Journal Scan

A review of 10 recent papers of immediate clinical significance, harvested from major international journals

From the desk of the Editor-in-Chief

(1). Min A. Page Kidneys. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:673.

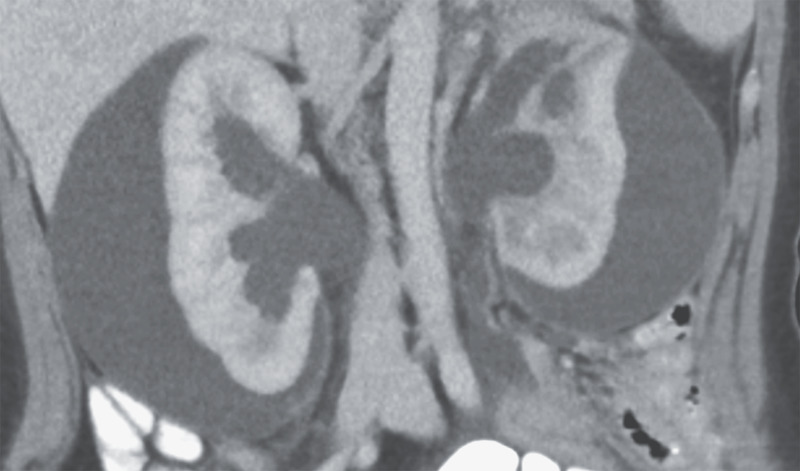

A 21-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a 6-week history of abdominal pain and constipation. Her blood pressure was 162/108 mm Hg. She had a history of Hirschsprung’s disease and had undergone a partial colectomy and pull-through procedure during infancy. She had no history of hypertension or renal disease and reported no recent flank pain or hematuria. No abdominal or costovertebral-angle tenderness was present on physical examination. The serum creatinine level was 3.6 mg per deciliter (320 μmol/L; reference range, 0.6 to 1.0 mg/dL [50 to 90 μmol/L]). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed large subcapsular urinomas on both sides and hydronephrosis caused by distal ureteral obstruction from a rectal mass. After percutaneous drainage of the urinomas, the patient’s blood pressure normalized, which confirmed the diagnosis of secondary hypertension due to external compression of the renal parenchyma. This phenomenon, known as Page kidney, occurs when outer pressure on one or both kidneys impedes renal blood flow and results in increased renin secretion. The patient underwent ureteral stenting and biopsy of the rectal mass; histologic testing showed mucinous rectal adenocarcinoma. She was referred to the medical and surgical oncology departments for further treatment.

(2). Mehta I, Patel K. Lymphatic Plastic Bronchitis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(8):e19.

A 36-year-old man with obesity presented to the pulmonary clinic with a 3-year history of shortness of breath, wheezing, and “coughing up a lung. He reported having daily expectoration of large, branching bronchial casts and brought a photograph of such a cast to the appointment. His oxygen saturation was 85% while he was breathing ambient air, and his respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute. On auscultation, scattered wheezes were heard throughout all lung fields. He was admitted to the hospital to receive supplemental oxygen and undergo further evaluation. A computed tomographic scan of the chest showed diffuse ground-glass opacities. Histopathological analysis of a bronchoalveolar-lavage sample revealed neutrophil-predominant mucus plugs and lipid-laden macrophages without evidence of bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial infection. Results of a diagnostic workup for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, and asthma were unremarkable. The patient subsequently underwent dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiography, which revealed an occlusion of the thoracic duct, a finding that suggested a diagnosis of lymphatic plastic bronchitis. Although plastic bronchitis typically manifests during childhood, the disorder can occur in adults as a result of aberrant pulmonary lymphatic flow and may lead to fatal asphyxiation if left untreated. The patient underwent percutaneous lymphatic embolization and had complete resolution of symptoms.

(3). Iacobucci G. Covid-19: Antibodies after AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccines decrease with age and are higher in women, data show. BMJ 2022;376:o428

SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels after receiving the AstraZeneca or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine decrease with age and are higher in females and people with prior infection, show data from the Real-time Assessment of Community Transmission (React-2) study.

The study, led by Imperial College London, analysed self-reported results from Fortress lateral flow tests to detect antibodies in a drop of blood from a finger prick. Data were collected from 212 102 adults from January to May 2021, of whom 71 923 (33.9%) had received at least one dose of Pfizer-BioNTech and 139 067 (65.6%) at least one dose of AstraZeneca.

Results published in Nature Communications showed that, after either of the vaccines, antibody positivity peaked four to five weeks after the first dose and then declined until after second doses were given. “For both vaccines, there was a clear increase in the proportion of individuals testing positive after second doses,” the researchers said.

Of 68 060 adults who had received their second vaccine dose at least 21 days earlier, nearly 100% of respondents had antibodies to the virus after a second dose of Pfizer. The figure dropped significantly in people who had AstraZeneca, particularly in the oldest age groups (72.7% (95% confidence interval 70.9% to 74.4%) at age 75 and above). Overall, antibody positivity was higher in those who had received the Pfizer vaccine rather than AstraZeneca (odds ratio 3.67 (3.49 to 3.85)).

Data on both vaccines showed that antibody positivity was lower in older people, with an odds ratio of 0.30 (0.24 to 0.37) in those aged over 75 versus those aged 35-44; higher in women than men (1.37 (1.30 to 1.43)); and higher in people with prior infection (2.39 (2.18 to 2.63)).

After two vaccine doses, antibody positivity was substantially lower (0.16 (0.12 to 0.22)) in people who reported being an organ transplant recipient or having a weakened immune system from illness or treatment. Positivity was also lower in people with diabetes, stroke, kidney, liver, lung or neurological disease, cancer, and depression.

Key groups

The researchers said, “These population data confirm the importance of second vaccine doses and provide strong evidence for the role of individual factors (particularly age, sex, prior infection, adiposity and comorbidities) and vaccine type in determining antibody response, particularly after first doses.

“Whilst simplicity is key to successful vaccine rollout, this information identifies key groups that may benefit from additional vaccine doses when available.”

But they added that antibody positivity was “only one measure of a multifaceted immune response,” noting that T cell response persists for at least six to eight months and that B cell mediated immunity can be sustained at least 12 months after initial infection.

They concluded, “It is possible many individuals will have sufficiently preserved immunity after two vaccine doses to prevent severe disease, but further follow-up is required to determine the longevity of protection.”

(4). Singh H. Five strategies for clinicians to advance diagnostic excellence. BMJ 2022;376:e068044.

What we need to know

The World Health Organization and the National Academy of Medicine (US) have identified measuring and reducing diagnostic error as a patient safety priority

Diagnosis is a process that is influenced by systems, cognitive, teamwork, and social factors that may either enhance or reduce diagnostic accuracy

Clinicians can integrate diagnostic performance feedback into their day-to-day work

Clinicians can take steps to mitigate biases (regarding race, ethnicity, gender, and other identities) that run counter to their values and impair diagnostic performance

Clinicians can integrate the expertise of other health professionals, patients, and families to reimagine the routines and culture around diagnosis

Diagnostic accuracy is an important component of clinical excellence. However, diagnostic errors-failures to establish an accurate and timely explanation of a patient’s health problem or to communicate that explanation to the patient-harm patients worldwide. In a recent UK study, diagnostic errors occurred in 4.3% of primary care consultations. A meta-analysis estimated that nearly 250,000 harmful diagnostic errors occur annually among hospitalised adults in the United States. The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine’s report Improving Diagnosis in Health Care highlighted that most people will experience at least one diagnostic error in their lifetime. The World Health Organization now identifies measuring and reducing diagnostic error as a patient safety priority.

Diagnostic excellence involves making a correct and timely diagnosis using the fewest resources while maximising patient experience and managing uncertainty. Compared with other patient safety problems such as medication errors, procedural complications, and hospital acquired infections, diagnostic errors have received less investigation. Diagnoses are rendered by clinicians but health system vulnerabilities frequently influence clinical reasoning and contribute to diagnostic error.

While system interventions are essential to achieving diagnostic excellence, this article focuses on the individual clinician.

(5). Habib AR, et al. Predicting covid-19 outcomes. BMJ 2022;376:o354.

As of mid-February 2021, more than 405 million people have received a diagnosis of covid-19 and 5.8 million have died globally. Despite public health measures, vaccines, antiviral treatments, and monoclonal antibodies, covid-19 continues to overrun hospital wards and strain health systems. Clinical prediction models that help clinicians accurately identify those patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 at greatest risk of clinical deterioration may help to reduce morbidity and mortality.

In a linked paper, Kamran and colleagues (doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-068576) report on the development and validation of a novel, clinical deterioration prediction model for covid-19, the Michigan Critical Care Utilization and Risk Evaluation System (M-CURES). The authors used a statistical learning algorithm to narrow potentially predictive variables from the electronic health record to a parsimonious nine variable model-age, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, oxygen flow rate, pulse oximetry type (eg, intermittent, continuous), head-of-bed position, position of patient during blood pressure measurement (eg, standing, sitting, lying), venous blood gas pH, and partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood.

CURES automatically collected these variables from the electronic health record every four hours and dynamically recalculated the risk (through logistic regression) of a composite primary outcome of either in-hospital mortality or decompensation requiring heated high flow nasal cannula, intravenous vasopressors, or mechanical ventilation. The prediction model secondarily sought to identify patients at low risk of deterioration 48 hours after admission who could potentially be discharged early.

When internally validated among a cohort of 956 hospital admissions for covid-19 at the University of Michigan from 1 March 2020 to 28 February 2021, M-CURES had a c statistic (or area under the receiver operating characteristics curve) of 0.80 (95% confidence interval 0.77 to 0.84), indicating good discrimination.3 Impressively, the authors then worked with colleagues at 12 geographically distinct and demographically diverse medical centers across the US to externally validate their model in 8335 patients with covid-19. Here too, M-CURES showed good discrimination, with c statistics of 0.77 to 0.84, which were robust across time and subgroup analyses of age, sex, and race or ethnicity.

Although their prediction model was not prospectively evaluated, Kamran and colleagues estimated that it could identify 95% of patients with covid-19 at low risk of deterioration, potentially saving up to 7.8 bed days for each low risk patient. These results are comparable to those for the widely cited 4C deterioration model that uses 11 variables manually collected by the clinician on admission alone to identify hospital patients with covid-19 at risk of death or transfer to an intensive care unit; the c statistic for this model was 0.76 in both internal and external validations.

Kamran and colleagues’ analysis has limitations. First, we can only speculate on the real world effect of M-CURES in reducing mortality and transfers to intensive care. Although the model retrospectively predicted the primary outcome with a median lead time of 7-18 hours, it is unknown whether and how healthcare providers would act prospectively on alerts from the electronic health record, especially in the context of staffing shortages and alert fatigue.6 The true clinical benefit can only be ascertained from a randomized trial. Second, it is unclear why some of the model’s variables were selected, including pulse oximetry type, head-of-bed position, and venous rather than arterial blood gas pH. Third, although M-CURES’ algorithm is laudably open sourced, its use is limited to hospitals with the same proprietary electronic health record used in this study and to hospitals resource rich enough to employ bioinformaticians.

The most compelling contribution of this study is its model of a multicenter research collaboration for the rapid validation of a clinical prediction tool; it exemplifies the higher standard for research quality that a pandemic such as the covid-19 one demands. Nearly all clinical deterioration models published early in the pandemic were plagued by small, non-representative samples with risk for bias, limited or no external validation, and modest clinical value. Kamran and colleagues externally validated their prediction model at 12 hospitals without time consuming data sharing agreements that can discourage and delay external validation at several institutions. The authors did this by creating autonomous research teams who simultaneously employed common data dictionaries and data extraction approaches that, when paired with a plug-and-play machine learning algorithm, enabled not only external validation for M-CURES but also showed its durable discriminative capacity and calibration across time, geography, and patient populations.

As with transnational covid-19 clinical trials using adaptive designs that efficiently test multiple treatments in parallel, informatics efforts must find new ways to work together that leverage collective resources in the pursuit of common public health goals. Although creating such shared research infrastructure is labor intensive upfront, it prioritizes collaboration over competition in delivering robust, “living” clinical prediction models that can be recalibrated easily as new covid-19 variants and treatments emerge and lays the groundwork for prospective analyses evaluating the real world utility of prediction models such as M-CURES.

(6). Kamran F, et al. Early identification of patients admitted to hospital for covid-19 at risk of clinical deterioration: model development and multisite external validation study. BMJ 2022;376:e068576

Objective: To create and validate a simple and transferable machine learning model from electronic health record data to accurately predict clinical deterioration in patients with covid-19 across institutions, through use of a novel paradigm for model development and code sharing.

Design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: One US hospital during 2015-21 was used for model training and internal validation. External validation was conducted on patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 at 12 other US medical centers during 2020-21.

Participants: 33 119 adults (≥18 years) admitted to hospital with respiratory distress or covid-19.

Main outcome measures: An ensemble of linear models was trained on the development cohort to predict a composite outcome of clinical deterioration within the first five days of hospital admission, defined as in-hospital mortality or any of three treatments indicating severe illness: mechanical ventilation, heated high flow nasal cannula, or intravenous vasopressors. The model was based on nine clinical and personal characteristic variables selected from 2686 variables available in the electronic health record. Internal and external validation performance was measured using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) and the expected calibration error-the difference between predicted risk and actual risk. Potential bed day savings were estimated by calculating how many bed days hospitals could save per patient if low risk patients identified by the model were discharged early.

Results: 9291 covid-19 related hospital admissions at 13 medical centers were used for model validation, of which 1510 (16.3%) were related to the primary outcome. When the model was applied to the internal validation cohort, it achieved an AUROC of 0.80 (95% confidence interval 0.77 to 0.84) and an expected calibration error of 0.01 (95% confidence interval 0.00 to 0.02). Performance was consistent when validated in the 12 external medical centers (AUROC range 0.77-0.84), across subgroups of sex, age, race, and ethnicity (AUROC range 0.78-0.84), and across quarters (AUROC range 0.73-0.83). Using the model to triage low risk patients could potentially save up to 7.8 bed days per patient resulting from early discharge

Conclusion: A model to predict clinical deterioration was developed rapidly in response to the covid-19 pandemic at a single hospital, was applied externally without the sharing of data, and performed well across multiple medical centers, patient subgroups, and time periods, showing its potential as a tool for use in optimizing healthcare resources.

(7). Kearon C. Diagnosis of deep vein thrmbosis with D-dimer adjusted to clinical probability: prospective diagnostic management study. BMJ 2022;376:e067378

Objective: To evaluate the safety and efficiency of a diagnostic algorithm for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) that uses clinical pretest probability based D-dimer thresholds to exclude DVT.

Design: Prospective diagnostic management study.

Setting: University based emergency departments or outpatient clinics in Canada.

Participants: Patients with symptoms or signs of DVT.

Intervention: DVT was considered excluded without further testing by Wells low clinical pretest probability and D-dimer <1000 ng/mL or Wells moderate clinical pretest probability and D-dimer <500 ng/mL. All other patients had proximal ultrasound imaging. Repeat proximal ultrasonography was restricted to patients with initially negative ultrasonography, low or moderate clinical pretest probability, and D-dimer >3000 ng/mL or high clinical pretest probability and D-dimer >1500 ng/mL. If DVT was not diagnosed, patients did not receive anticoagulant treatment.

Main outcome measure: Symptomatic venous thromboembolism at three months.

Results: 1508 patients were enrolled and analysed, of whom 173 (11.5%) had DVT on scheduled diagnostic testing. Of the 1275 patients with no proximal DVT on scheduled testing who did not receive anticoagulant treatment, eight (0.6%, 95% confidence interval 0.3% to 1.2%) were found to have venous thromboembolism during follow-up. Compared with a traditional DVT testing strategy, this diagnostic approach reduced the need for ultrasonography from a mean of 1.36 scans/patient to 0.72 scans/patient (difference −0.64, 95% confidence interval −0.68 to −0.60), corresponding to a relative reduction of 47%.

Conclusions: The diagnostic strategy using a combination of clinical pretest probability and D-dimer identified a group of patients at low risk for DVT during follow-up while substantially reducing the need for ultrasound imaging.

(8). Giles C. Covid-19: For the clinically extremely vulnerable, life hasn’t returned to normal. BMJ 2022;376:o397

I spent last week hoping I had covid.

What started off as a scratchy throat developed into a stuffy nose, slight cough, and a general feeling of being unwell. “Could this be it?,” I wondered to myself as I did multiple lateral flow tests.

Odd though it may be, my thinking was that although I was ill, I wasn’t that ill. If this was covid, maybe I’d be okay. Of all the stresses over the past two years, the uncertainty about what covid may or may not do to me is one of the hardest to live with (note: it wasn’t covid). I have an immune deficiency which means I don’t effectively create the B cells which play an integral role in fighting off infection. It also means I don’t produce as good a response to vaccines as the average person. This means that despite dutifully having my four covid vaccinations, since March 2020 I’ve lived a weird kind of half-life, where I still remain vulnerable to a virus that others are increasingly forgetting about.

At first, I shielded religiously. I saw no one, but my husband and daughter, and I didn’t dare go inside anywhere other than my home. The government sent me-and 1.5 million people like me-somewhat terrifying letters and texts warning us that we were at extreme risk. But they also put into place useful programmes, such as the delivery of food parcels and medicines, and enabled shielders to claim statutory sick pay if they were unable to go to their usual place of work.

We all knew that this couldn’t go on forever-and who would want it to? But, since the start of the “great reopening” in the middle of 2021, it seems the government has conveniently forgotten about the 1.5 million vulnerable people they were so eager to protect back in early 2020. The shielding programme was paused in April 2021, then quietly dropped a few months later. The Department of Health and Social Care said that the clinically extremely vulnerable should follow the same advice as the rest of the population, but with some additional suggested precautions such as avoiding “enclosed crowded spaces.” And last week, Boris Johnson, UK prime minister, told us that the pandemic is essentially over-all restrictions will end very soon, including the need to self-isolate.

Except for the vulnerable, the pandemic isn’t over. Life hasn’t returned to normal, and what has been a difficult two years now appears to stretch ever further into the future with no real prospect of “normal” life anytime soon. The government’s message that “vaccinations are the best way to protect yourself” is hollow advice for people like us.

Clinically vulnerable people now have no legal right to work from home, or to request different roles if their job puts them at increased risk, or to claim statutory sick pay. Those of us with children face a daily game of covid roulette, sending our children into schools where the virus is rife and public health measures are often absent. Masks may still be mandatory on some forms of public transport, but compliance is waning and they soon won’t be required. Anti-vaccine rhetoric has reached fever pitch.

The sense of despair I feel as the world moves forward and I am slowly left behind is crushing. What is the point? I wonder late at night as government advice to continue to avoid “enclosed crowded spaces” means using public transport less, avoiding visits to offices and work events, and being unable to spontaneously participate in the taken-for-granted everyday pleasures of shopping, going to the cinema, or a restaurant.

The clinically vulnerable obviously can’t take to the streets in protest-surely one reason we don’t feature on television debates and in truck convoys is because of our aversion to crowds. I know I am not alone in my despair. Many friends and colleagues who live with cancer or other conditions have contacted me over the last year, asking how I keep my spirits up. The answer is that I haven’t. Friends ask whether I think they’re being paranoid if they avoid large gatherings-I don’t. But other than virtual hugs and supportive words between us, we face being left out of the best parts of life by a government and some parts of society who think we all just need to “get on with it.”

The clinically vulnerable obviously can’t take to the streets in protest-surely one reason we don’t feature on television debates and in truck convoys is because of our aversion to crowds. I know I am not alone in my despair. Many friends and colleagues who live with cancer or other conditions have contacted me over the last year, asking how I keep my spirits up. The answer is that I haven’t. Friends ask whether I think they’re being paranoid if they avoid large gatherings-I don’t. But other than virtual hugs and supportive words between us, we face being left out of the best parts of life by a government and some parts of society who think we all just need to “get on with it.”

When I think back to the early days of the pandemic and the fear and sadness I felt as we locked down, as friends and colleagues fell seriously ill and died, and as we clapped for the NHS, I was grateful for the scientists, doctors, key workers, vaccines, and research. We felt like a country connected, a nation united. Now, two years later, after all the pain, work, and sacrifice, it seems to me that maybe we are not all in this together after all.

(9). Richards T. The gift of death. BMJ 2022;376:o393

“I dreamed that I was dead last night. Then I woke up and found I was still here. It was such a disappointment.”

My 98-year-old mother surprised us with this comment, for she rarely talked about dying and death during her decline from advanced frailty, although she repeatedly said, “I never thought it would go on so long.”

Her final months were harrowing to witness. But how much harder must they have been to bear? It’s left me wondering if she, and we, her children, could have made any different decisions.

Ever well organised, she made end of life plans years before the event. These included listing who to bequeath her modest collection of precious things to, putting memorabilia in boxes that she thought her children and grandchildren would treasure, and choosing psalms, hymns, and music for her funeral. Her GP practice had her “Do not resuscitate” form. She had savings to pay for care.

Planning for death did not stop her enjoying life and enhancing the lives of others. She supported many elderly friends, most of whom she outlived. Observation of their final journeys made her dread losing her independence and “lingering on” with poor quality of life. “If I get like that,” she said, “you must take an axe to me.”

Assisted dying is one of the topics addressed in the report of the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death: Bringing Death Back Into Life.12 Its headline message is that over medicalised “Western death systems” are in need of radical reform. It points the way to a “realistic utopia,” where death is valued as a social and spiritual process, and families, communities, health and social care services care for the dying in partnership. The closest to the “ideal,” a model of care in Kerala in India, is described.3 Regarding death as a physiological event to be hidden away, and a failure of modern medicine, damages people, and health systems alike.

At a recent webinar to launch the Lancet commissions’ report, Raj Mani, an intensive care specialist in Yashoda Hospital, Ghaziabad, said that many people in India think high tech Western medicine is always the best form of care. As a result, too many people “die badly in intensive care units.” Their suffering is “amplified” and the cost impoverishes their families. The report makes the same observation about some deaths during the covid-19 pandemic, and recommends that health systems prioritise management of suffering (not just extending life) and for all health and social care professionals to be competent to care for the dying and the bereaved.

In high income countries around 10% of total healthcare expenditure is spent on the last year of life, and “excessive” care exerts a notable toll on the environment as well as individuals and their families, said Richard Smith, co-chair of the commission. He also emphasised the gaping global inequity in access to palliative care services and opioids.

My mother was fortunate to have both. The challenge was to make her passage to death as smooth as possible.

What counts as excessive treatment?

When she presented with symptoms and signs of aortic stenosis at 80, a doctor she saw told her “the good thing about this diagnosis is that when you die, you will die fast and won’t suffer.” Should she leave it at that? She asked us what we thought, listened to our varied views, and decided it was sensible to have a formal cardiac assessment. Tests revealed a critically tight stenosis and aortic valve replacement was recommended. She went ahead, and after a stormy postoperative course achieved a good quality of life.

Bilateral hip replacements followed. Then recurrent treatment for a combination of wet and dry macular degeneration. She bore the journey to near total blindness without complaint and systematically built a comprehensive support network which, stepped up over time, enabled her to live independently until she was 96.

Then grumbling abdominal symptoms reached a head. She was admitted to hospital with intestinal obstruction and found to have colon cancer. Aware this was a terminal diagnosis she asked about options and was given two. Move into the adjacent hospice to die or take a chance on colonic stenting. Risky, because of the site of the tumour, but if successful, should buy her a few more months.

She opted for the latter. My sister and I held her hands as she went down for the procedure exuding calm. She talked about having had a good innings, told the surgeon how grateful she was, and reassured him she fully understood the procedure may kill her. I suspect that was her wish.

It went well and she went to live in my brother and sister-in-laws lively household. Here a new community of support enabled her to find new things to enjoy. She did not complain about her deteriorating health and dutifully complied with her diet and treatment regimen.

Daily (aided) walks got shorter. She was pale and started to collapse. Anaemia due to bleeding from the cancer was suspected. Should a blood count be done? It was, and a blood transfusion rallied her for a bit. Her decline continued. Did covid vaccination make sense? Antibiotics for a chest infection? She had both.

Stairs became impossible. Weeks stretched to months over which her strength, memory, focus, and orientation ebbed away. She was tired, slept a lot, and stoically bore the indignity of needing help to use the commode, dress, and wash. Usually too tired to talk for long she still conjured bursts of sparkling exchange.

It was immeasurably sad to see her bed bound, increasingly deaf as well as blind, troubled by pain, oedematous hands and legs, sleeping badly, and experiencing loss of bowel control. Caring for her was physically, as well as emotionally, hard work and we sought the help of a live-in carer.

The arrival of a death doula, was transformative

A skilled South African carer came exuding warmth and good cheer. Looking after the dying “is my calling” she said, and I find it “hugely rewarding.” She got my mother talking about her past and singing songs. They said prayers together and seized the best moments of the day. She speedily recognised the redoubtable spirit within my mother’s pitifully wasted body and did not tip toe around dying and death.

A seasoned death doula, she accurately identified the day my mother would die and called the family to the bedside. After her death she opened the window to let her soul fly out. She bathed her and dressed her in clean clothes, with the same tenderness and respect she had always shown. The family found it harder to look death in the face. Happy to leave “practicalities” to the undertakers. Illustrating perhaps, one of the points made in the commission’s report, about the disappearance of old rituals which honour the body of the dead.

Avoiding overmedicalisation at the end of life is challenging. At what age and stage is best high tech care neither appropriate or affordable? And who gets to make the decision? More open public, as well as professional, discussion and debate are needed, informed by better understanding of people’s end of life experience, and what services and treatment they and those who care for them value. The opportunity costs of high healthcare spending in the last year of life are high and a balance to be struck between preferences of individuals and society as a whole.

My mother did not avoid dependency and did “linger on” longer than she wished. But caring for her at home brought the family together and thanks to her courage, patience, grace, and positivity there were happy times. I hope I can summon half of her resources when I’m dying-and secure the help of her death doula

(10). Sheather J. We need to remind ourselves of the impact of war on health. BMJ 2022;376:o499

The effects of war on health are both intimate and general. Health impacts are immediate-people are wounded and killed-and then the impacts ripple outwards, in space and time.

The repercussions echo through individual lives and, all too often, down the generations.

In the first minutes, hours, and days of a war, physical trauma is primary: individual human bodies are mutilated by the ferocity of modern munitions. Lives end or are changed forever.

For all the talk of “smart” weapons, and targeted attacks, the first onslaughts are seldom restricted to combatants. Recent conflicts, such those in the greater Middle East, have sucked huge numbers of citizens into the maelstrom, with devastating effect. Conflicts in Rwanda and Kosovo in the 1990s saw as much as 90 per cent of fatalities among civilians. It is difficult to comprehend the scale of slaughter unleashed by industrial and technological war: the 20th century saw an estimated 191 million conflict related deaths-approaching half the current population of Europe.

The health impacts of war do not stop with trauma from the fighting. Crude estimates suggest that for each person killed directly by war, nine will be killed indirectly-although much will depend upon the nature of the conflict and the underlying conditions for health in the countries in which it is fought.

War degrades environments. Recent conflicts in Syria and Yemen have seen the deliberate targeting of both built environments and the health services integral to them. The impact on health services and public health will likely be shattering, particularly if conflict spreads into urban areas. Civilian infrastructure is exquisitely vulnerable to modern conflict. With transport impeded, the flow of essential health goods interrupted, and health staff and patients unable to move, health outcomes, particularly and initially among pregnant women and young children, will rapidly deteriorate-we know that child and birth-related mortality are hit hard by armed conflict.

Without a rapid halt to hostilities, a cascade of longer term health problems will be released. Where civilian infrastructure, including access to fresh water, sanitation, and a stable food supply are disrupted, infectious diseases re-emerge.

Unsurprisingly, human behaviour changes during conflict and non-communicable diseases linked to riskier behaviour increase. The mental health impacts of the conflict are likely to be extreme.

As a war of invasion gets under way, the mental health effects will be serious and enduring. Those directly caught up in the conflict will be at immediate risk of post traumatic stress disorder, but depression, anxiety, and other stress-related conditions, including alcohol and drug misuse will also increase, and once again these may have life long and even inter-generational impacts.

As we know from recent conflicts, the health effects of war can be displaced far beyond the borders of the countries involved. Among the most significant global issues in health and human rights arises from the health needs of millions of people displaced by modern conflict. People leaving war zones take their trauma with them. They suffer appallingly on the migrant routes into the more stable parts of the world. They are prey to a range of infectious diseases, they struggle to find nutritious food and housing that can support health.

War destroys more than bodies and minds. It tears up the roots of human wellbeing, rips the fabric of human community, severs bonds between people and the places they inhabit. And it leaves an enduring legacy. War contaminates places of human habitation physically and psychologically. Traumatic memory can make the search for peace impossible. And without peace there can be no real hope of human health or flourishing.

An invasion is not just a tragedy for today’s generation. It will also lie heavily on the wellbeing of future generations.