Dr Suresh Venkita, our Group Medical Director, a senior cardiologist and an avid writer, has yet again shared this lovely story from his desk.

Across the door and into the sky

I observed him carefully as he walked to the door. I knew that time was running out for him but suppressed the urge to check my watch. To relieve my tension, I took a deep breath and started counting in reverse under my breath. “Ten, nine, eight, seven…

His steps toward the door were hesitant and heavy, very slow and awkward, the acute awareness of which always made him make way for others first and then follow. Other travellers had already gone past him some time earlier. He was late, which made me anxious. I whispered “Son, walk along safely, it is time for your take off, to your long awaited galactic voyage. I shall be flying with you, in spirit, all the way ’’. I was watching him, through CC TV, shuffling out of the departure lounge at the Virgin Galactic space-drome, Mojave, California.

My son was born 25 years earlier and, when placed on my hands, seemed perfect to my eyes, which are those of a trained physician. The baby was born apparently unharmed by the prolonged labour fatal complications of which claimed the life of my wife in a civil hospital of a non descript town in the North East of India on the outskirts of which the air force station I worked in was located. But as the days went by I instinctively knew he too was harmed during that birth and as weeks and months went by it was clear that he was developing cerebral palsy.

Medical knowledge can be a crushing burden, it imparts you over time the intuitive knowledge to look into the crystal ball of life and see the medical future of those who come into your life. So I knew the course my son’s life would take. The disability, which is spasticity, will set in gradually, progress inexorably, peak eventually and finally abate and arrest, leaving my son with its lasting imprint and impact that he has to live with for the rest of his life.

I also knew that ‘Normality’ will disappear from our lives forever. We, father and son, would never hike, jog, cycle or climb mountains together, or go swimming and fishing in lakes and rivers or surfing on seas. We would never play across a tennis court or ‘basket’ or ‘foot’ our ball. Probably he would never drive. We may not be even able to fly a kite together so I dared not dream that we will ever fly together.

But one look at his bright, inquisitive and intelligent eyes reassured me that he would not let such physical limitation restrict his exploration and enjoyment of this world and what lies beyond its boundaries.

I resolved that I would be there for him, for as long as I can, to assist him to face this harsh, demanding and uncertain world, often unfeeling and unfair to the handicapped.

Instantly I became both his mother and father. That was not easy but the medical training, and knowledge of nursing, that a military doctor acquires as a part of training came handy. I was adamant that I will not share that responsibility and commitment. Though I had domestic staff to relieve me for a while when I had to be away at work I was particular about being the prima donna, the prevailing governess, to my child!

I became adept at feeding, changing nappies, bathing, dressing and rocking my son to sleep. He was uncomplaining as I sang lullabies to him the verses of which were mostly made up impromptu by me and delivered thoroughly off key. He did not howl when I antiseptically cleared his blocked nose during nasty colds and was very brave when I imposed the entire regimen of vaccination on him, during which his eyes would fill with tears but not a whimper would escape his lips.

I became good at entertaining him. I pushed him in his pram to, and played with him, in the children’s park and I thought he was puzzled that his dad did not look like other moms! I talked to him incessantly, like a grand mom, and he gurgled in response. We became great at communicating, and even developed a language of our own!

There were days, and nights, when he would get very sick and feverish. I walked all night comforting him. I felt privileged to be his father and confident about taking care of him during such trying and troubled times. I could also sense his unshakable trust and belief in his all too fallible father which made me feel good; there wasn’t anything else in my life to feel good about except my skill in taking care of my patients.

I was posted to an air force station that taught cadets how to fly. I had a fascination for flying which made me jump into any cockpit that had a place for me and I could feel some of that rubbing off on my son. Our sky was always either full of birds or tiny aeroplanes darting about during the day and with the stars twinkling at night, and we watched both with endless curiosity and concentration. I often talked to him, though he was only a little baby. I told him that the motto of my employer, the Indian Air Force, which was adapted from the verses of John Gillespie Magie Jr, a poet-flyer, was ‘”Slipping the surly bonds of earth and touching the sky with glory’. I believe the actual verse ended in ‘touching the face of god’ but I suppose that was a tall order for both the plane and its flyer. But I thought my son would find it easy to do so, if he were the flyer; gods are said to greatly love children they choose to burden with disabilities, as they come to be considered as ‘special children’.

Such children belonged to the stars; we both became adept in identifying them and the patterns they weave magically across the sky to mesmerize us each night.

From our home on the fringe of the airfield, we could see the aircrafts taxi out to the runway and climb elegantly and effortlessly into the air, their adopted home. But the birds were different; they belonged in the sky which was their element. Some circled almost lazily all day but many were focused flyers and flew in well defined formations, heading with determination to some distant destination. We thought the birds and planes were quite similar that way and probably observed each other and learnt all the time from each other.

I thought time was ripe to introduce him to Richard Bach.

Bach’s ‘Jonathan Livingston Seagull’, the soaring story of a sea gull who wanted to be a better flyer, amused and fascinated him. Being so severely limited in his own range and dexterity of movements he could readily empathize with the gawky, squat and ungainly sea gull, acutely aware of its awkwardness compared to other agile birds in the sky, yet determined to go on striving, and never give up, in learning how to fly better, longer and higher.

But he could not emulate the intrepid sea gull. Cerebral Palsy restricted him every moment of his life. His life was like that of Jean- Dominique Bauby who developed the ‘Locked in Syndrome’, described with such haunting pain, in ‘The Diving Bell and the Butterfly’. Jean’s body was restricted in all movements as though inside a rigid diving bell, confined, clumsy and claustrophobic, but the mind was ‘libre’, free to be like the evanescent and ethereal butterfly that could escape the diving bell and explore the world, both real and imaginary.

Nothing held my son back from inquiry and industry. He quickly graduated to dealing with, dissecting and designing model aeroplanes. His hands holding the remote control, though stiff, distorted and ungainly, could manipulate the plane to engage in every mode of flight. The control column or ‘stick’, of a real plane was more challenging to manipulate but he was determined to try to fly them. He attempted gliders first as gliding was so elemental, in equation and equilibrium with the air and the skies, and invited you to dance with the thermals that invited you to soar higher and higher. We flew together; to certain extent he could use his limited loco motor skills to guide the glider but they were clearly inadequate and unsafe to steer a powered flight.

Yet we flew in them to his heart’s content, intimate and exploratory flights in Cessnas and Pipers, the work horses of personal flights.

Every time he was ready for takeoff, he would turn to me, look me in the eyes and place his right palm over his heart, that was his way of saying ’Love you, Dad’.

Soon his mind took a quantum leap into exploration of space. His extensive reading and insatiable curiosity took him flying with the Sputniks, orbiting with Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space, various unmanned and manned flights in orbits around the moon and finally Apollo 11 to the moon and back. He graduated onto study of the space shuttles. His mind travelled with the Soyuz rockets to the ISS (International Space Station) and with the satellites that explored the galaxy and beyond, studying Mars, Jupiter, Pluto and the rings of Saturn.

As my child came to terms with his physical restrictions by his intellectual forays into the stratosphere and outer space my career took us across oceans and continents to some of most unusual parts of the world. Together we explored landscapes, cultures, languages, food, flora and fauna. It was during that perambulation that we met the visionary man who envisaged the spacedrome in the Mojave Desert and the opportunity for galactic travel.

When we first heard about it, our eyes locked and we knew instantly that he should be on its maiden voyage, not only as a tribute to that man, his vision and mission but also to celebrate our life and times together, of which aviation was an integral part. I have had my fling with flight, now it was Junior’s turn to ‘slip away from the surly bonds of earth and touch the outer space with glory’.

A 40 year long career as a roving cardiologist to the world had left with me a kitty that could afford the six figure fee for the flight. I was happy to upturn that kitty and fish for the last dollar that would enable my boy to be on that flight to the stars.

There was also one deeply personal and absolutely compelling reason for that decision. That dark and devastating secret was held close to my heavy heart. I had come to know just the previous week that my son’s brilliant, radiant, intuitive and intelligent mind from which had sprouted many insights that warmed my heart and fired my mind had also spawned one the fastest growing brain tumours known to medical science- a high grade anaplastic Oligodendroglioma. I was hoping that the rigorous medical examination that preceded selection of travellers will not pick it up and disqualify him. I was also afraid that soon after his return the tumour would erupt in one swift, searing and soaring inferno that would consume my precious and precocious son.

The day finally dawned for his flight. He, along with other passengers, prepared for the flight and donned the heavy gear for the space travel. I watched him on CCTV as he struggled with the space suit that challenged his limited flexibility. I watched proudly as he was charming, pleasant, courteous and affable with every other passenger, making way for them and even assisting some of them to leave for the flight. Eventually all had left, it was his turn and it was time to catch up with the rest. He got up with great effort, walked with even more, turned, waved, smiled at me and placed his right palm over his heart. In that one moment every moment of our life together flashed before my eyes; my heart welled up with ache and filled my eyes with tears. I could see him no more.

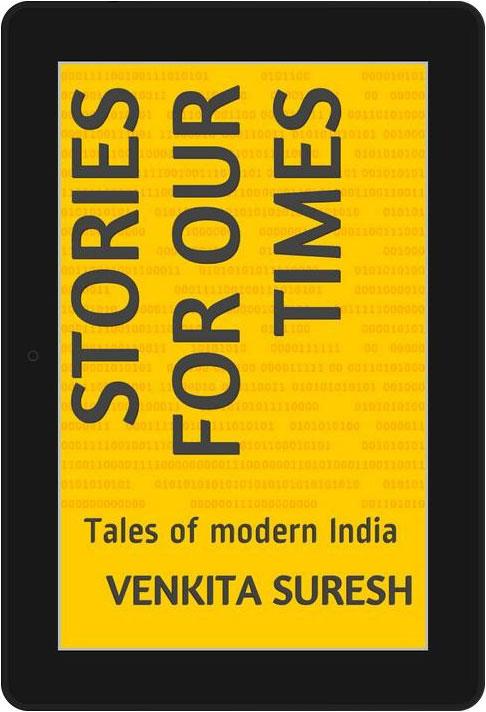

Article by Dr. Venkita. S. Suresh

Group Medical Director

Kauvery Hospital