Esophageal varices grade III: A case report

Ramudu1*, Dr. S. Vadivel Kumaran2, Vanitha3

1Nurse Educator, Kauvery Hospital, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India

2Consultant Medical Gastroenterology and Hepatologist, Kauvery Hospital, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India

3Staff Nurse, Kauvery Hospital, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India

*Correspondence : +91 9790861662; E-mail: nursingdirector.kch@kauveryhospital.com

Abstract

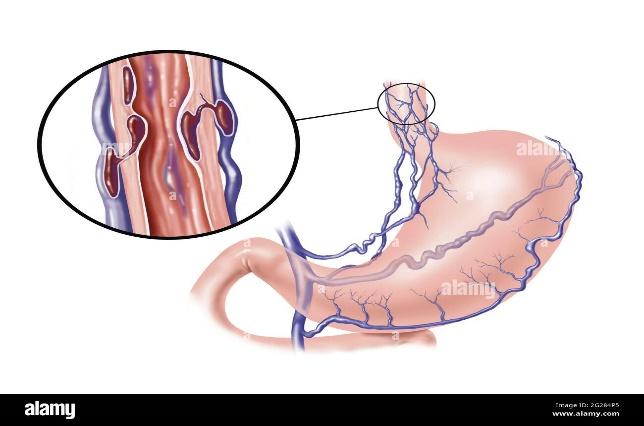

Veins that become enlarged in the esophagus are called esophageal varices. Those who are affected with severe liver disease are particularly prone to developing esophageal varices. Esophageal varices develop from Portal Hypertension, that arises from obstruction to normal portal vein flow from the alimentary (digestive) system, either by the scar tissue in the liver (ongoing cirrhosis) or a clot that blocks the regular blood flow (thrombosis in the portal vein) towards the liver. Portosystemic collateral pathways (also called varices) develop spontaneously via dilatation of pre-existing anastomoses between the portal and systemic venous systems. This facilitates shunting blood away from the liver into the systemic venous system in portal hypertension, as a means of reducing portal venous pressure. However, these are not sufficient for normalizing portal venous pressure. The main sites of portosystemic collateral pathways are gastric, esophageal, para-esophageal, perisplenic, retro gastric, retroperitoneal-paravertebral, paraumbilical, mesenteric and anal canal. They can leak or lead to life-threatening bleeding. Gastro-esophageal varices should be looked for if a patient with long-term liver diseases such as jaundice, ascites, or palmar erythema,

Keywords: Esophageal varices, severe liver disease, jaundice, ascites, palmar erythema.

Background

Liver cirrhosis is a chronic disease of the liver which leads to increased portal venous pressure and formation of esophageal varices. The development of esophageal varices has been reported previously in up to 80% of patients with liver cirrhosis. Esophageal varices are frequently associated with potentially fatal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The risk of bleeding increases with the severity of esophageal varices, highest with large varices. The mortality associated with bleeding varices is extremely high, between 20 and 35%, even with the best in-hospital care. There is also a high rate of recurrence of bleeding in up to 60% of the survivors. Early detection of esophageal varices and timely prophylactic treatment initiation can minimize the risk of variceal bleeding and associated mortality.

Fig. 1. Gastro-esophageal varices.

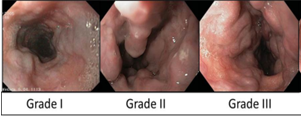

Grade of esophageal varices

- Grade 1: Small, straight esophageal varices.

- Grade 2: Enlarged, tortuous esophageal varices occupying less than one-third of the lumen.

- Grade 3: Large, coil-shaped esophageal varices occupying more than one-third of the lumen.

Case Presentation

A 57-year-old man, with a history of recent hospitalization with melena & hematemesis, and who underwent endoscopy and was treated conservatively at another hospital, was admitted to Kauvery hospital for further management. On arrival, he was conscious, oriented and afebrile. Melena was present (tarry stool).

He had pale conjunctiva.

Clinical assessment:

| Temperature | Pulse | Respiration | Blood pressure | SpO2 |

| 98.4 °F | 89 b/min | 20 b/min | 110/70 mmHg | 99% |

On physical examination, the patient was conscious.

Management

Necessary investigations were done. He had low Hb levels.

After anesthetic clearance, informed consent was taken. After adequate hemodynamic resuscitation, with fluids and packed red blood cell (PRBC), patient underwent endoscopy which showed large fundal varix with deep ulceration. Cyanoacrylate glue was injected into the varix above the bleeding site, and esophageal varix grade III was seen.

Esophageal banding – 5 elastic bands were deployed by suctioning into the varix starting from OG junction. After the procedure, patient was stable. One unit of PRBC was transfused.

Drug chart

| S.No | Drug name | Dosage | Frequency | Route |

| 1 | Tab. Inderal (Propranolol) | 20 mg | BD | Oral |

| 2 | Tab. Rifagut (Rifaximin) | 400 mg | BD | Oral |

| 3 | Tab. Pruvict (Prucalopride) | 1 mg | OD | Oral |

| 4 | Tab. Rabeloc RD (Rabeprazole) | 20 mg | BD | Oral |

Nursing care

Ongoing assessment

- Assessed for ecchymosis, epistaxis, petechiae, and bleeding gums.

- Monitored level of consciousness, vital signs, and urinary output to evaluate fluid balance.

- Monitored the client during blood transfusion administration if prescribed.

Provided nursing intervention for the client undergoing a prescribed iced saline lavage

- Ensured nasogastric tube patency to prevent aspiration.

- Observed gastric aspirate for evidence of bleeding.

- Protected the client from chilling.

After injection sclerotherapy, assessed for

- Aspiration

- Esophageal perforation

- Continued bleeding

Emergency Management

- Once esophageal varices rupture and begin to haemorrhage, it becomes an emergent situation requiring immediate care.

- Rupture of esophageal varices requires the following interventions:

- Maintain an open airway, position the patient to enhance breathing and expulsion of gastric contents that may be blood, and suction excess secretions and blood.

- Assess the rate and volume of bleeding. Assess blood pressure and pulse, with the patient in the supine position as well as in the sitting position( which indicate volume of possible blood loss

- Insert an IV access and administer fluids and blood products, rapid infusion of 5% dextrose, and a colloid solution until blood pressure is restored and urine output is adequate.

- Obtain a blood specimen for haemoglobin, haematocrit, PT, PTT, platelets, type and cross-match, electrolytes, and renal and liver function tests.

Hospital Discharge Criteria

The bleeding has stopped, stabilized blood circulation, and develop an appropriate plan for the treatment of comorbidities.

Outcome and follow up

The patient remained stable for a week and was discharged afterwards. He had no rebleeding and is currently abstemic for 2 months

Discussion

Esophageal varices are prevalent among patients diagnosed with liver cirrhosis. Presence of large varices indicate risk of bleeding. It is of paramount importance to do endoscopy on patients who are newly diagnosed with liver cirrhosis. Although a large proportion of patients may not have varices at diagnosis of cirrhosis, the predictors identified in this study could significantly augment the selection and prioritization of patients who might need immediate scoping. Patients with increased age, increased portal vein diameter, increased splenic diameter, ascites and advanced liver disease by Child-Pugh score are more likely to have esophageal varices and thus can benefit from prioritized endoscopic examination and appropriated primary prophylaxis.

Conclusion

Endoscopic variceal ligation is highly effective in obliterating esophageal varices in all age groups. The use of a multibander device for endoscopic variceal ligation is technically feasible and safe even in small children, and its use results in more rapid ablation of esophageal varices.

References

- Zhao W, et al. Application of shear wave elastography as a diagnostic method for esophageal varices. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10(2):1342-1350.

- Laine L. Interventions for primary prevention of esophageal variceal bleeding. hepatology. 2019;69(4):1382-1384.

- Han JH, et al. Rescue endoscopic band ligation of iatrogenic gastric perforations following failed endoclip closure. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:955-959.

Ms. Ramudu,

Nurse Educator

Dr. S. Vadivel Kumaran,

Consultant Medical Gastroenterology & Hepatologist

Ms. Vanitha,

Nursing Incharge