1 propensity score matching for age, comorbidities, and kind of trigger.

Results

In total, 286 (11%) of 2,492 TTS patients were men. Male patients were younger (age 69 ± 13 years vs 71 ± 11 years; P = 0.005), with higher prevalence of comorbid conditions (diabetes mellitus 25% vs 19%; P = 0.01; pulmonary diseases 21% vs 15%; P = 0.006; malignancies 25% vs 13%; P < 0.001) and physical trigger (55 vs 32% P < 0.01). Propensity-score matching yielded 207 patients from each group. After 1:1 propensity matching, male patients had higher rates of cardiogenic shock and in-hospital mortality (16% vs 6% and 8% vs 3%, respectively; both P < 0.05). Long-term mortality rate was 4.3% per patient-year (men 10%, women 3.8%). Survival analysis showed higher mortality rate in men during the acute phase in both cohorts (overall: P < 0.001; matched: P = 0.001); mortality rate after 60 days was higher in men in the overall (P = 0.002) but not in the matched cohort (P = 0.541). Within the overall population, male sex remained independently associated with both in-hospital (OR: 2.26; 95% CI: 1.16-4.40) and long-term mortality (HR: 1.83; 95% CI: 1.32-2.52).

Conclusions

Male TTS is featured by a distinct high-risk phenotype requiring close in-hospital monitoring and long-term follow-up.